| June 25, 2023

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

That Girl

By Kent Taylor

They didn’t have the term “toxic masculinity” in the 1970s, so there was no clinical way to properly describe what was about to take place that day at Holiday Downs, a high-banked, 3/8ths-mile, red-dirt racetrack in Palmetto, Georgia. But as he sat on the line, waiting for the race to begin, this particular teenaged male could hear his daddy’s voice in his head, and he knew exactly what his words meant: “You can’t let that girl beat you tonight!”

Tammy Kirk runs her own Honda shop, Kirk’s Cycle, in Dalton, Georgia.

Tammy Kirk runs her own Honda shop, Kirk’s Cycle, in Dalton, Georgia.

If only the youngster knew who “that girl” was going to become, if only he could have taken just a little peek into a crystal ball. With a quick glimpse into the future, he could’ve told his pa, “that girl” was none other than Tammy Jo Kirk and that in a few years, she was going to wrestle a Harley-Davidson XR750 into the main event at Knoxville, Tennessee, a feat that was going to make her the first woman ever to qualify for an AMA Grand National Dirt Track race.

Or maybe he could’ve peered ahead into 1986 to the Du Quoin Mile, where she was going to chase nine-time Grand National Champion Scotty Parker to the checkered flag, narrowly missing out on a top five finish in the main event. With all of this information in hand, maybe his pop would’ve called off the “dawg” in the boy and told him to just do the best he could against this girl racer.

But you don’t have (or need) crystal balls to go motorcycle racing, so when this kid decided that the only way he was going to beat Tammy Kirk that night was to stuff her into the Holiday Downs’ fence, he found out that girls can not only ride fast—they can punch hard, too!

“I was a’wailing on that kid after the race before my dad came over and pulled me off him!” Tammy says today, with a Georgia accent so thick it sounds like it was just pulled hot from the smokehouse. “I was only 12 years old, but I was getting tired of this kind of stuff!”

“Stuff” for Tammy was her description for another term that had yet to be invented. Its name would be “gender discrimination,” and it became her fiercest competitor, lasting through her entire career. It fought her on the racetrack (“boys did not like getting beat by a girl”) and in the race shop, where she learned that girl racers were cute novelties, but successful women competitors were a threat.

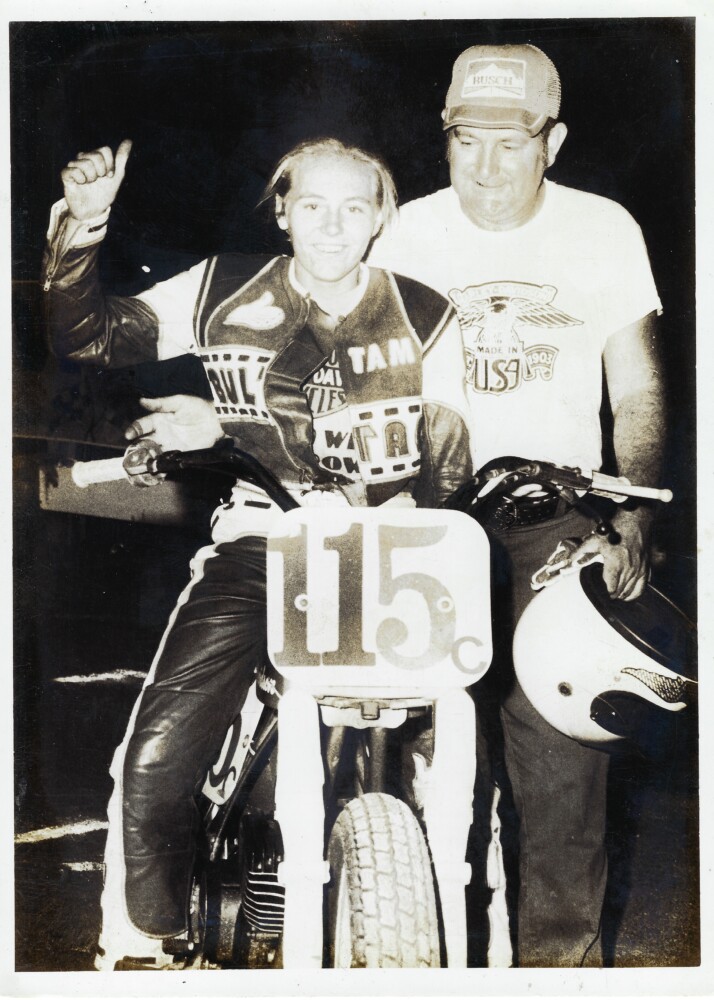

Tammy and her father, Tommy, were quite the team. Tommy made sure Tammy had what she needed to beat the boys.

Tammy and her father, Tommy, were quite the team. Tommy made sure Tammy had what she needed to beat the boys.

Tammy Jo was the middle of three sisters born to the Kirk family on May 6, 1962. Her father, Tommy Joe Kirk, was a welder by day, a racer by night and a Bultaco dealer for fun. Operating the dealership right out of the family home in Dalton, Georgia, Tammy and her sisters grew up around motorcycles. “As soon as I could walk,” she says “I was on a motorcycle and I would ride from daylight to dark.”

Racing was an important part of the business for Tommy; in addition to being a competitor himself, he sponsored Grand National dirt track racer Roger Crump for several years. When Tammy was ready to go racing, the entire family got behind the effort.

“We spent almost all of our money to go racing,” she recalls. “We didn’t even buy new furniture for the house—had the same things for 20 years! When my older sister got a job, she put her money into our race effort, even though neither she nor my younger sister even rode a motorcycle!”

It didn’t take long for Tammy to see that girls who play boys’ games would have to fight just to get on the track. “We went to a race in Alabama,” she remembers, “and the promoter said, ‘sorry, we don’t have a Powder Puff class’ for her. My dad said, ‘well, she’s here to race against the boys’ and of course, he responded ‘well, she can’t do that’ and that was almost the end of it.

“But my dad wouldn’t let it go. He said, ‘are you afraid of her? That she’s going to go out and beat all of these boys?’ So, the guy relented and I got to race.

“And I did beat all of the boys, too,” she adds!

It became the game that Tommy and Tammy would have to learn to play, almost every time they would visit a new track. “Dad would have to shame the promoter into letting me race.”

And, just as she discovered that night at Holiday Downs, boys would ride harder and sometimes even out of control, as they tried to beat the fast girl from Dalton.

“We knew the dad of that kid,” Kirk says. “He was always putting pressure on his son to not get beaten by me. It was always a challenge for us.”

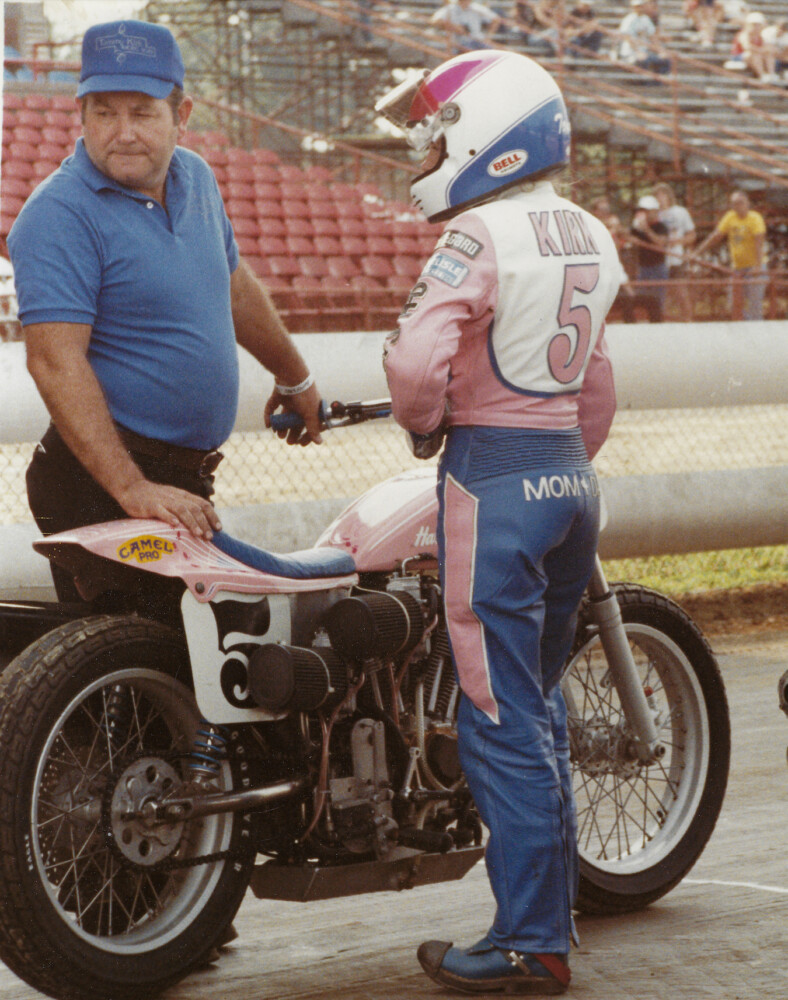

In 1983, Kirk became the first female to qualify for an AMA dirt track final.

In 1983, Kirk became the first female to qualify for an AMA dirt track final.

Tammy’s career advanced to the AMA Grand National circuit; as a novice and junior, she battled riders like Billy Herndon on her way to obtaining her Expert license in Class C racing. She connected with Lawrence “Smitty” Smith of Smitty’s Harley-Davidson in Moundsville, West Virginia, who put her on what was going to become her favorite motorcycle—the XR750.

“I loved going fast” she says today “and I loved that motorcycle. I only weighed 115 pounds back then, so it was kind of a challenge on the half-miles, but I really felt at home on the miles.

“I really loved to go fast.”

Tammy Jo put her affinity for speed to the test on a historic night, June 25, 1983. At the Knoxville Half-Mile National, about 100 miles from her hometown of Dalton, she tucked in behind Jay Springsteen, as they both chased down third-place man Rob Crabbe in their heat race. As she told Cycle News: “Jay moved up about two feet higher than the line I was riding to around Crabbe, so I did the same and passed Rob like he was tied to a stone.”

In the main event, a loose condenser knocked her down from a probable eighth to a 14th-place finish at the checkered flag. But nothing was going to rein in the jubilation that Tammy and her team felt. The future was bright and the sky was the limit, right?

“Things started to change for me, just because I was a female,” Tammy says. “In those days, you couldn’t just order XR750 parts from Harley-Davidson. They wanted to know who it was for. All of a sudden, parts weren’t available to me. We couldn’t get rods, cranks, cases, etc. All of the things that the guy racers had were off limits to me.”

Her best finish was sixth at the Du Quoin Mile in 1986.

Her best finish was sixth at the Du Quoin Mile in 1986.

Professional racers know how to work the system, so Tammy and her father enlisted the help of a friend named Art Delore. Art worked at an H-D shop and had the right factory connections; still, he had to tell The Motor Company that the parts he needed were for another racer and not for the woman who was now regularly defeating many established dirt track stars.

Despite the struggle, Tammy had a long career on the AMA Grand National Circuit. Her sixth-place finish at the Du Quoin Mile in 1986 would be her best ride. She raced her last National in 1989 at the Springfield Mile, where her beloved XR punched a rod through the front cylinder. Tammy parked both the Harley and her AMA career that day and soon would embark on a successful four-wheel run in both the Craftsman Truck Series and the NASCAR Busch Series. In 1994, she won the Snowball Derby, a 300-mile asphalt race for super-late-model stock cars.

Tammy would eventually open her own Honda shop, Kirk’s Cycle in Dalton, Georgia. She looks back on her racing career and says, “we did good for what we had. It was a mean business sometimes and there were some very big names in dirt track who I knew weren’t playing by the rules. At least two different teams once begged me not to protest them.”

Still, Tammy says, “the good times outweighed the bad.”

A sports’ dad and his daughter develop a special bond. Tommy Kirk passed away in 2020 and Tammy is flooded with emotion as she remembers her biggest supporter, the man who took on the system and stood behind his girl racer as she played a boys’ game.

“A few years before my dad passed away, we had Don Tilley rebuild my old XR, which had sat for 20 years with that broken rod. We got it running again—it could go racing today! I was so glad he got to hear it run one more time!” CN