| February 11, 2024

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

How Bad Could It Be?

By Kent Taylor

Quickshifting, ABS, GPS, launch control, maps and modes, lean angle sensors, etc. If you think that the lineup of motorcycles available today is too busy with all their gizmos and wizardry, then turn back the clock to revisit the days of simpler two-wheelers. Could we interest you in an air-cooled, four-stroke single with telescopic forks, drum brakes and a kickstart lever?

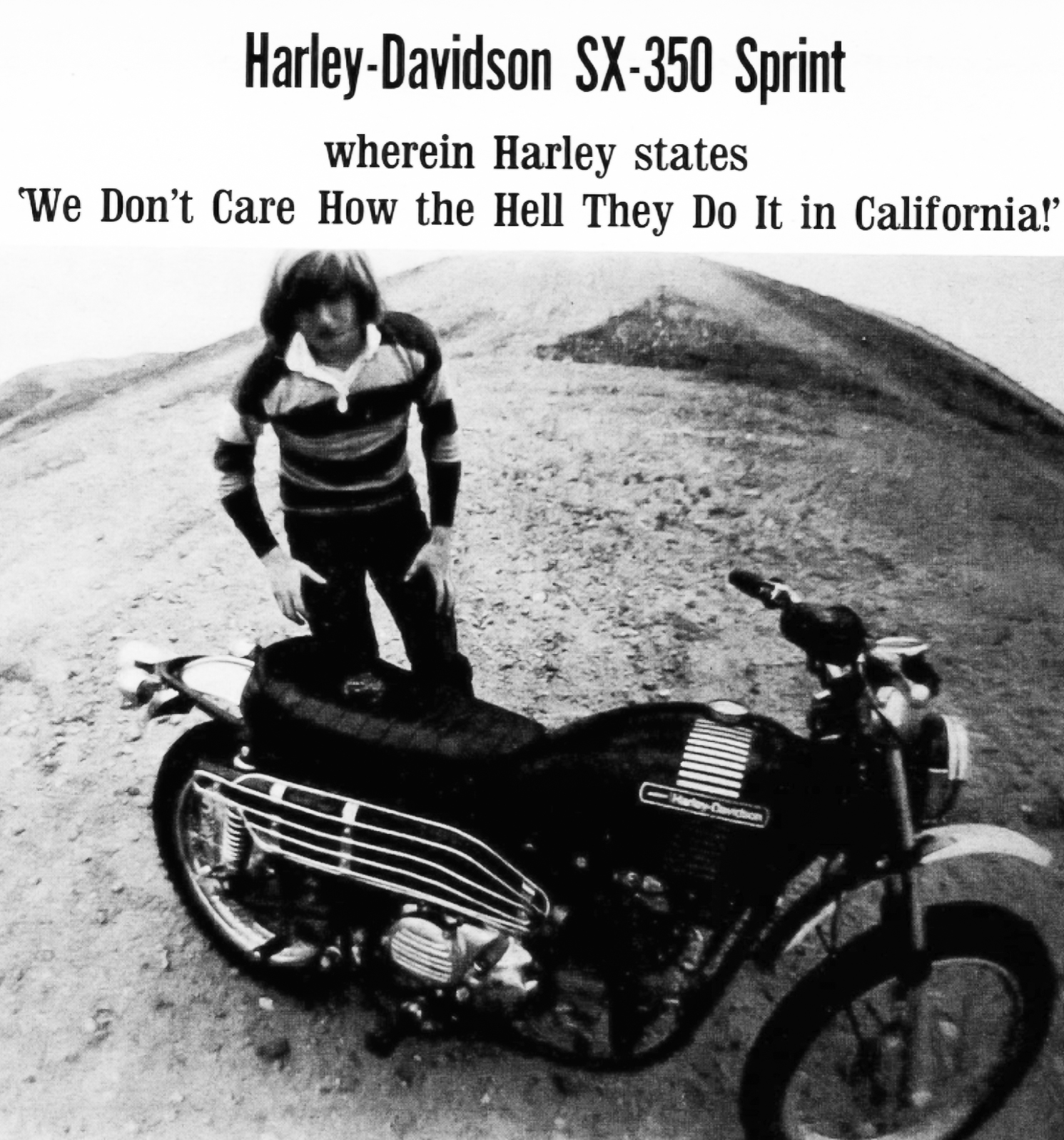

The Harley-Davidson SX 350 wasn’t one of the company’s finest moments.

The Harley-Davidson SX 350 wasn’t one of the company’s finest moments.

Such a machine was the 1973 Harley-Davidson SX 350 Sprint. A quick once-over on this Italian-made H-D reveals that there is not a whole lot in the way of high-tech—wait! There is an electric starter on the little four-banger! Punch it, and the little Harley comes to life!

And that’s when the trouble began. Cycle News tested the little thumper in its April 3 issue of 1973, the same year that The Edgar Winter Group gave us the rock classic “Frankenstein” and the top-grossing movie was The Exorcist. Unfortunately, not even a fully ordained man of the cloth could’ve chased the demons from this H-D thumper.

Motorcycle magazine tests of the 1970s were often mean, abrasive, and unforgiving, often to the point of ridicule. Staffers weren’t in the game for the love of money or fame; they were motorcyclists first, journalists second and they didn’t suffer poor motorcycles. To be fair to the Motor Company, very few bikes met the high standards of magazine testers, though it isn’t exactly clear what those standards were because nearly all motorcycles of this era were found to be lacking in some (or many areas). Weak brakes, excessive weight, and not enough power (or perhaps too much of the wrong kind of power) were common themes in these road tests.

So, Harley-Davidson shouldn’t have been waiting for a glowing review of any of its motorcycles. But after reading what CN testers had to say about the SX 350, they were likely wishing that they had never even returned editor Art Friedman’s phone call.

How bad could it be? “Discomfort,” “evil-handling,” and “far too heavy” are just a few of the phrases used to describe the experience of riding the Sprint. The staffers were quick to point out that the SX 350 wasn’t really a street bike and it wasn’t a dirt bike, the latter argument being bolstered with the tale of a test rider losing control of the motorcycle in a sand wash and then enduring the unpleasant experience of having the bike fall on him. “The resulting separated shoulder,” wrote CN, “has caused him to have considerable ill will toward the SX 350.”

The SX 350 tipped the scales at circus-lady fat 400 pounds, a figure so astronomical that it seemed as if the manufacturer had tasked the engineers with the goal of making the Harley the biggest boy in the class. For the sake of comparison, Yamaha’s 1973 DT360 listed a dry weight of 275 pounds. Not svelte by any means, but a featherweight compared to the SX 350.

A 400-pound, 350cc single? The writing was on the wall.

A 400-pound, 350cc single? The writing was on the wall.

In what seemed like an effort to make the rider feel each of those 400 pounds, Harley had outfitted the SX with weak suspenders at both ends. The Harley’s front wheel was connected to a pair of Ceriani forks, high-end components at that time, but these “forks and shocks seem to be lifted from other machines, without being thought out in terms of the frame or machine application.” At one point during the test, the forks performed a “hydraulic lockup” bringing back the feel of a “rigid frame Harley.”

The testers were equally unimpressed with the back end of the machine, stating that the shocks were “stiff enough to pop the back end of the machine up when it encounters the obstacle that the front end couldn’t clear.” Somewhere in that sentence, one might find a backhanded compliment!

If there was one important component of the SX 350 package that the test crew tolerated, it would be the heart of the bike. “If the Sprint has an outstanding virtue,” CN wrote, “it is the engine. Some tastes will find it ideal. The torquey little horizontal four-stroke single was happy as a pig at the slop trough when climbing hills. It would drag its own weight along with the operator and a passenger up a considerable grade…it doesn’t have all that much power, but [it] is perfectly adequate.”

Harley-Davidson shouldn’t take too much credit for this impressively “adequate” powerplant. The Italian Aermacchi company, of whom H-D had acquired a 50 percent share, had been building quality engines for decades. The company had begun its run in the early 1900s as a manufacturer of military aircraft. But like Ducati and its radio business, World War II had devastated the companies, and both firms, looking for a new direction, saw war-torn Europe in need of cheap, lightweight transportation for its citizens.

Aermacchi produced a series of beautiful machines and also had a brilliant run in road racing, with beloved Italian Renzo Pasolini nearly winning the 250cc World Championship in 1972. Harley-Davidson’s acquisition would put Aermacchi engines in U.S.-spec chassis, and perhaps they would now have a player in the rapidly growing U.S. market for small-displacement motorcycles.

“Harley-Davidson needs to pass back to their Italian branch the message on what will sell and provide pleasure in the American market” wrote CN. “The machine needs some serious re-thinking if it is to compete with the horde of street-oriented Japanese dual-purpose bikes.” Unfortunately, for the SX 350, that time never came. AMF Harley-Davidson dust-binned the 350 after just one more year of production, and the rest of its Aermacchi-based machines would follow it soon after. CN