| September 10, 2023

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

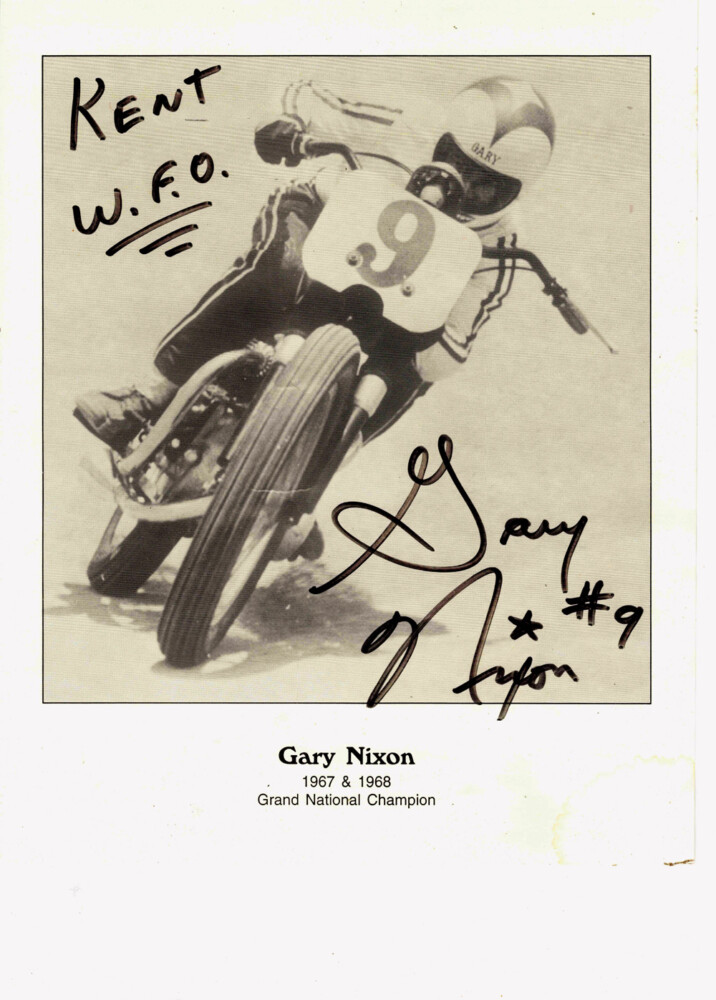

WFO Always

By Kent Taylor

Gary Nixon dashed into the trailer, quick to oblige the fan who had asked for a photo of the two-time Grand National champ. Nixon, who had hung up his leathers many years earlier, now seemed energized that this race enthusiast had sought him out and was even asking knowledgeable questions about his career.

“Here ya go,” he said, returning with a black and white 8 x 10 photo of himself, sliding his big number-nine Triumph. “I signed it [his signature star dotting the “I”] and I also put ‘wfo’ on there.

“And that,” he added, with a dead-eye look, “stands for wide f***ing open!”

Most every racer knows (but playfully doesn’t reveal) what “WFO” means. Perhaps, it’s wound full out? But in that moment, that old race yarn was inexplicably something more than just bench-racing lingo. Because, like E.F. Hutton, when Gary Nixon talks, people listen.

“That was definitely Gary Nixon,” says his longtime friend and former teammate Don Emde. Brash, extremely honest and upfront, those who had the honor of knowing Nixon knew that you would get it straight up from the red-headed racer from Oklahoma.

“Upfront” was exactly where race fans would find Nixon, 50 years ago in 1973. Of the nine road race events on the AMA schedule that season, Nixon handily won three of them and challenged for the win in at least three others. While perhaps that is not Jett Lawrence-style domination, it was about as close as one could come at a time when the field was overloaded with talent. 1973 was the final season for legends like Cal Rayborn, Geoff Perry and Jarno Saarinen, who would all start alongside Kenny Roberts, Paul Smart, Gene Romero and Kel Carruthers, to name just a few of the greatest names in the history of the sport who would be racing together for the last time. (Rayborn, Perry and Saarinen would all lose their lives in separate incidents later that season.)

It was also a transitional season in the technology game: the crackling of liquid-cooled two-stroke 350s, two-stroke 750 triples (both liquid and air-cooled versions) shared the airwaves with the throaty four-strokes from Triumph, Harley-Davidson, Norton and BMW. While the four-bangers were well on their way to the history books, they were still competitive in ’73.

Fifty years ago, Gary Nixon was at the top of his game.

Fifty years ago, Gary Nixon was at the top of his game.

The road racing season began, as always, at Daytona. Nixon and his Kawasaki teammates Art Baumann and Yvon Duhamel took turns leading the field that day. Duhamel and Baumann both crashed and Nixon took over for 10 laps before his Irv Kanemoto-tuned machine seized. Nixon, who hadn’t won an AMA National in three long years, would have to wait a little longer to taste victory.

It would come in late June, at Loudon, New Hampshire, on a racecourse which the late CN writer Gary Van Voorhis called “Nixon’s track.” He would take the lead away from Kenny Roberts midway through lap one and would not look back, leading the remainder of the way to win the 75-mile national.

“Gary won Loudon,” Van Voorhis wrote, “and he did it BIG!” He even lapped Dick Mann, who finished ninth and stretched out his lead to 35 seconds at the finish. Nixon probably had time enough to strip his leathers to his waist and light a cigarette before second-place Kenny Roberts would even see the checkered flag.

That same weekend, Nixon held Roberts to another runner-up spot, narrowly winning a fiercely fought battle in the 250 Expert/Junior combined race.

A month later, Nixon was on top again, this time at Laguna Seca. The race had belonged to Duhamel, but when the French Canadian crashed in the corkscrew, Nixon took over and held off teammate Cliff Carr for the win. “I think my luck’s changed,” he said after the race.

It certainly had, and it would continue just a few weeks later at Pocono, Pennsylvania, where Nixon scored his third consecutive road race win. Taking the lead from Duhamel again (whose Kawasaki broke down), Nixon scored another win, with Kenny Roberts again in second place.

After three years without a win, Nixon had now won three races in a row. According to Emde, it couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy.

“I met Gary when I was still a novice in 1970,” Emde recalls. “He was really a hero of mine, but he became a good friend. My dad and I would stay at his house when we were back east. It wasn’t a large, fancy house by any means, but it was full of some great racers: John Hateley, Don Castro, Dave Aldana, and a lot of riders would be staying with Gary and his family. He showed us the ropes, coached us and helped us in any way he could.”

Nixon and Emde were members of the powerhouse Triumph/BSA team of the late ’60s and early 70s. But the sudden collapse of the British bike industry left both he and Emde scrambling to find new rides at the end of 1971. “We were 90 days out from Daytona,” he recalls, “and that wasn’t much time to find sponsors, build new race bikes and so on.”

Emde fared well, landing a Mel Dinesen-sponsored ride on a Yamaha 350 on which he won the 1972 Daytona 200. Nixon, meanwhile, struggled his first year on the Kawasaki. The talent was there, and he even won the first leg of the Ontario 200. But he crashed in the second leg and broke down in most of the other races throughout the year.

If there is any truth in the saying “you make your own luck,” then Gary Nixon decided to make 1973 his luckiest year ever by forming what would become a longtime partnership with famed tuner Irv Kanemoto. Together, the two men helped give Team Kawasaki one of its most successful race seasons ever.

With maybe just a little more luck, Nixon might’ve won even more in 1973. At Road Atlanta, he was out in front in his heat race when a connecting rod snapped in two. At the season finale, he finished second in both legs of the Ontario 200, challenging Duhamel in the final before settling for second.

According to Emde, second wasn’t a place where Gary Nixon liked to live.

“He might’ve been the first guy to ever say ‘second place is the first loser,’” Emde says. “He truly seemed pissed off when he didn’t win. He just really had a drive to be on top.”

“Gary struggled with life when his racing career ended,” Emde adds. “He was born to be a racer, and I think that was really all he knew how to do.”

Nixon continued to win races over the next several years for both Suzuki and Kawasaki before finishing his career aboard a Yamaha TZ750. He had a brief stint managing a dirt track racing team, as well as running a catalog order business.

Gary Nixon passed away in 2011 at the age of 70, but before he left, he gave race fans one more chance to watch the fiery redhead do what he did best. It was in the early ’90s; Nixon returned to racing with the BMW Battle of the Legends series, where he would win at Daytona one more time!

“It was all for show, a promotional event for BMW,” Emde says, “but Nixon took it very seriously. And when he won, he was smiling again.

“He was just like his old self.” CN