| December 27, 2022

Now held across the never-ending sand dunes of the Arabian Peninsula, the Dakar Rally has become one of the most eminent—and expensive to enter—motorsport events on earth.

Having collected $47m from the Saudis to host the Dakar for five years, the Amuary Sports Organization vacuums up an estimated $11 million annually in competitor and support crew fees, even charging the independent world media just to report from the Dakar bivouac (though the French caterers do run a half-decent buffet).

These amounts are insignificant compared to what the big bucks manufacturers cough up to support the event, to race loops around the empty wastes of a kingdom that has plowed $1.2 billion into sports sponsorship over the past few years.

Mason Klein crests one of the millions of dunes scattered on the Dakar Rally route in 2022.

Mason Klein crests one of the millions of dunes scattered on the Dakar Rally route in 2022.

It’s doubtful this is what Thierry Sabine envisaged when he experienced his near-death epiphany in the Sahara Desert way back in 1978. Shortly after which, 182 of Thierry’s mates became so enthused by his vision, the Paris to Dakar Rally Raid was born.

A peculiarly French phenomenon, the 1979 Dakar became a top rating TV success across snowbound Europe and, within three years, participant numbers doubled. These rally-raids became considerably longer and exponentially more difficult and, in 1986, the Paris-Dakar swung by Algiers in a grueling 9300 mile loop, resulting in an eighty percent DNF rate before reaching Dakar—the capital of Senegal.

The 10th anniversary of the Dakar attracted more than 600 participants, encouraging the ASO to capitalize on their investment. Bypassing Dakar altogether, the 1992 event crossed the Central African Republic, Chad, Cameroon and the Congo then, thanks to the marvels of GPS, more than fifty percent of the crews celebrated their success in Cape Town, South Africa.

Five years further on, entries had dropped to an all-time low. Many of the poorer African nations, annoyed at the wealthy dilettantes scattering their goat herds, were using the brightly colored racers for target practice, and theft around the remote bivouacs became a major problem.

Fabrizio Meoni scored KTM’s first victory in 2001, making it back-to-back wins the following year. The KTM 660/690 Rally proving so potent that, to stimulate interest in the motorcycle division, KTM supported two factory teams, the first in the electric blue of French manufactured Gauloises cigarettes, the second in the hot orange of the Spanish Repsol Oil Conglomerate. This annual ritual may have continued had not terrorists threatened to add a touch of excitement by placing a few improvised explosive devices along the Dakar route, thus underlining the end of the African era.

Matthias Walkner will be looking to add to his 2018 Dakar triumph in 2023.

Matthias Walkner will be looking to add to his 2018 Dakar triumph in 2023.

Come 2008, Argentina, Chile and Peru welcomed the ASO to South America with open arms and an open check book. Coupled with the advances in digital imagery, the television coverage of these landscapes stimulated armchair adventurers across the globe.

The move to South America also stimulated more interest from the USA, particularly when three-time National Hare & Hound Champion, and the then current Baja 1000 Champion, Kurt Caselli joined the fray.

Yet, at competition level, Dakar remained the Cyril Despres and Marc Coma show until the ASO reduced the moto capacity limit to 450cc in an effort to entice more manufacturers into the event.

Bolivia was the next target for the ASO, but the Bolivians quickly decided the economic benefits of contributing to the coffers of the ASO had limitations. Argentina and Chile also took a powder, leaving Peru to host the 2019 Dakar.

Gone were the extensive panoramic vistas, replaced largely by a vast sea of sand dunes comprising the shortest Dakar Rally on record. An event that heralded the cessation of KTM’s long held supremacy, along with the termination of the South American era.

Even though Covid was unknown outside of Wuhan, 2020 was a watershed year for the Dakar. The time was ripe for the Saudi Royal Family to decree Dakar would be incorporated into the oil rich Arabian Emirates, as hosts of the legendary event for the foreseeable future.

Ricky Brabec will be out for revenge in 2023 as he chases a second Dakar title.

Ricky Brabec will be out for revenge in 2023 as he chases a second Dakar title.

Dismissing the tradition of a long distance, linear cross-country rally, this modern era Dakar would become a series of intricately surveyed loops across the Arabian Peninsula. For the professional riders the advantage was that they’d be back in their campervans by sunset. For the also rans nothing would change, except that the Arabs they were likely to meet wouldn’t terminate their event with an AK47.

So, everything was the same, yet different. An expanding TV audience dictated a refined format, parity demanded tighter route instructions, and race strategy had taken precedence over rider skills. Le Dakar, along with the Indianapolis 500, the Le Mans 24 Hour, and the Isle of Man TT, had become one of the four most recognizable motorsport brands around the globe.

Headlined by American cross-country ace Ricky Brabec, Honda HRC took on the challenge in 2016 but, due to mechanical problems, regulation breaches and inexperienced teamwork, Brabec suffered a series of DNFs, despite demonstrating his skills with a number of Stage wins.

It all came together in 2020 when Ricky Brabec became the first American to win Dakar, presenting Honda with its first Dakar victory in more than thirty years. The Honda team backed up with a 1-2 the following year. Then in 2022, Sam Sunderland scored for GasGas. What was a little surprising was that the once indomitable KTM only just managed to scrape on to the podium for three successive years.

Can Joan Barreda hold it together to finally take a Dakar win?

Can Joan Barreda hold it together to finally take a Dakar win?

This is something KTM wish to rectify in 2023, if only to prove their unbeaten run of eighteen victories wasn’t simply due to lack of competition. Norbert Stradlbauer, Team Manager for Red Bull KTM, Gas Gas and Husqvarna, has the strongest line-up, with former winners Toby Price, Matthias Walkner and Kevin Benevides on KTM and current champion Sam Sunderland on GasGas. All are supported by an experienced second row, including Daniel Sanders, Skyler Howes and Luciano Benevides.

Honda HRC Team Manager, Ruben Faria, has a tighter knit team with Ricky Brabec, Pablo Quintanilla, Joan Barreda, Jose Ignacio and Adrien Van Beveren. Former winner Ricky Brabec is quietly confident.

“As a former winner, the pressure is not as great because I’ve been there before,” he said. “It looks like the 2023 route along the coast has something in common with 2020, an area that helped me a lot, with rocks and rough terrain, so hopefully we can finish on the top step.”

However, everyone will need to cope with the new regulations. For several years, the rider first off the start line suffered the disadvantage of being the first to navigate the route. Certainly, the following rider needed to be diligent with the route instructions, the third rider a little less so. However by the time the fifth rider roosted out, all that was required was to select the fastest line through the wheel tracks ahead. Now, with almost the entire event held across a windswept sea of sand, this inequity was compounded.

Sam Sunderland will be giving it everything to keep that number one plate.

Sam Sunderland will be giving it everything to keep that number one plate.

For 2023, to compensate the rider ‘opening the piste’ a time bonus will be awarded for the period spent leading the stage on the ground. The example provided explains that “if a previous stage winner leads out the following day they will be credited with 1.5 seconds bonus time for every kilometer they remain in the lead.” This credit will be deducted from the rider’s elapsed time for that stage.

All riders will now be provided with a digital road book. Yet, in the most radical development since the move to Saudi Arabia, the new regulations include randomly splitting route instructions, so all riders will not follow an identical route each day. Without doubt this will hinder the practice of following the leader to the various timing points but, at the same time, this attempt at parity is bound to create disputes over the relative difficulties of alternate routes.

All the pro teams profess to be conversant with the new regulations and a study of the official entry list provides no standout favorites, though current Dakar and World Cross-Country Champion Sam Sunderland, looks as though he’s ready to join the pantheon of all time Dakar legends with a third win.

Stars and Stripes

Klein goes into the Dakar one year wiser after his exceptional performance on the 2022 Dakar.

Klein goes into the Dakar one year wiser after his exceptional performance on the 2022 Dakar.

American participation in the Dakar is at an all-time high. Closely following Ricky Brabec will be Skyler Howes on a factory Husqvarna and 2022 Rookie of the Year Mason Klein, riding for the BAS KTM Satellite outfit. Then among 10 other hopefuls is a loosely knit team of rookies, riding under the banner of the American Rally Originals; each living out of their own 19-liter containers for 15 days sharing the chain oil. Good luck, guys!

Statistically Speaking

Adrien Van Beveren joins Honda after Yamaha pulled out of international rally competition.

Adrien Van Beveren joins Honda after Yamaha pulled out of international rally competition.

Joan Barreda Bort has already won almost double the number of Dakar Stage wins than any rider still competing. His style of win-it-or-bin-it could see him break the all-time record in 2023—as long as he remembers to stop and refuel. A victory for Toby Price or Sam Sunderland could see either rider move up to equal fourth on the Dakar Honor Roll. Or maybe Adrien Van Beveren could score the 23rd victory for France.

There’s No Disputing

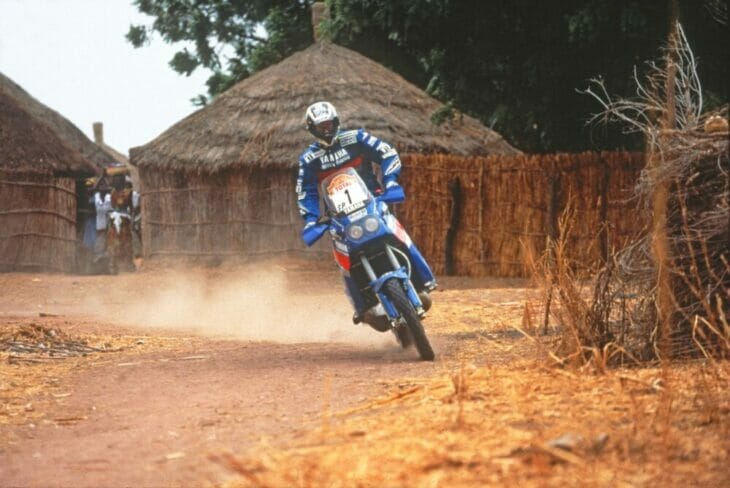

Stéphane Peterhansel back in the early days of the Dakar when he was almost unbeatable on his Yamaha.

Stéphane Peterhansel back in the early days of the Dakar when he was almost unbeatable on his Yamaha.

l’s position as G.O.A.T with six wins in seven years on his twin-cylinder Yamaha YZ850 Super Téneré. No future rider is likely to come close to Peterhansel’s record given the number of pro riders competing in the modern era. Peterhansel has also racked up victories for Mitsubishi, Peugeot and Mini Cooper, and driving for Audi, is one of the favorites to win the Auto Division in 2023.

Win On Sunday: Sell On Monday

Aussie ironman Toby Price is out for win number three on the Dakar.

Aussie ironman Toby Price is out for win number three on the Dakar.

While the KTM conglomerate and Honda HRC continue to pour millions into their respective Rally Teams around the globe, 2023 marks the first time in Dakar history that Yamaha have not had an official presence in the moto division. With nine outright victories and 140 forty Stage wins, Yamaha has enjoyed more success than BMW, Husqvarna, Suzuki, Cagiva and Sherco combined. Not forgetting Kawasaki and Hero with a single Stage win apiece.

Peter Whitaker