| May 21, 2023

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

Italy’s One And Only

By Kent Taylor

Team Yamaha’s Gary Fisher looked on from his pit area at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds. It was May 20, 1973, and the second heat race of the San Jose Half-Mile had just ended. At the checkered flag, Lloyd Houchins, a 25-year-old dirt track racer from Castro Valley, California, collided with fellow racer Pat McCaul and both riders went down hard. McCaul was uninjured and walked away, but Houchins, thrown from his Harley-Davidson into a guard rail along the fairgrounds track, isn’t moving. Fisher and his fellow racers are waiting for information, painfully aware of the fact that at times like this, no news almost always means bad news.

Minutes before receiving the word that Lloyd Houchins’ injuries were indeed fatal, that he had died almost immediately after hitting (and snapping in two) a 4×4 wooden post, Team Yamaha manager Pete Schick brought Fisher more grim news: there had been a gruesome crash at the Gran Premio Delle Nazioni (Nations Grand Prix) in Monza, Italy, one that had taken out multiple riders. Jarno Saarinen, whom Fisher had just battled (and nearly defeated) just weeks earlier at the Daytona 200, was dead, as was Harley-Davidson’s Renzo Pasolini.

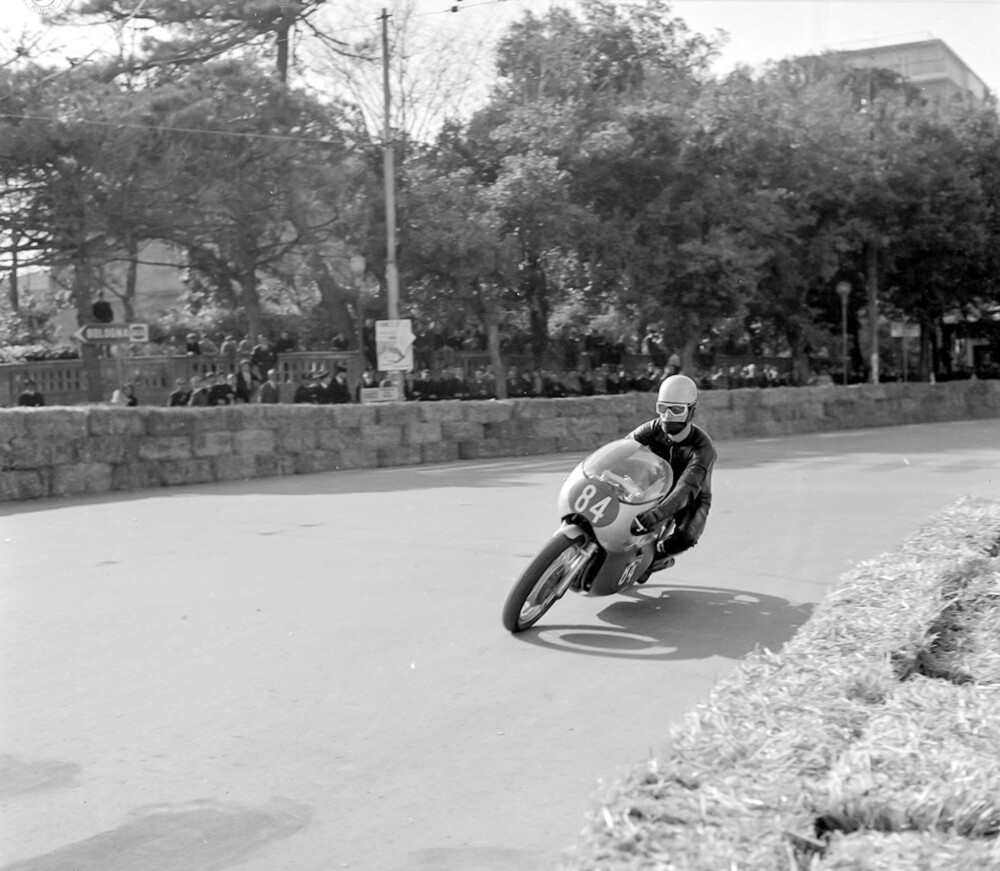

Renzo “Paso” Pasolini

Renzo “Paso” Pasolini

A likable privateer dirt tracker (see sidebar), a World Champion and an immensely popular Italian racer, one whose funeral procession would clog the streets of Rimini, Italy, with 20,000 devoted followers, were now gone. May 20, 1973. Motorcycling’s Black Sunday—on two continents.

Finland’s Jarno Saarinen was the 27-year-old reigning World Champion, a former ice racer who was likely on his way to two more titles (250cc and 500cc) that season. He had been victorious at both Imola and Daytona, where he had ridden a calculated race and defeated a talented field of riders on machines twice the size of his Yamaha 350. His life story is well known and can be found here in a previous Cycle News Archives.

At a grizzled 34 years of age, the cigarette-smoking Pasolini should have been on the parade lap of his 10-year racing career. Instead, just a few months earlier in the fall of 1972, he had topped America’s best racers with an impressive third-place finish at the AMA National at Ontario Motor Speedway. And on this day at Monza, the same track where he had been victorious two years earlier, he was in first place, leading Saarinen and many of the world’s best racers before the deadly crash.

Renzo “Paso” Pasolini was born in 1938 in the province of Rimini, Italy. Rimini is a province located along the Adriatic Sea; fittingly, one of young Renzo’s early motorcycle rides would end in the water! It was not a fully sanctioned ride, as Renzo’s father, Massimo Pasolini (himself an Italian racing champion) wasn’t aware that his young son had taken one of his father’s motorcycles for a ride la felicità!

In 1972, Pasolini was nearly champion, losing the 250cc World title to Jarno Saarinen by a single point.

In 1972, Pasolini was nearly champion, losing the 250cc World title to Jarno Saarinen by a single point.

As a young man, Renzo tried his hand at motocross (and both hands at boxing) before embarking on his career as a road racer. His endeavor was interrupted by a two-year sabbatical to fulfill his Italian military obligation, meaning that Pasolini was 26 years old before he scored his first Grand Prix points, ironically, at the Nations Grand Prix in Monza in 1964.

He would go on to race at the greatest tracks around the world, including the Isle of Man, Assen, Daytona and Ontario. Pasolini rode for Aermacchi and Benelli, storied Italian brands to be sure, but also machines that were often inferior to the MV Agustas ridden by Hailwood, Read and Agostini. In 1972, Pasolini was nearly champion, losing the 250cc world title to Saarinen by a single point.

Pasolini, who often sported googly-eye stickers on his helmet (nearsighted, he often joked that “with two extra eyes, I can see the track better”) had a much different attitude about racing.

“I ride,” he would say, “for the pleasure of riding. And if I win, so much the better!”

Off the track, he was easily recognizable with his horn-rimmed glasses and an ever-present cigarette. When the green flag dropped, fans could quickly spot Paso, as he was the rider with the safety helmet that was always a generation behind the times. Long after other riders had switched to a three-quarters helmet, Pasolini was still competing with his old pudding pot. By the time he finally embraced the three-quarter version, his competition was wearing full-faced headgear.

Regardless of his choice in helmets, fans throughout Europe lined the streets to (closely) cheer on Paso as he garnered his six career Grand Prix victories.

“Remember,” says Sergio Rastelli, president of the Renzo Pasolini Motoclub in Rimini, “until 1970, motorcycle grand prix racing took place on circuits that were laid out in cities. It allowed the spectators to get very close to the racers.”

“Unfortunately,” he adds, “it was also very unsafe.”

Pasolini’s first venture to the USA came in late 1972. His sponsor, the Aermacchi factory, was now under the wing of the Harley-Davidson Motor Company and Race Team Dick O’Brien wanted to add Pasolini to his powerhouse lineup of Cal Rayborn and newly crowned Grand National Champion Mark Brelsford.

“We had shipped an XR750 to Europe for Pasolini to ride, get accustomed to, make adjustments and such,” recalls Peter Zylstra, a former racer turned draftsman for Harley-Davidson. “It was one of the new aluminum barrel models that had the new three-piece crankshaft. A vast improvement over the old iron-barrel models.”

“It was a very big deal back then to make such a major decision,” adds assistant racing engineer Clyde Denzer. “Dick O’Brien wouldn’t have taken it lightly. But he was a master at recognizing both talent and personalities.”

“Dick bled orange and black,” Denzer elaborated. “If you were riding for Harley-Davidson, he expected you to carry yourself well. He believed that the racers were his business card from the Motor Company.”

Despite the language barrier, the affable Italian made a good impression on his American team. Pasolini was assigned H-D race mechanic Ray Bokelman for the Ontario race; the two connected so well that Denzer, Zylstra and other H-D employees added a taste of Italy to Ray’s surname, dubbing him “Boka-lini!”

“For the rest of his life, ‘Bokalini’ was our name for Ray,” Denzer says.

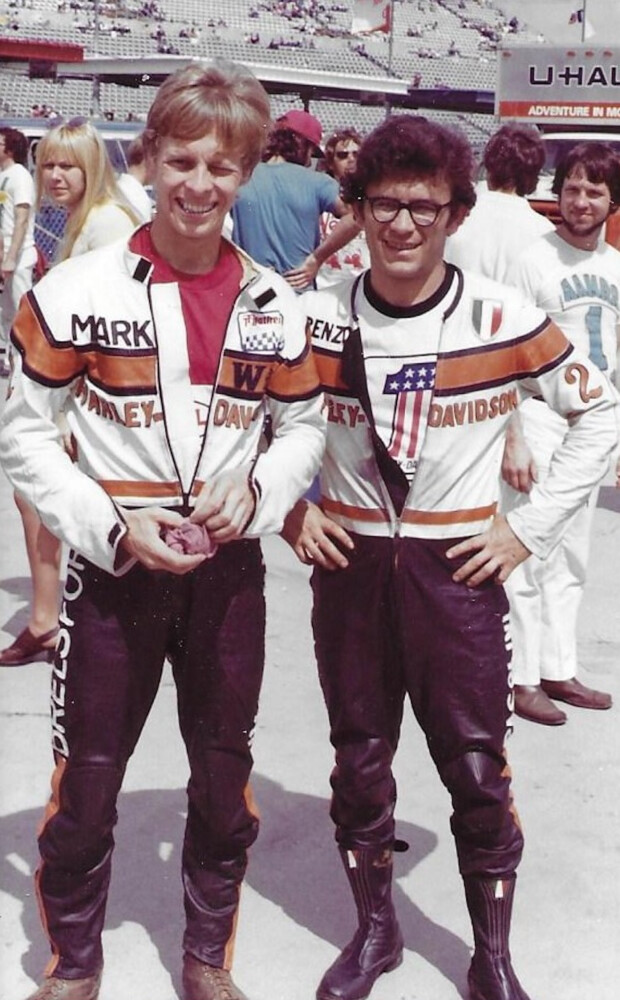

Pasolini (right) with teammate Mark Brelsford.

Pasolini (right) with teammate Mark Brelsford.

Cycle News’ account of the race (held in two heats) tells a harrowing story of an almost Jekyll-to-Hyde-like mutation. In heat number two, “Renzo Pasolini undergoes an amazing transformation. Until now, he has been riding smoothly and inauspiciously. Now he begins to really push. Tires chattering, leaned over at crazy angles, he begins to charge…”

Despite the big Harley “missing badly on the front straight,” Pasolini battles teammate Mark Brelsford and eventually garners a third overall on the day, behind Kawasaki rider Paul Smart and Suzuki’s Geoff Perry.

The details of what would take place eight months later at Monza were fuzzy even back in 1973 and 50 years of speculation have done little to provide clarity. All agree, however, that there was oil on the track, dribbled from a machine in the 350cc race which ran prior to the 250cc event. Dave Friedman, a longtime race photographer, was at Monza that day.

“There were riders arguing with the organizers, threatening to not race if that oil wasn’t cleaned up,” he says. “Finally, they did clean it, but it was a half-ass job.”

End of story—except for the fact that a post-race inspection also revealed that the liquid-cooled two-stroke engine in Pasolini’s Harley-Davidson had seized. So, a locked-up engine was most certainly the cause of Pasolini’s crash, right?

“Maybe,” says Don Emde, another former Daytona winner and a racer who has taken a keen interest in the events of that day. “It depends on when it seized. Did the piston seizure cause the crash? Or is it possible that the motorcycle seized afterwards, which can also happen. If a machine lands on its right side, the throttle can get stuck in the ground, sometimes revving it into wide-open, which can certainly cause an engine seizure.

“When you throw [all of that] into the mix, it takes on the controversy like the ‘Grassy Knoll’ theory from the Kennedy assassination.”

What is known is that Pasolini led the pack into a very fast right hand bend, dubbed “il Curvone.” Suddenly, the rear end of the motorcycle skids and Pasolini is pitched into the Armco guardrail. His airborne motorcycle strikes Saarinen and soon there are numerous other riders down. Scattered hay, debris and even fire add chaos to the horrific scene. Both riders are killed instantly.

“I was waiting to see Pasolini, Saarinen and all of the others,” Friedman says. “But the only rider who came through at the end of the first lap was Dieter Braun, and I knew something was wrong.

“They didn’t even officially stop the race. The rest of the riders just eventually pulled into the pits.”

Pasolini was laid to rest in the Monumental Cemetery in Rimini, his tomb not far from famed Italian filmmaker Federico Felini. A sculpture atop the vault depicts, “the leaves of a young growing plant and the flame of passion in single image that recalls a motorcycle trophy,” according to Rastelli.

“I was very young at the time, but I recall endless lines of motorcyclists at his funeral. There were more than 20,000 people.”

Thousands attended the funeral for Pasolini after his crash in Monza, which also took the life of Saarinen.

Thousands attended the funeral for Pasolini after his crash in Monza, which also took the life of Saarinen.

In his honor, the original Rimini Motoclub was renamed, “Motoclub Renzo Pasolini.”

“In addition to sporting activities, we introduce children to motorcycle sport, with training on minibikes,” Rastelli says. “Some of the young riders are eventually taught racing skills. Our graduates include Marco Simoncelli, Manuel Poggiali and Enea Bastianini and many others.

“Explaining the enthusiasm and esteem for Renzo is not easy. He could lead and often win races on equipment that was often inferior to his competitors…like David versus Goliath.

“We teach our riders that with that kind of tenacity and talent, they too can be winners. That is Renzo’s legacy.” CN

Lloyd Houchins

There was nothing pretentious about Lloyd Houchins. After all, what kind of racer would accept and even embrace the term “Wobbly” as his nickname?

“It was what the other racers called him,” says his friend and former mechanic Steve Storz, “but by his choice, he made it his nickname.”

Houchins was a Triumph rider, who had achieved his AMA Expert status in 1968. He competed in some events in the Midwest and East Coast, but most of his racing took place on the West Coast, specifically Southern California, where he was a regular at the famous Friday night races at Ascot Park.

Lloyd Houchins

Lloyd Houchins

“He was fast and aggressive,” recalls Storz. “He was one of the guys you had to beat if you were going to win anything at that track.” But off the track “he was well liked! Lloyd was a great character—a funny guy and a real joker.”

Houchins was a journeyman racer who worked a real job as an auto mechanic in a Chevy dealership in Glendale. Storz, a native Nebraskan, served as his mechanic, wrenching on his Triumph twins.

“He got an opportunity to race a new XR750 Harley for the first time that day at the San Jose Half Mile National,” Storz recalls, “and he was really excited about it.” In the early 1970s racing, Triumph, BSA and even Norton were still winning races but “the XR750 was beginning to show its dominance over the British twins.”

Ironically, in 1973, Storz, who is today known for Storz Performance, Inc. (specializing in Harley-Davidson performance accessories) was new to the world of the H-D V-Twin. “We were Triumph guys,” he says. “We had lots of tuning and setup help from Bobby Self of Oakland Harley-Davidson, because the XR750 was all new.”

For all of the worst reasons, Storz will never forget the events of May 20, 1973.

“I was near turn four watching them exit as they were heading for the finish line and the next thing I saw were two bikes [Houchins and Pat McCaul] flying through the air and clouds of dust. I ran toward the finish line to see what had happened because it was difficult to tell where each rider landed.”

“When I reached Lloyd, it was a scene that will be etched in my memory forever. He was lying unconscious on the track and his leathers were torn open near his upper thigh and he was bleeding profusely. He had hit and destroyed one of the 4×4 wooden fence posts that lined the outside of straightaway with his leg, severing his femoral artery.

“His wife and parents were in the grandstands watching this happen. Everyone, including myself were in shock. It really made me question my involvement in the sport.

“I knew his wife, Shannan, only a little bit from seeing her at Ascot, but I wanted to help her and their toddler son if I could. I was able to get some donations from our local motorcycle club and I believe that one of Lloyd’s sponsors helped her out some, too.”

“We are still friends today and Shannan attended our Trailblazers Motorcycle Club Banquet this past April.”

Storz maintained his connection to racing, eventually working for Harley-Davidson as race mechanic, before founding Storz Performance, Inc. in 1979.