| September 29, 2024

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

Norton wins race and comparison in the same week.

By Kent Taylor

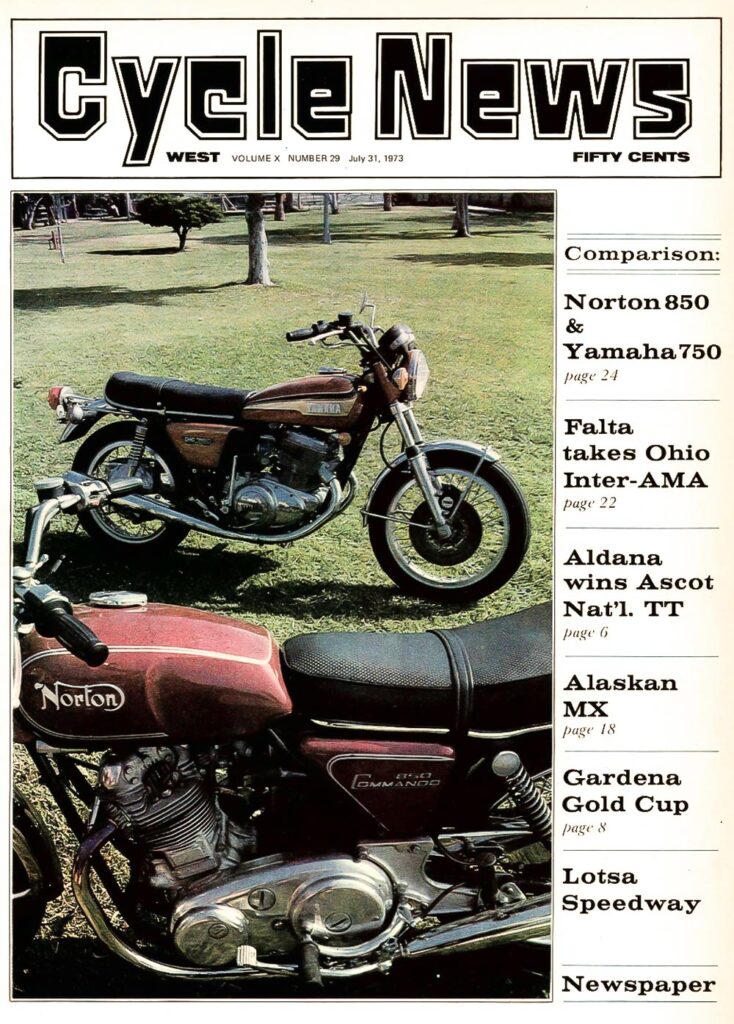

Norton-Villiers employees must’ve beamed with British pride and ordered another pint at the Slaughtered Lamb pub when the lead cooled and the Linotype machine spit out the July 31, 1973, issue of Cycle News.

More than 50 years ago, we compared a Yamaha 750 to a Norton 850. Fun—the Norton—won out over practicality.

More than 50 years ago, we compared a Yamaha 750 to a Norton 850. Fun—the Norton—won out over practicality.

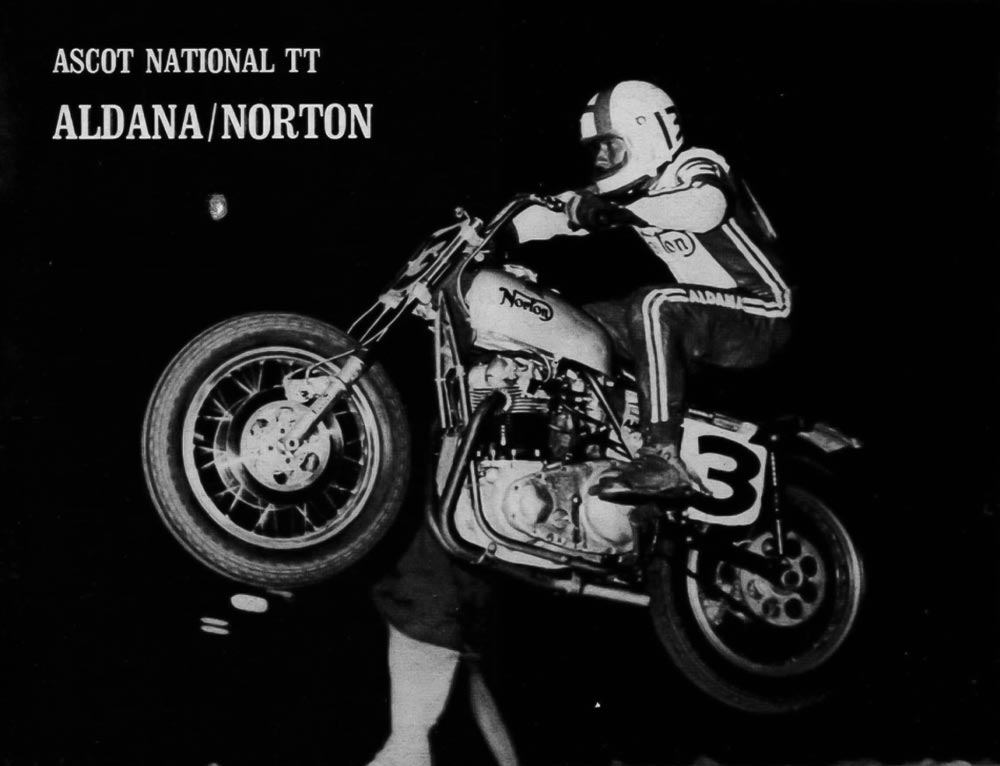

On page six, there was news that Norton-mounted David Aldana had powered to a big win at the Ascot TT round of the AMA’s Grand National Championship. Aldana’s victory came less than 24 hours after he had won the Gardena Cup, a half-mile race held at the same facility. Though the Cup race was a non-National, the race results read like a list of who’s who in AMA Flat Track, with John Hateley, Gene Romero, Mert Lawwill being just a few of the names who took part in the event.

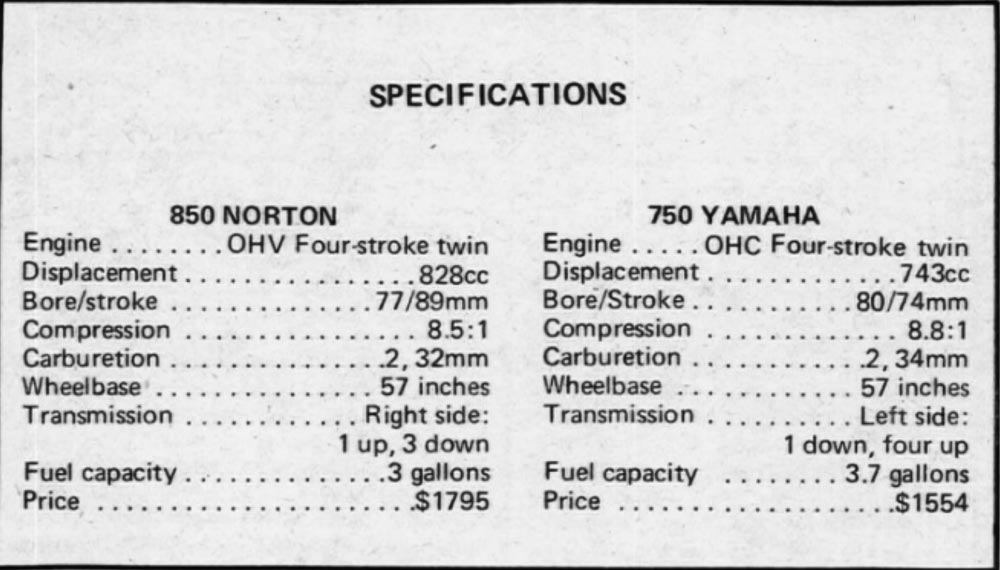

If Aldana’s victory wasn’t enough to mollify the Norton folks, then all they needed to do was to flip to page 24, where the “new” Norton Commando 850 (100cc more than the 750 version that it replaced) was going head-to-head with another machine that really was totally new. It would be the Norton 850 versus the Yamaha TX 750. “Which is better,” asked the Cycle News staff. “Tradition or progress?”

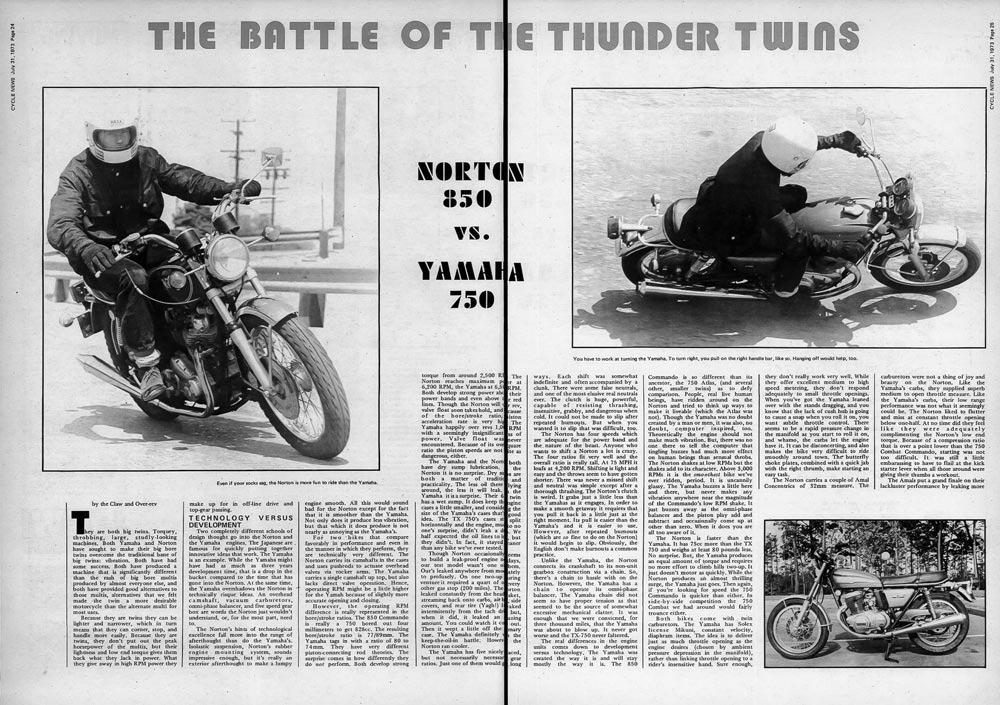

“They are both big twins,” said the CN staff. “Torquey, throbbing, large, study-looking machines.” In 1973, a twin-cylinder motorcycle was certainly no big deal. Both Honda and Suzuki had more cylinders, (four cylinders, four-strokes for the former, three cylinders and two-strokes for the latter). However, the king of the hill was Kawasaki’s new Z1 900, the bike everybody was talking about. The Z1 made a grand entrance with great fanfare for the common man. Another twin from Yamaha and a punched-out Norton Commando? Cue the golf clap.

In the same issue, Dave Aldana won on a Norton at the Ascot National TT. It was a very good issue for the Brits.

In the same issue, Dave Aldana won on a Norton at the Ascot National TT. It was a very good issue for the Brits.

But these twins still had some sex appeal; what they did, they did right. “Because they are twins, they can be lighter and narrower, which in turn means that they can corner, stop, and handle more easily,” wrote CN. “What they give away in high rpm power, they make up for in off-line drive and top gear passing.” These twins lacked the peak horsepower of their competitors, but Cycle News felt “their lightness and low-end torque give them back what they lack in power.”

The two motorcycles were rolling ideologies, each representing their country’s traditions and ambitions. The Yamaha spent three years living only on drawing boards and in prototype versions, with the Japanese engineers perfecting its overhead camshaft, vacuum carbs, and something called an omni-phase balancer (which ultimately proved itself to be anything but perfect). “Superior Japanese manufacturing technique” was indeed a phrase on its way to becoming a burr in the saddle for engineers in every country that wasn’t named Japan. Still, it was nonetheless something that appeared to be generally true.

The Norton? This motorcycle had made its name by carving up twisties throughout both Europe and the USA. Those names had changed over the years. They were known by Manx, Atlas and Commando, but they were still Nortons and they carried their reputation as powerful, fine-handling machines.

After losing the comparison, the XT 750 soon vanished from Yamaha’s lineup.

After losing the comparison, the XT 750 soon vanished from Yamaha’s lineup.

Timeless motorcycles. Unfortunately, they were also machines whose time had apparently been yesterday. The new Commando looked a great deal like its brethren from the ’60s, and the company’s “new and improved” bike featured little that was revolutionary. The famed Isolastic suspension was a fancy name for inserting rubber pieces into the engine mounting system. It “sounds impressive enough,” said Cycle News, “but it’s really an exterior afterthought to make a lumpy engine smooth.” Nevertheless, the Norton produced less vibration than the Yamaha, so score one for the Brits.

One of the most telling of all graphs in the story dealt with the tale of oil-leaking British motorcycles, of which the Norton 850 was one. “Ours leaked anywhere from moderately to profusely,” Cycle News wrote. “On one two-up touring venture, it required a quart of oil every other gas stop (200 miles). The Norton leaked constantly from the head gasket, streaming back onto carbs, air box, side covers, and rear tire. You could watch it come out.”

The Yamaha was dry. Dry as a Montgomery Martini. Dry as the high desert. The oil poured into the engine case filling hole stayed there. These sentences, in a nutshell, explain why the British motorcycle industry went bloody belly-up in the ’70s.

The staff proceeds to fire off the many differences between the two machines. The TX 750 has five speeds. The Norton shifts through its four gears, and it does so on the right side of the motorcycle. The Yamaha has Mikuni carbs, the Norton sticking to it Amals. The Norton required three kicks before it started. Pushing a button would bring the Yamaha to life.

The Norton wins the test, by the way, and it does so simply because the test crew was likely a group of hard-core motorcyclists. The Yamaha was more reliable, had better electrics, was more comfortable and performed well in nearly all the categories. But the Norton was “more plain fun to ride,” and at the end of the day, provided that you aren’t calling for a tow truck, riding is all about having fun. The Norton “turns easily…when a corner comes up, it just lays over and goes where you point it.”

The TX 750 not only fell to Norton in this test, but it would go on to have a miserable and short existence in Yamaha’s lineup. The TX was plagued with an unusual issue of frothing its own engine oil, with the aforementioned omni phase balancer being the culprit here. Yamaha dispatched scores of techs to fix the issue and while the 1974 model reflected the necessary repairs, the damage had been done. Nobody wanted this motorcycle, and it disappeared from the lineup.

On the dirt at the Ascot TT, it was Aldana over Roberts, Norton over Yamaha. On the road, the Commando topped the TX 750. Final score: Tradition 2, Progress 0. Lift another pint for the lads from Wolverhampton!CN