Rennie Scaysbrook | March 4, 2023

Indian Motorcycle and Tyler O’Hara prevailed in an enthralling MotoAmerica King of The Baggers series in 2022, and we took the number-one for a quick spin at Chuckwalla.

It’s quite hard to believe a bike this big and this heavy can be ridden as quickly as it can. The Mission Foods/S&S Cycle/Indian Challenger is one heck of a racebike!

It’s quite hard to believe a bike this big and this heavy can be ridden as quickly as it can. The Mission Foods/S&S Cycle/Indian Challenger is one heck of a racebike!

By Rennie Scaysbrook

“It’s a dance,” says 2022 MotoAmerica King of The Baggers Champion Tyler O’Hara of riding his title-winning Mission Foods/S&S Cycle/Indian Challenger Team race bike. “It’s like the bike has a split personality. You can ride the bike hard and shift hard and accelerate hard, but you have to be real careful with it. She likes to go fast, but there’s a method to getting her to go fast.”

The method. More than any motorcycle I’ve ever tested in my 16 years as a professional motorcycle journalist, this Indian Challenger race bike requires a calculated method to making it work.

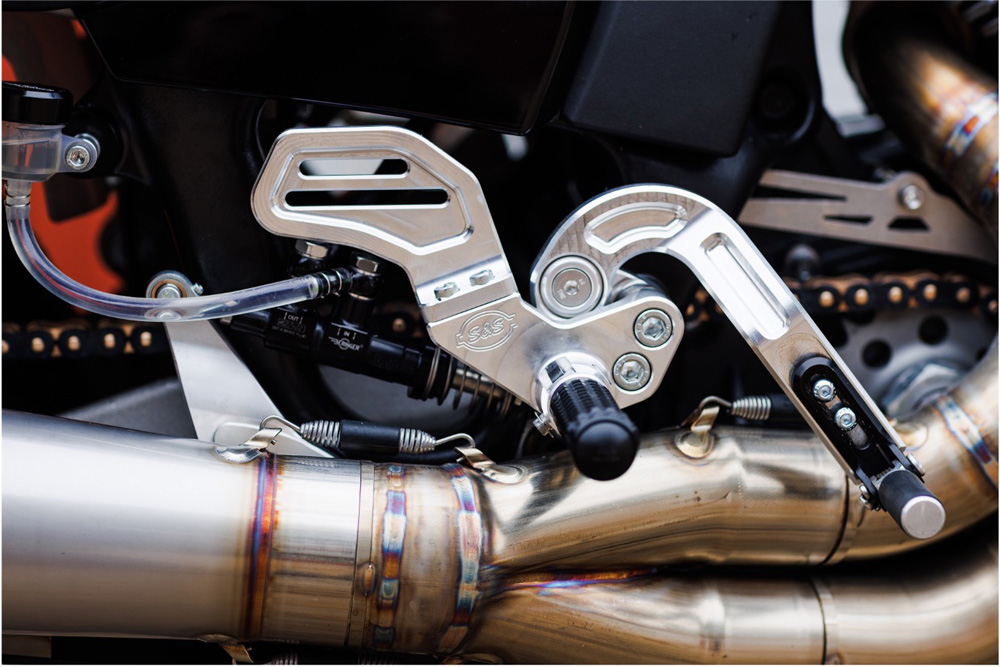

Make it a double! There’re so many bespoke parts on the Challenger, it’s hard to list them all.

Make it a double! There’re so many bespoke parts on the Challenger, it’s hard to list them all.

Long, tall, heavy and very fast, your knees are jacked at an awkward angle in the riding position, and the tank pad on O’Hara’s bike means you’re locked into place, and it makes it hard to get your weight over the front.

There’s ample room to move fore and aft, and you feel like the front wheel has been swallowed up by the massive front-end and the expansive bodywork, so it’s a matter of trust that the street-spec Dunlop Q4 we were riding rather than the race-spec slicks will do its job.

Running Brembo’s billet race caliper, a Galespeed 19 x 19 master-cylinder, and modified Ducati Multistrada 1260 Pikes Peak 48mm Ӧhlins forks, the braking capabilities and turn speed of O’Hara’s bagger are immense. Its sheer length means you can absolutely hammer the anchors to wash off speed, but it’s a double-edged sword in that the chassis really doesn’t like front trail braking, which tends to bind up the front suspension and thus make it rather recalcitrant in getting the motorcycle to the apex.

Billet top triple trees are a work of art…

Billet top triple trees are a work of art…

…as are the custom billet rearsets.

…as are the custom billet rearsets.

The secret is the use of the rear brake, which O’Hara has mounted on the left handlebar under the clutch lever, and means you need to think fast to modulate the clutch lever on downshifts and still get on the thumb rear brake to stop the rear suspension from rebounding too fast as you approach the corner.

“You absolutely have to use the rear brake,” O’Hara says. “If you don’t, it makes it very difficult to get the bike to turn tight, and you spend too much time between braking and accelerating. Plus, you can use the rear to damp out the chassis flex, which has been an issue with our bike.”

Ah, the chassis flex. The Challenger loves to squat and twist for the first half of the acceleration phase. The back end, the front end, it all moves, the chassis squirreling and squirming when you first pick up the throttle until you’re basically bolt upright and on full gas, clicking up through the quickshifter-equipped five-speed gearbox. And there’s no traction control on O’Hara’s race bike, so any force you put through your right hand via the ride-by-wire throttle will ultimately reach the tire and thus the chassis.

Tyler O’Hara ran modified 48mm Ӧhlins forks from a 2019 Ducati Multistrada 1260 Pikes Peak on his 2022 racebike. The team will change to more race-spec units in 2023.

Tyler O’Hara ran modified 48mm Ӧhlins forks from a 2019 Ducati Multistrada 1260 Pikes Peak on his 2022 racebike. The team will change to more race-spec units in 2023.

It’s par for the Indian Challenger KOTB course, and something that can’t really be changed as the rules dictate no major modifications can be made to the chassis. And that means no game-changing, flex-saving bracing.

“By rule, we can’t really modify any of the chassis parts,” says S&S’s Chief Engineer Jeff Bailey, the man largely responsible for creating, maintaining and improving O’Hara’s and teammate Jeremy McWilliams’ race bikes. “We did get an allowance from MotoAmerica to machine a bit off the front frame spars for ground clearance, but that’s really the only modification that we do to the frame. This is still essentially a street bike. It’s not a race bike at its core.”

O’Hara in action during practice for the championship-deciding round at New Jersey.

O’Hara in action during practice for the championship-deciding round at New Jersey.

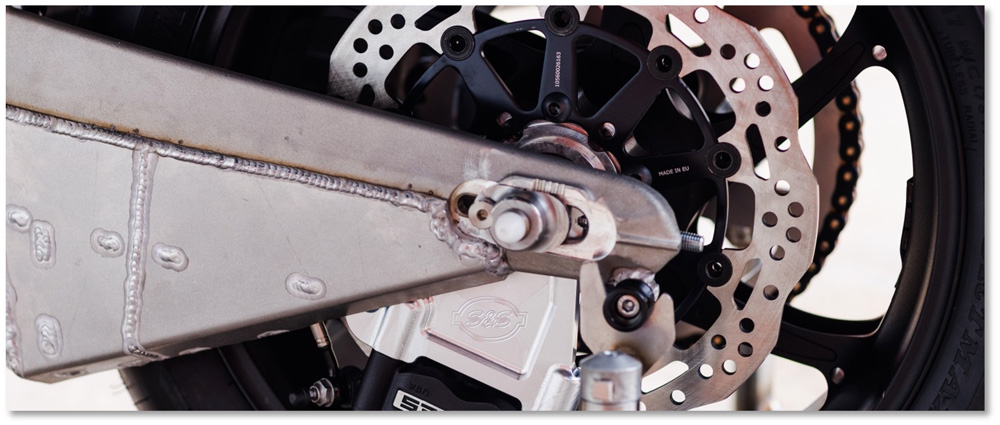

Finding and using the available grip is one of the keys to riding this, or any bagger for that matter, quickly, as is going way deeper under brakes than you think reasonable and slamming the chassis on its side. It’s a balancing game between the front and rear brakes, the latter of which has a massive Haynes four-piston caliper and front disc to help haul the Indian up, so there’s at least twice as much rear braking power on the race bikes as there is on a stock Challenger.

“You can carry 60° lean angle no problem, and you can run it around the corner at a huge rate of knots,” says McWilliams. “But, trying to make yourself learn that is quite difficult. Trying to convince yourself that you’re not going to lose traction when you’re at a 60° lean angle with the engine cases touching—it’s going to stick, it’s going to stick. Convincing myself that I could carry that entry speed was the hardest thing for me. Until you do that, you can’t really go fast on a bagger. That’s why Tyler is so good—he’s prepared to step outside those comfort zones.”

The agility of the bagger has to be experienced to be appreciated.

The agility of the bagger has to be experienced to be appreciated.

It’s hard not to look at the MotoAmerica King of The Baggers as the two-wheeled NASCAR, even more so when you open the gas and let that monster of a motor roar. This is by far the most masculine motor I’ve ridden in years, and its intake roar is something to behold.

“We’re really focused a lot on airflow,” says Bailey. “It’s mainly all top-end work. We create the camshafts, CNC-machined cylinder heads, and the 110mm big-bore pistons. We machined some rocker arms, too, just for the higher rpm limit. All four rocker arms are different and machined out of a solid chunk of steel. The intake manifold on these bikes is actually 3D-printed aluminum, which is kind of cool, and then the outer runner is plastic, and this joins up to the massive single 78mm throttle body we took from a Chevy V6 car motor that replaces the twin throttle body setup of the stock motor.”

S&S are understandably coy about giving any performance figures—we know it’s pumping out north of 170 horsepower—but it’s the tremendous torque that grabs you when you have the Challenger pointed in your desired direction of travel and you give the noise tube a solid twist.

The swingarm is a stock unit with heavy bracing.

The swingarm is a stock unit with heavy bracing.

Exiting the notorious turn 10 onto the back straight at Chuckwalla, the Indian pulls up the hill like a stream train that’s been fed too much coal. A lightened crank of unspecified weight, allowed by the rules in 2022, but, for 2023, has been mandated at 10 percent weight reduction over stock, sees the Challenger tearing towards its redline like a four-cylinder sportbike. But unlike the latter, which can reasonably expect a redline somewhere in the realm of 14-15,000 rpm, the Indian Challenger tops out at 7700 rpm on the AiM dash and datalogger.

As I’m charging up the hill towards turn 11 at Chuckwalla, the number-one bagger barking at the horizon, I’m reminded of the speed the Indian Challenger showed at Daytona, when O’Hara went from the back of the grid to the win on the line by blitzing past Harley-Davidson’s Kyle Wyman in a fashion that must have been a bit embarrassing for the Motor Company.

“At Daytona we came out and kind of gave them a little bit of a sucker-punch,” Bailey says. “We definitely found some horsepower over the previous year, but after Daytona, Harley came back in Atlanta and they had a higher horsepower package, but they weren’t confident in the reliability. So, they pulled that out and from there on we were evenly matched, maybe a little bit down in horsepower to them.”

It takes time to understand how much you can push the front end on the bagger. Weather conditions prevented us from running slicks.

It takes time to understand how much you can push the front end on the bagger. Weather conditions prevented us from running slicks.

This is not really something that can be readily exploited at Chuckwalla, with low revs in fifth gear the best you can hope for against the completely tapped-out nature of Daytona. But Chuckwalla, with its many long, low- to medium-speed turns, does have its advantage in that it allows the superb mapping of the ride-by-wire throttle to shine through. The connection between the right wrist and the rear tire is exceptionally smooth, especially given the inertia of such a massive motor wedged underneath me.

“We’ve been working with guys from Max ECU in the UK on the throttle response,” Bailey continues. But as opposed to a Marelli system or something where those guys are very on top of motorcycle throttle control, we’ve had to really develop our own throttle maps and everything ourselves with the Max system.”

McWilliams, who was originally brought in as a development rider but ended up doing the whole season with the factory S&S Indian team, remembers the first test at Jennings before Daytona.

“Jumping on the bike, it was a real wake-up call because it was the very first kind of roll-out they’ve had on it with all this extra horsepower and torque compared to the 2021 bike.

“We didn’t even have a throttle map. We were just running one-to-one. So, jumping on this with a one-to-one throttle map was quite an eye-opener, to say the least.

“We worked closely with the calibration guys. They quickly got a handle on how to transfer all that torque to the rear tire. Then over the day, we made such big steps in progress that I kind of wanted to come back and do some more. When you see the bike developing quickly it gives you some extra motivation.”

O’Hara with the spoils. King of The Baggers has become MotoAmerica’s most popular class in only three years.

O’Hara with the spoils. King of The Baggers has become MotoAmerica’s most popular class in only three years.

Chuckwalla’s turns also allow the factory Indian’s incredible turn speed and agility for such a big bike to be put on full display. Charging into turn one’s left kink and hard right, the Indian rips from upright on the brakes to on its side in an instant. O’Hara’s racer is loose compared to McWilliam’s more stable setup, but it’s not loose to the point of nervous. The chassis doesn’t so much as talk to you as it does scream at you, especially when everything gets flexy on those first few seconds when the throttle is picked up. However, you’re never in doubt as to what’s happening beneath you, and it’s a feeling I can only imagine is increased when running the real race-spec Dunlop slicks used in MotoAmerica.

It’s quite remarkable what Indian Motorcycle and, for that matter, what Harley-Davidson has achieved in creating the King of The Baggers class, because this has easily become one of the most popular classes not just in America but, judging from the YouTube numbers, around the world.

After riding Tyler’s and Jeremy’s bagger at Chuckwalla, I take my hat off to these men and women because although spectacular and oh-so-American, these are not easy machines to ride. Big, heavy, brash, these are bad-ass motorcycles, but I’m glad to have been given just a small glimpse into what makes them tick and just how trick they really are. CN

The 2023 King of the Baggers series kicks off March 10-11 at Daytona.