| March 5, 2023

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

“Radical” Ron

By Kent Taylor

It is 1970 and the owner of a certain Harley-Davidson Baja 100 couldn’t care less that his bike bears at least some resemblance to one of the most successful desert racers ever made. The fact that heavily-modified Harley 100’s were ridden to victory in Baja by well-known racers like Mitch Mayes isn’t worth a hill of Mexican jumping beans to him today. This little Italian-made two-stroke is at rest in a garage in El Cajon, California, about 100 miles north of Baja and its frustrated owner has given up, telling his 12 year-old neighbor, “if you can get it started, you can have it!”

After a little tinkering, some fresh gasoline and a few good pushes, a confident, curly-haired kid named Ron Turner has the bike running. “It never ran well,” Turner recalls today, “but it did run. I rode it in the hills near our neighborhood and I fell in love with motorcycles!”

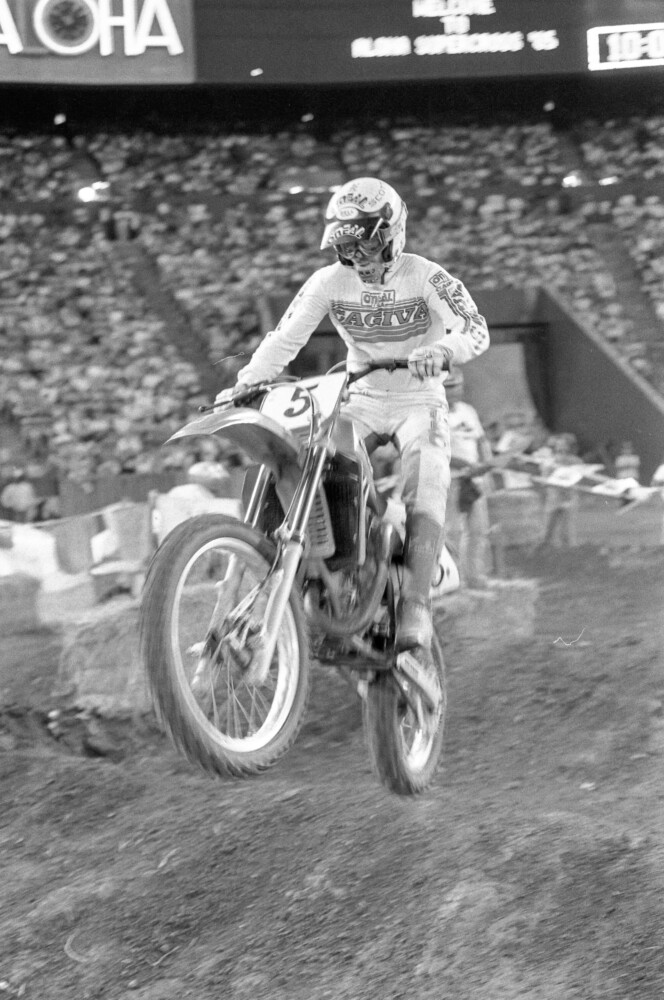

One of Ron Turner’s most memorable wins came at the CMC Aloha Supercross in 1985 while riding a Cagiva. Photo: Kit Palmer

One of Ron Turner’s most memorable wins came at the CMC Aloha Supercross in 1985 while riding a Cagiva. Photo: Kit Palmer

That Harley-Davidson 100 would be the first of many bikes that Turner would ride and repair, modify and make better. It would lead to a full-time position in research and development work in the industry and would also launch a successful California racing career; page flip through the local race results in 1970-80’s Cycle News archives and Turner’s name pops up like spring dandelions in a meadow.

Before the days of Loretta Lynn’s and home-schooled racers growing up in motor homes, the pathway to the fabled factory ride was marked quite clearly. It was a trail in SoCal and riders followed it from places like Saddleback Park and Indian Dunes to the offices of the Big Four distributors, located just a few miles away. Motocross’ history in the ’70s and ’80s was carved out in this area: Bob Hannah, Marty Smith, Donnie Hansen and Ricky Johnson were just a few of the many champions who cut their teeth on the sunbaked, hard-packed tracks of this region.

Ron Turner moved quickly through the motocross ranks. He graduated from his Baja Harley to a Yamaha AT-1 and after pleading with his mom, he entered—and won—his first motocross race in the beginner class. After four straight victories, the local promoter moved him to the intermediate class where, after another four straight victories, he was placed in the expert class. In fewer than 10 races, Turner found himself racing against the fastest riders in Southern California’s District 38. He earned a sponsorship ride from Don Vesco Yamaha. And then he met a young racer who had just founded his own motocross hop-up shop. The business was called the “Flying Machine Factory” and the owner’s name was Donnie Emler.

“Uncle Donnie told me that I if wanted to really make it big, I would have to move on to where the best riders were racing. He said, ‘you have to go to the CMC (Continental Motosport Club) and race against the really fast guys, guys like Mike Bell.’

“So, a week later, I went to a CMC race. Mike Bell was there, and I beat him!” Soon after, and not coincidentally, Turner picked up a new sponsor, FMF Racing. Forty-eight years later, Turner still refers to company owner Emler as “Uncle Donnie.”

Turner had developed a good working knowledge of what made a motocross motorcycle tick, which led to U.S. Suzuki hiring him for their R&D team. His office was the racetrack, and his business attire was full MX gear. He and fellow testers like Bob Elliot would put in 100 laps at Carlsbad—every day! “Nobody,” he states matter-of-factly, “has more laps around that track than me.”

“We were riding what were essentially the next year’s production bikes,” he says. “The Japanese engineers were there with stopwatches, timing us as we rode with different expansion chambers, shocks and so on. It was important work and once in a while even Roger DeCoster would show up to help.”

At the end of the testing, all the secret prototype bikes were locked away from inquiring eyes. But Turner’s day wasn’t done. In the 1970s, SoCal offered nighttime racing on weekdays, so Turner would head from Carlsbad to OCIR (Orange County International Raceway) on Tuesday, Ascot Park on Wednesday, back to OCIR on Thursday and then wrap up the week on Friday at Irwindale or Corona. The weekends would find him at Saddleback Park on Saturday and then back at Carlsbad on Sunday.

Turner was a local fixture in the Southern California motocross scene. He was a long-time test rider for Suzuki, and then Honda and Cagiva.

Turner was a local fixture in the Southern California motocross scene. He was a long-time test rider for Suzuki, and then Honda and Cagiva.

“Suzuki provided me with bikes and parts for the local races. I usually had nine motorcycles, two of each size and they would be set up differently for the different tracks.”

By his own personal account of his career in Southern California motocross, Turner won a staggering 974 races throughout the ’70s and ’80s. He would often enter all three pro classes (125cc, 250cc and Open) on the same day. On 13 occasions, he was victorious in all three classes. He was making a good living as a local pro, some days winning more than $800 in prize money. But getting rich on the local scene wasn’t Ron Turner’s dream. He wanted to be a National Champion, which was something his employer didn’t want.

“I don’t know why I didn’t get my chance at a factory ride,” he says. “Maybe they didn’t like my curly hair, or the fact that I usually just wore prescription sunglasses instead of goggles.”

“Suzuki told me that if I wanted to ride the Nationals, I was going to do it on my own,” Turner says. “I didn’t receive any help from them. In fact, they often tried to pressure me, telling me that I had to stay here in California.”

Undeterred, he headed for the road. While his results were good, with several top-three finishes in the 125cc class, Turner never got the call for the factory ride.

He competed on numerous brands in his career, including Suzuki, Yamaha, Honda and Cagiva, the latter of which he rode to a supercross victory at a non-AMA event in Honolulu. His professional racing days ended in the late ’80s.

“I don’t know why I didn’t get my chance at a factory ride,” he says. “Maybe they didn’t like my curly hair, or the fact that I usually just wore prescription sunglasses instead of goggles. Sometimes, it wasn’t just all about results. Some guys had big personalities and that’s how they got their sponsorships. That just wasn’t who I was…still isn’t.”

Would it have made a difference in his results? What if a factory team had given him a chance?

“I got to ride David Bailey’s Team Honda bike one time,” he says. “I was four seconds a lap quicker on that bike than on my production bikes. They were that much better than the stockers I had to ride.

“I know,” he adds, “I could’ve won a couple of national championships.”

Turner still lives in Southern California and works for a trucking company. CN