| February 18, 2024

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

Modest Mike

By Kent Taylor | Photos by Dan Mahony

When his day shift at Harry D. Foster Triumph Motorcycles ended, Mike Haney laid down his spanners, put on his leathers, and, in proper British fashion, headed for teatime—or rather, TT time. Haney was a motorcycle racer, and in the 1960s, every dirt track racer worth his steel shoe made his way to J.C. Agajanian’s Ascot Park. It didn’t matter who you were or what you did anywhere else because “if you were going to be somebody in Class C racing,” Haney says, “then you had to prove it at Ascot.”

Mike Haney on his National-number-91 Triumph.

Mike Haney on his National-number-91 Triumph.

During his 12-year career, Haney was one of the fastest racers in the Southern California region, leaving many a top-ranked AMA racer eating the dust kicked up from his self-prepared Triumphs. But when Ascot’s race night was over, and the factory-sponsored AMA pros headed back out on the road, Mike collected his meager first-place prize money and drove his Ford van to Torrance, back to his day job working for Harry D. Foster. He could only imagine what he might be able to do if he could get a chance to race at places like Sedalia, Peoria, or maybe even the Houston Astrodome.

But that was just a dream, one being lived out by a handful of guys lucky enough to call themselves full-time racers. Mike Haney was a working man, a regular guy who raced for no reason other than that he loved motorcycles. His family had roots in the Midwest but replanted themselves in California, which is where 14-year-old Mike took $35 and bought his first motorcycle, an Indian V-Twin. It was his second motorcycle, however, a 350cc Velocette (a serious off-road machine in 1957) that opened the door to the world of competition.

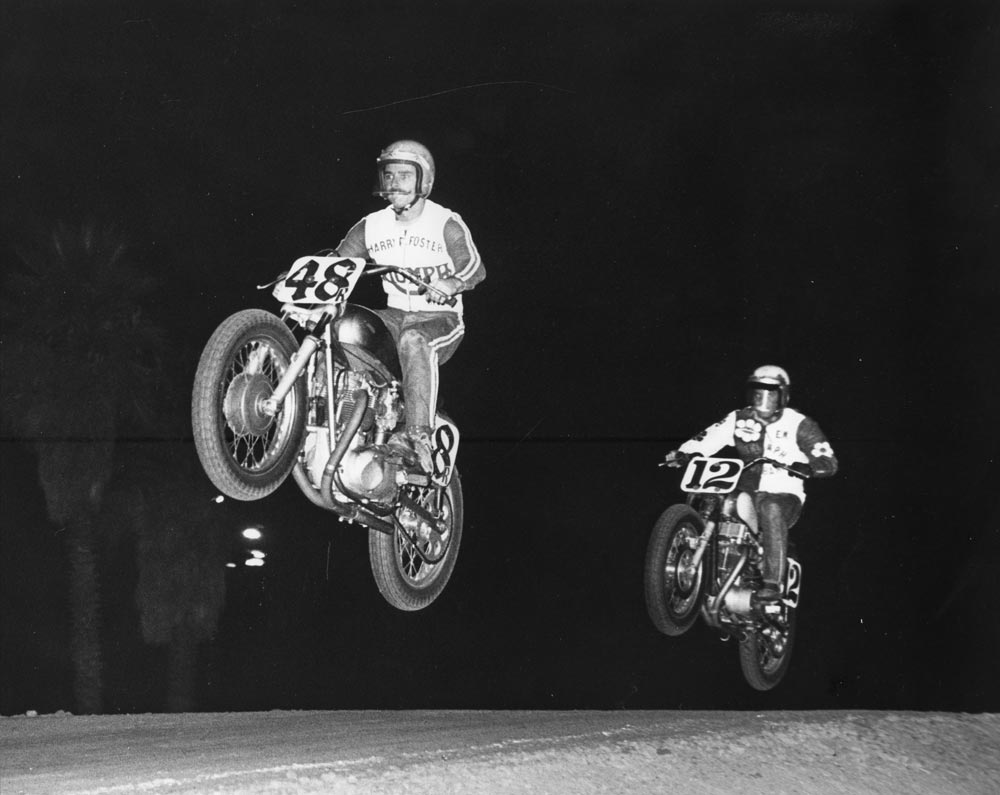

Haney, here leading Eddie Mulder, cut his racing teeth at his local track, Ascot Park.

Haney, here leading Eddie Mulder, cut his racing teeth at his local track, Ascot Park.

“Once I started racing,” Haney recalls, “that was it. It was all I wanted to do. I did scrambles, TT events, flat track, desert, and what we called rough scrambles because the term ‘moto-cross’ hadn’t come to the U.S. yet.”

Motorcycling became all his life. In 1957, he landed his job at Harry D. Foster Triumph, which was the second-oldest Triumph dealership in the U.S.

“Harry was the best guy you could ever meet. He would give you the shirt off his back,” Foster said. “And he was a great mechanic. I tell people he could make chicken salad out of chicken poop.”

Foster provided Haney with steady work but stopped short when it came to Haney’s race effort. “He was supportive, but the only sponsorship I received was being able to buy parts at dealer cost,” Haney remembers. “I did the rest of it all by myself.”

He had received his AMA Class C professional license in 1962, but it would be a full decade later before he made his way out of the state for a major race, the Peoria TT in Illinois. At the famous TT track, he qualified well and rode hard, narrowly missing out on a podium spot. “I had passed Mert Lawwill and was running in third for most of the race. Mert wasn’t going to let some no-name like me beat him, so he passed me back on the last lap!”

Peoria was a tough track, and Haney’s impressive fourth place showed the Class C world that he wasn’t just a one-trick pony, an Ascot specialist who could only win in his own zip code. But when the race was over, Haney, once again, returned to his home state, back to his job at the Triumph shop where he made $120 per week.

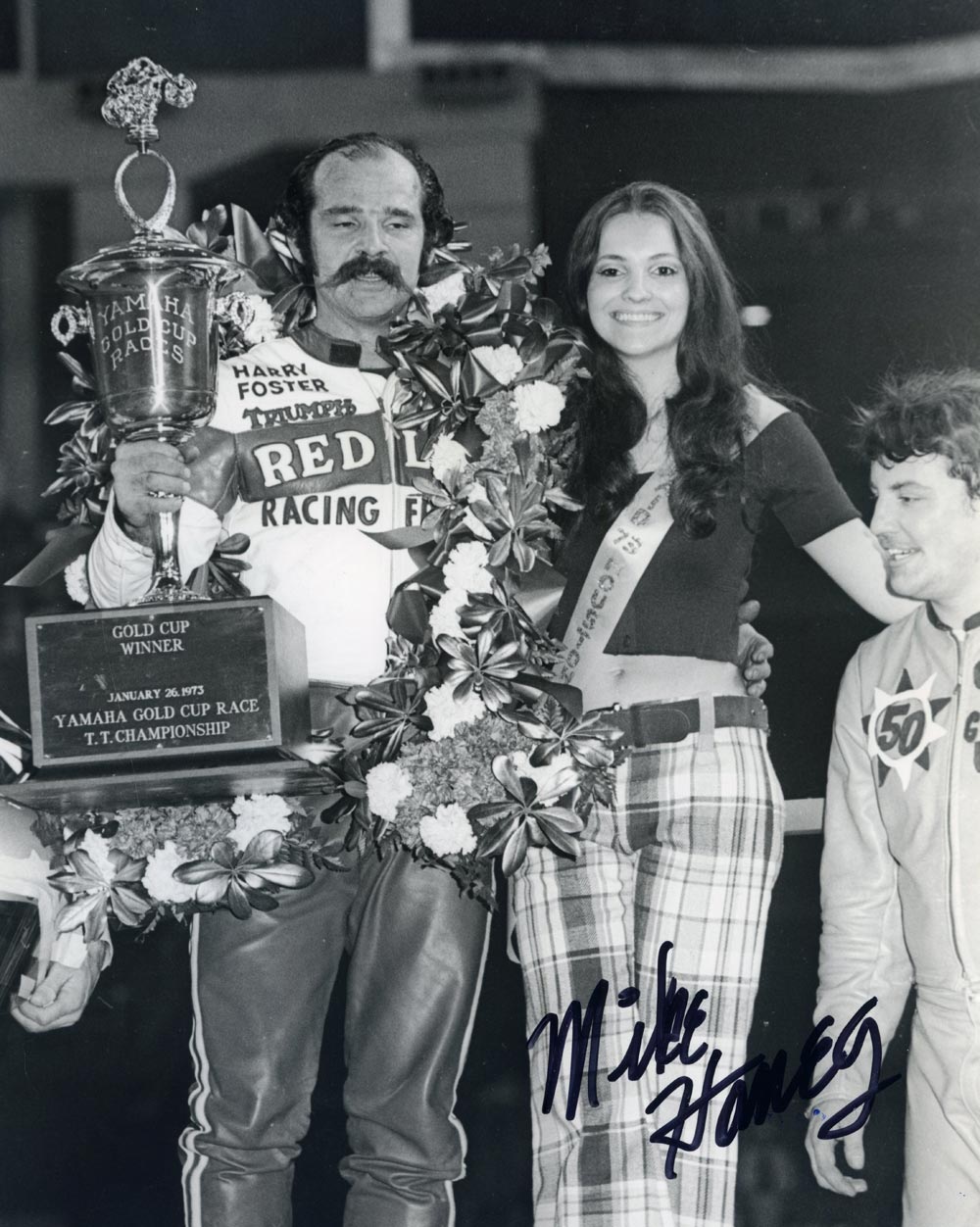

One of Haney’s claims to fame is winning the Houston TT in 1972.

One of Haney’s claims to fame is winning the Houston TT in 1972.

In the fall of ’72, Haney took a visit to a California frame shop where they welded up Redline frames. In the 1970s, every serious dirt track racer had a Redline frame, which was designed specifically for competition. He was chatting with owner Lynn Kasten, a conversation that eventually led to the workshop where Kasten showed Haney a brand new, race-ready chassis. A Redline frame was admission to the show, but it came at a ticket scalper’s price of $410. “That was a lot of money in 1972,” Haney says, “especially when you’re making a hundred bucks a week!”

While Haney stared at the chassis, likely thinking about the possibilities, Kasten dropped a bombshell. He told him the frame was his, absolutely free of charge—sort of!

“Take it to the Houston,” Kasten said. “Win the race and it’s yours!”

Houston, of course, meant the Houston Astrodome TT. It was the first National of the year, the race that every major motorcycle magazine covered, the highest-paying dirt track race of the year, the race that every team and every rider wanted to win. And all Mike Haney had to do now was be the one rider who actually would win!

Likely already thinking about how he might have to come up with $410 for Kasten’s frame, he loaded up his new Redline-framed Triumph and headed to Houston in February. He had plugged in his own very competitive engine. “I always built my own motors, and this one was very tractable. It wouldn’t have been good on the miles, but it would work well that night.”

“Houston was one of the most difficult races on the circuit,” says Tom Horton, an AMA dirt track racer from 1971-77. “It was rebuilt every year, of course, so the dirt was always different. It was a difficult night of racing, and sometimes even the biggest names would struggle to even qualify for the main event.”

The rest of the field got a glimpse of Haney’s skills when he pulled off a win in his heat race. He got a good start in the 20-lap main, right behind a young Yamaha rider named Kenny Roberts. Haney, who was 10 years Roberts’ senior, stayed close in the early going. A second-place finish to a future National and World Champion would’ve been a strong showing.

But on lap five, Roberts clipped a hay bale and was down on the ground. Haney motored past and into the lead. Kenny was quick to remount and rejoin the race, but Haney slid, jumped, and roosted his way to victory in the most prestigious dirt track race of the year.

“I was never nervous,” Haney remembers. “Not once. I just made sure I rode smoothly and didn’t do anything stupid. I remember there was a huge hole that was forming in one of the corners. Every rider would hit that hole, wobble, and bounce and nearly crash. I just went around it!”

Haney collected $3500 for his win that night, which included a $600 bonus from Triumph. After he returned to California, he began dreaming about the next step in his career and even used some of the funds to purchase a Triumph road racer. Mike Haney was going to Daytona.

It was a bike he would never race.

A few weeks after Houston, Ascot Park put on a 100-lap TT. Haney was there, along with most of the other top racers. He was running well when “I missed a shift, and the bike popped into neutral.” Haney and his Triumph crashed hard into the wall, and his left leg snapped in two places.

“Back then, you just couldn’t get the kind of care that you can today,” Haney says. “They reset it, but it broke again. They put rods in it, took the rods out, and it just kept breaking.

“They would take the cast off, and my leg would look like my arm, just skinny and hanging there. Eventually, I found a doctor who fixed it correctly. It took five years, and by that time, it was a full inch and a half shorter than my other leg.”

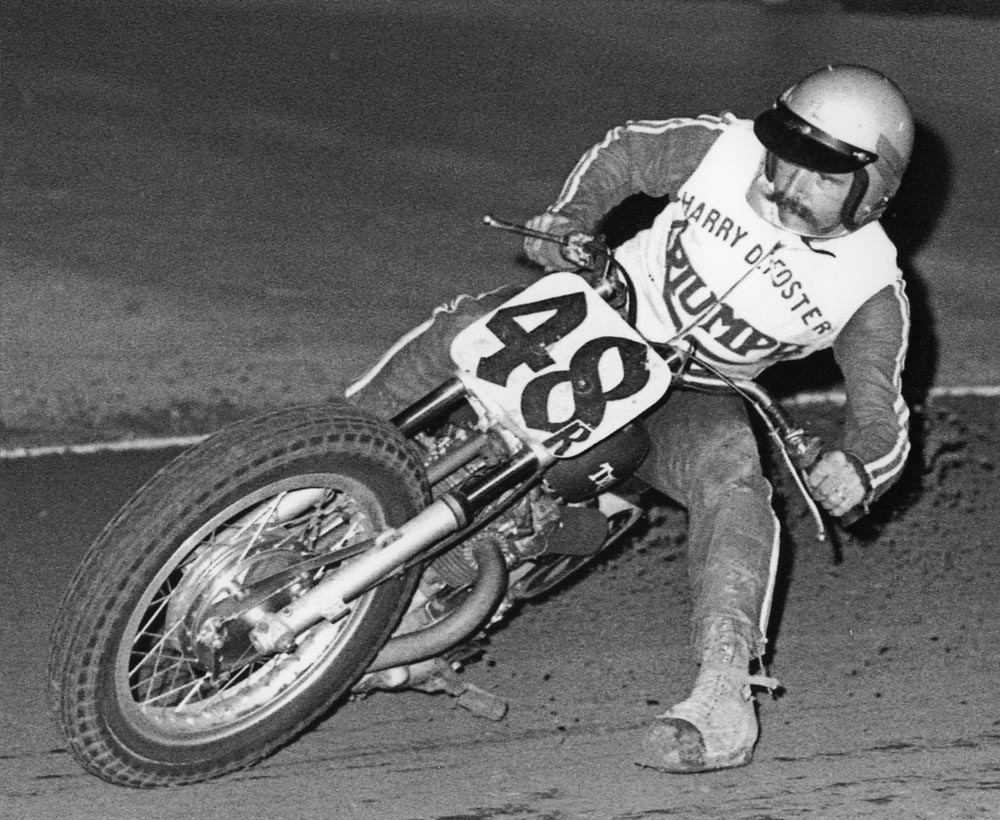

Haney was on the cusp of making it big time in racing when a leg injury prevented that from happening.

Haney was on the cusp of making it big time in racing when a leg injury prevented that from happening.

Haney returned to the life that he knew, working on Triumphs. He and a partner purchased the dealership and kept it going until 1990. Today, he lives in the desert and is still working on Triumphs, restoring old machines for those with a fondness for the old British bikes.

In April, Haney will be honored with an induction into the Trailblazers Hall of Fame.

“He’s one of the most humble men I’ve ever known,” says Tom Horton, former racer and Trailblazers’ Board Member. “We call him ‘Modest Mike.’ But he deserves his place in the Hall. He’s earned it.”

“I just look around at my world and laugh sometimes,” Haney says. “I live right next to my shop and get to work on motorcycles all day. And I still ride. I’m 80 years old, and I have everything I ever wanted in my life.” CN