| May 19, 2024

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

Just Like Gaston’s

By Kent Taylor

In the motocross world today, a 125cc MX bike is like a feral cat; it has no home, nobody really knows what to do with it, and if you don’t know what you’re doing, it might hurt you. On the professional scene, 250cc four-strokes became the new 125cc two-strokes. Two-stroke stalwarts are welcome to compete in the class, and some take on the challenge, likely invoking the blessing of St. Jude Thaddeus, the patron saint of lost causes. Sadly, the little tiddlers just can’t compete with the more powerful four-stroke 250s.

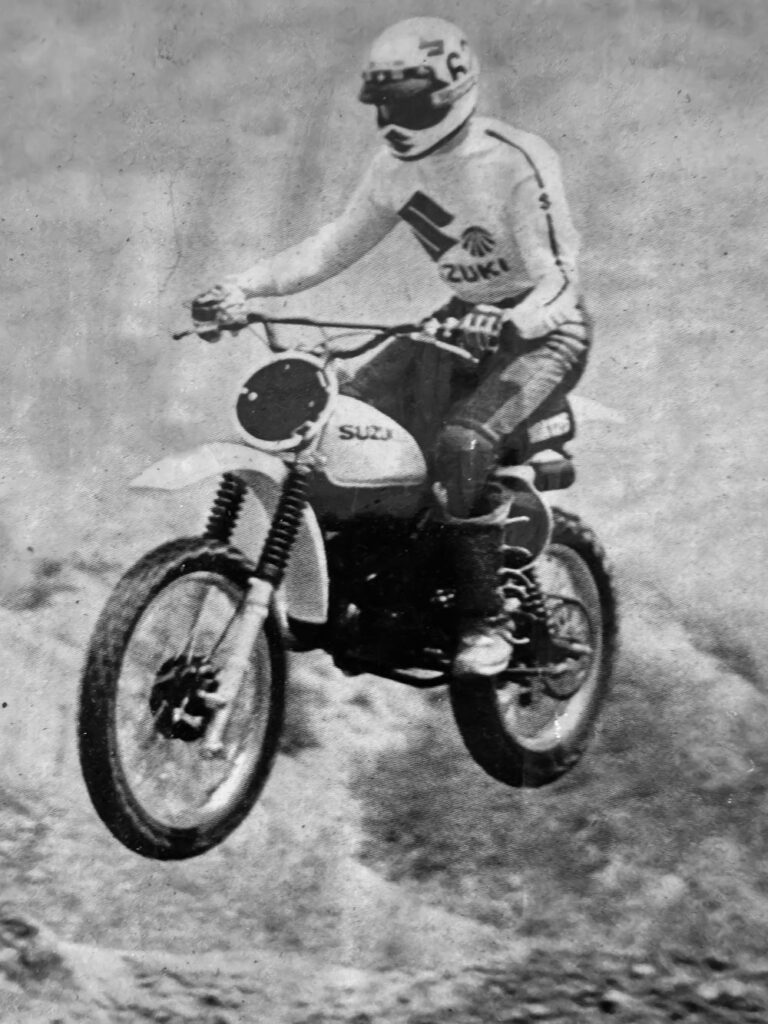

In 1976, Suzuki introduced the RM125A, which was a huge improvement over Suzuki’s previous 125cc MX model but wasn’t perfect. The 1977 RM125B (pictured) fixed all the faults of the A model and turned out to be a marvelous motocrosser.

In 1976, Suzuki introduced the RM125A, which was a huge improvement over Suzuki’s previous 125cc MX model but wasn’t perfect. The 1977 RM125B (pictured) fixed all the faults of the A model and turned out to be a marvelous motocrosser.

But not so long ago, it was once the most popular motorcycle at tracks, both national and local. They endured more abuse than a rental car: pistons pumping at 10,000 revolutions per minute, gearboxes snicking hundreds of upshifts and downshifts on every lap with the rider playing the clutch like a bow on a violin. Ridden properly, a 125cc motocross bike sounded like Barry Gibb with his finger in a wringer. The market for 125cc two-strokes was fiercely competitive, but ask those who know, and they will tell you the best 125cc MXer ever was the 1977 Suzuki RM125B.

Cycle News put the ’77 Suzuki through a wringer of its own in the January 26, 1977 issue. Three years earlier, Suzuki’s 125, then known as a TM model, would’ve been near the back of the pack in any comparison test of production machines. But by the time Jimmy Carter took over the White House, the yellow zonker was the cock of the walk!

Conversely, the Honda Elsinore, which had been the top 125 of 1974, was now considered an also-ran in a comparison test of the smaller bikes! Last year’s bike was a relic in the world of 1970s motocross and this was not a time for any manufacturer to rest on their laurels.

CN testers announced up front that the new RM had “…on paper, more of everything. More torque, more peak horsepower, more suspension travel, more trick stuff, and more weight. It also costs more dollars—$1025—but in the case of the Suzuki you can see exactly what made it cost more and why.”

The “more” in the engine department came with a slightly longer (4mm) stroke and other changes to the porting scheme. A lighter piston, heavier crank wheels, a “new, fatter expansion chamber,” and “a redesigned reed-valve” helped the RM deliver 22 horsepower.

In the suspension department, Suzuki borrowed technology from their own works’ bikes, giving everyday motocross Joe a chance to make believe they were Gaston Rahier, Suzuki’s 125cc World Champion. Long travel, spring air forks up front and “remote reservoir nitrogen-fluid Kayaba” rear shocks helped the Suzuki soak up the bumps and lumps found on ’70s racetracks. A rough track in the old days didn’t boast of the kind of cavernous holes and deep ruts that bring racers close to the Earth’s lithosphere in today’s MX, but they were still mighty rough in their own right and CN’s staffers said, “the gnarlier and the nastier the course is, the better this RM 125 will shine. It eats up whoop-de-doos and bumps that should be bone-jarring.”

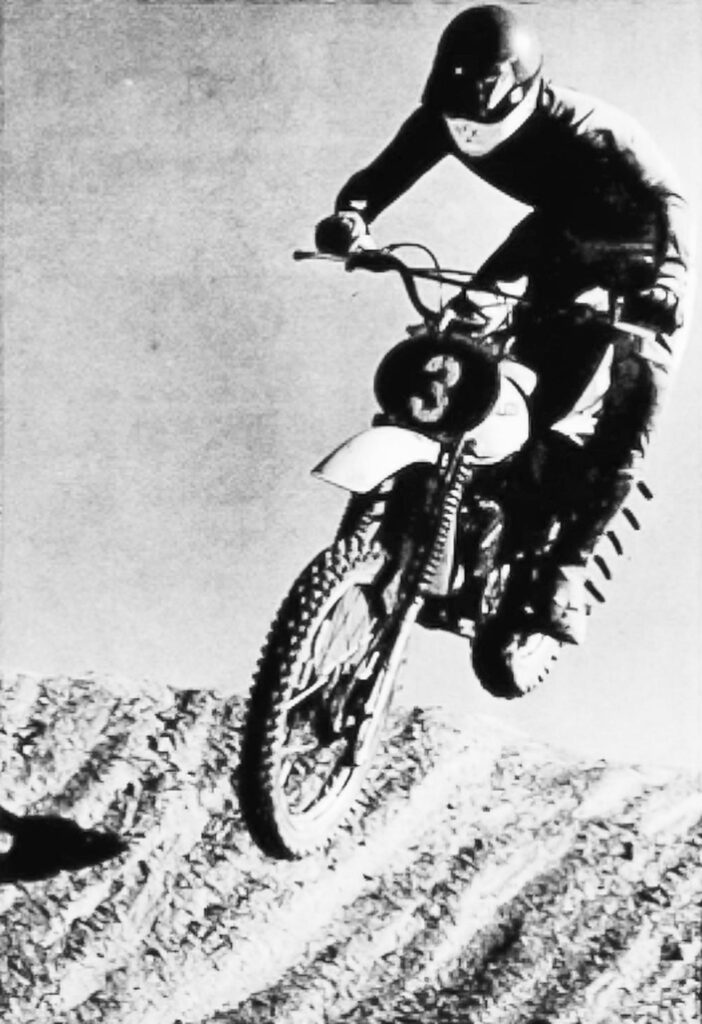

Suzuki had several MX models that out-performed all others in the 1970s, when motocross bikes improved exponentially every year. The 1977 RM125B was one of those bikes.

Suzuki had several MX models that out-performed all others in the 1970s, when motocross bikes improved exponentially every year. The 1977 RM125B was one of those bikes.

The term “riding” isn’t really an accurate way to describe the job being performed by humans aboard a 125cc two-stroke motocross bike. The racer is simultaneously a gymnast, a physicist, an engineer and a horse jockey. Whereas a more powerful machine needs only more throttle to move more quickly, the diminutive little motor on a 125 needs more of everything. Want to go faster down the straights? Scoot back over the rear end, pull back on the bars, and push the soles of those Hi-Point boots into the pegs! Now, straddle that fuel tank in the loose loam, making that rear wheel light! Shift, shift and shift again, feathering that clutch until you reach two-stroke Valhalla, a land somewhere between engaged and disengaged. Your brakes are there—but do you really want to work so hard to reawaken the precious and few ponies inside the engine? Wouldn’t it be easier just to keep the throttle on, whip that beast in the flank and rail through that upcoming corner?

CN testers were up front about the RM’s demands, suggesting that it will take “a fairly expert rider to realize the potential of the RM 125B.” Their only complain seemed to be with the tightness of the beefy gearbox, which was reluctant to get through the gears without the use of the clutch, though they acknowledged that time would likely help loosen the cogs up and thus allow for clutch-less movement through the gears.

That was it! Everything else on the RM earned the praise of the test crew, which should not be taken lightly. This was still the 1970s, a time when magazine staffers treated motorcycles the way Pete Townsend treated his electric guitar. The Suzuki shined on the gnarly tracks and nothing broke. In a hint of things to come, they did opine that there was a noticeable drop in power after the engine had “been running for a long time and gotten nice and hot.” Four years later, the Suzuki RM125 became liquid-cooled.

Cycle News tested the 1977 Suzuki RM125B in January 1977 and said it “will probably be the bike in its class when it comes to tackling tough circuits” and is “heavily influenced by the Suzuki GP bikes.”

Cycle News tested the 1977 Suzuki RM125B in January 1977 and said it “will probably be the bike in its class when it comes to tackling tough circuits” and is “heavily influenced by the Suzuki GP bikes.”

The 125cc two-stroke racer was everyone’s bike. On the national scene, up-and-coming racers cut their teeth on them, but they would occasionally have to do battle with MX veterans who would swing over to the little bikes every now and then. Harry Everts, Jim Weinert and Billy Grossi were just a few of the seasoned pros who had made their names on 250s and 500s, then jumped on 125s later in their careers.

A sweet little 125cc two-stroke is a rare bird in today’s MX aviary. But not so long ago, they ruled the roost—and in 1977, no 125 flew higher than Suzuki’s RM125B. CN