Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

The Three Amigos

By Kent Taylor

Unless you were a Yamaha fan, bleeding bumblebee black and yellow, the late 1970s were a bleak time for motocross enthusiasts. Team Yamaha racers were winning all of the major championships in both the U.S.A. and Europe, and second place was often not even close. In 1978, Bob “Hurricane” Hannah snagged every title he could wrap his gloves around, with series titles in those hands before the last events had even been run. Dynasties can be good for sport, but it often seemed as if Hurricane season was going to last forever.

The storms carried over into 1979, and the new year looked to be much like the old year as Hannah began to dominate both the Supercross and National Championship series. And it would have likely been another race for second place, but for a couple of MX veterans who weren’t quite ready to roll over and play dead.

Both Marty Tripes and Kent Howerton had established themselves as MX stars on the AMA circuit long before anyone outside of Southern California had even heard of Bob Hannah. Howerton had won the 1976 AMA 500cc National Championship, while Tripes had scored two consecutive wins at the event formerly known as the Superbowl of Motocross. But by 1977, Hannah had been crowned as the new king of the hill, and it was going to take a mean motor scooter and a bad go-getter to knock him off.

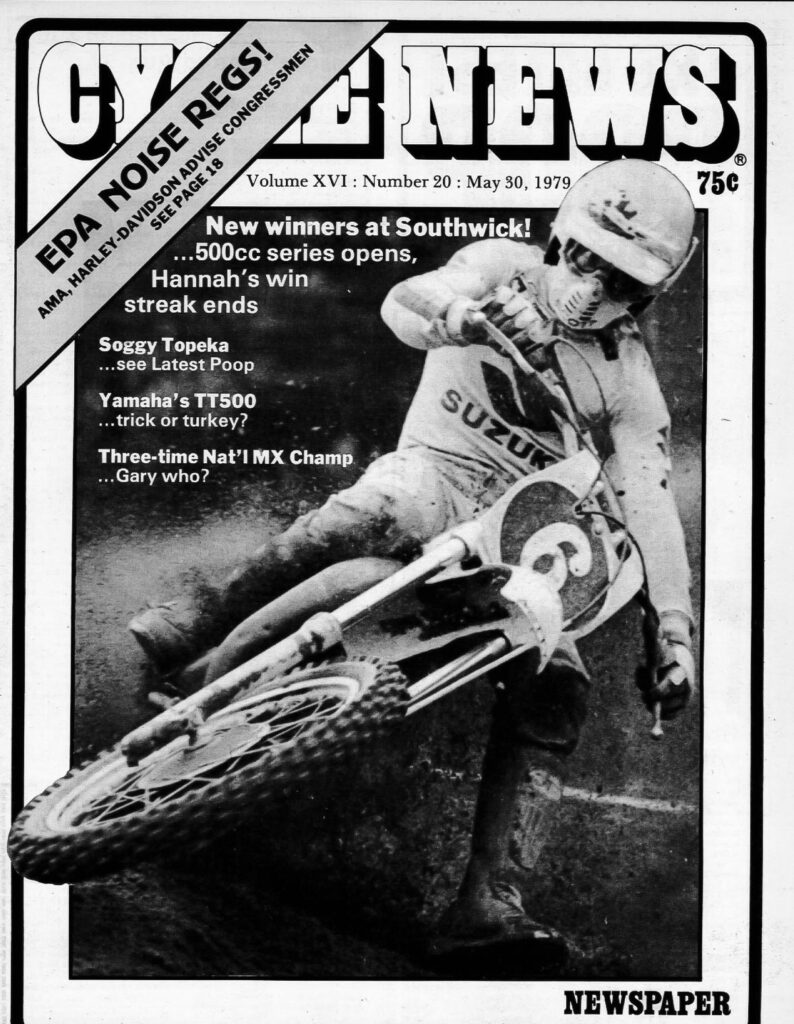

It would be impossible to describe Kent Howerton as either mean or bad, as the “Rhinestone Cowboy” was one of the nicest guys in the sport. But the Team Suzuki star became the first rider to stop the Hannah/Yamaha train when he snagged the overall win at the Southwick, Massachusetts round of the 250cc AMA National Championship series. Howerton had battled Hannah hard in the first moto before taking the win. How did he crack the code?

“I had never really trained until then,” he would say, years later, in the motocross documentary BackTrack. He started running, and “it almost made me sick, and I wanted to quit. But I kept going, and pretty soon, I found I could ride as fast as he could, all moto long. And I started beating him.”

Howerton closed the gap in the points that day, and it looked as if the series would become a two-man battle. And then a third rider joined the fray.

When it comes to tossing around the “ifs and buts” of motocross history, it is difficult not to talk about Marty Tripes, one of the most talented racers ever to throw a leg over a motocross bike. Tripes displayed the kind of skill that made racing almost look easy and while he was often fast enough to run with the world’s best, he was just as often as unpredictable as a Midwestern winter.

“When Marty didn’t have any money in his pocket,” said a former ‘70s MX team manager, “he was like this,” lifting up his throttle hand in a mock, wide-open position. “But when he had that money,” the old race boss sighs and that same hand twists in the opposite direction, throttle closed. Game on, game off and then, without warning, game on again. Winston Churchill, once described Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The same analogy could be used to explain the talented MX’er named Marty Tripes.

Tripes had spent the first several years of his career bouncing from one marque to the next so frequently that it would be easier to name the few brands that didn’t employ the slightly pudgy Californian. Many rides, many wins—zero championships.

Something wasn’t clicking for Tripes—and it continued to misfire late in his career. The 1979 outdoor season got off to a rocky beginning for both Tripes and Team Honda. After the opening National at the Sacramento ORV Park, Tripes’ works Honda was claimed by a privateer racer. The AMA’s controversial claiming rule had been in effect for several years, but this was the first time a racer had successfully taken possession of a genuine, one-of-a kind works’ motocross bike. A privateer racer drove away with the hand-built Honda, and the hours that Marty and mechanic Jon Rosentiel had poured into testing and adjustment were now as worthless as sand in the bottom of an hourglass.

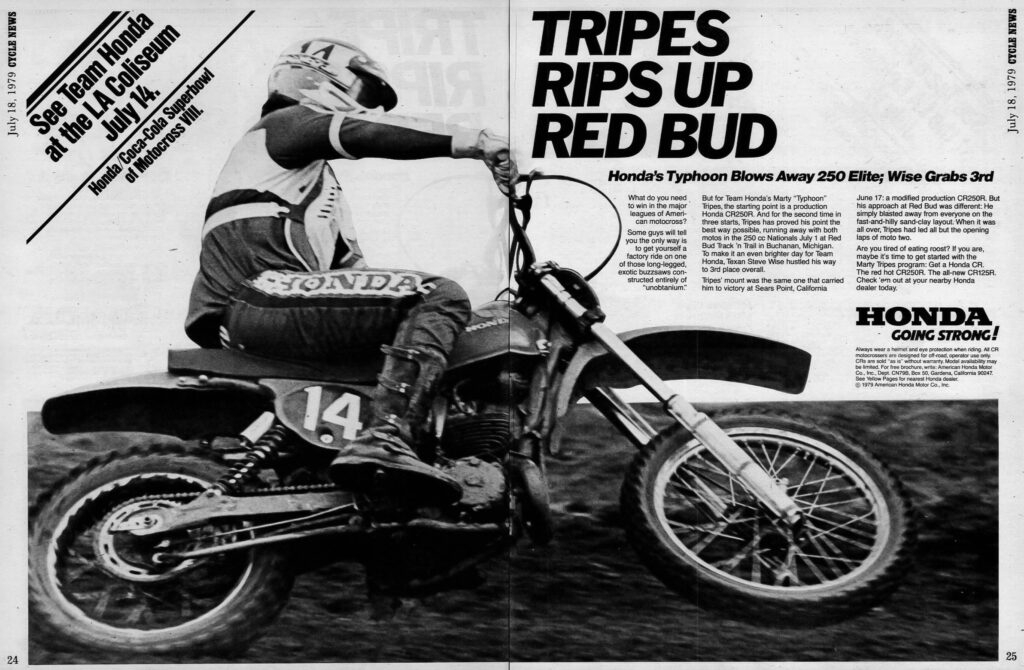

But true to his reputation as a racer who could be competitive on almost any motorcycle, Tripes, on his new bike, was also on the gas by mid-season. In June, he came out on top of a fierce, four-way battle at Sears Point, topping Hannah, Howerton and Jim Weinert for a double moto victory.

“I haven’t had to push that hard in a long time,” Tripes said afterward. It was a clash of America’s MX titans and Tripes’ win was Honda’s first major victory of the season.

But just one week later, when the AMA National Championship series moved to Lakewood, Colorado, the “riddle” returned. In the second moto, Tripes’ held a sizable lead, with Hannah in tow. At the halfway point, suddenly and inexplicably, he slowed his Honda to “a snail’s pace.” A likely bewildered Hannah moved past quickly to take the lead and the win. Tripes “allowed himself to coast back to fourth position.”

Money in his pocket?

Honda team manager Gunnar Lindstrom was upfront with the Cycle News staff with his criticism of his rider. “He doesn’t like the bikes,” Lindstrom moaned. “He doesn’t think he can keep up with the other riders. He knew he was going to get passed, so he pulled over.”

One week later, the predictably unpredictable Tripes stormed back to take another double moto sweep over Hannah at RedBud, Michigan. He even took a post-race swipe at his rival, saying, “I don’t even remember passing Hannah; it happened so fast. I could’ve gone faster!”

Hannah went on to win the 1979 250cc Championship, which would be his last major AMA title. Howerton’s best years were still ahead of him, as he succeeded Hannah as champ in 1980 and defended his crown in 1981. For Marty Tripes, the RedBud National would be his last AMA win. An unquestionable talent with unmatched skill, he remains an unsolved motocross riddle. CN

Click here to read the Archives Column in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Subscribe to nearly 50 years of Cycle News Archive issues