Kit Palmer | August 14, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

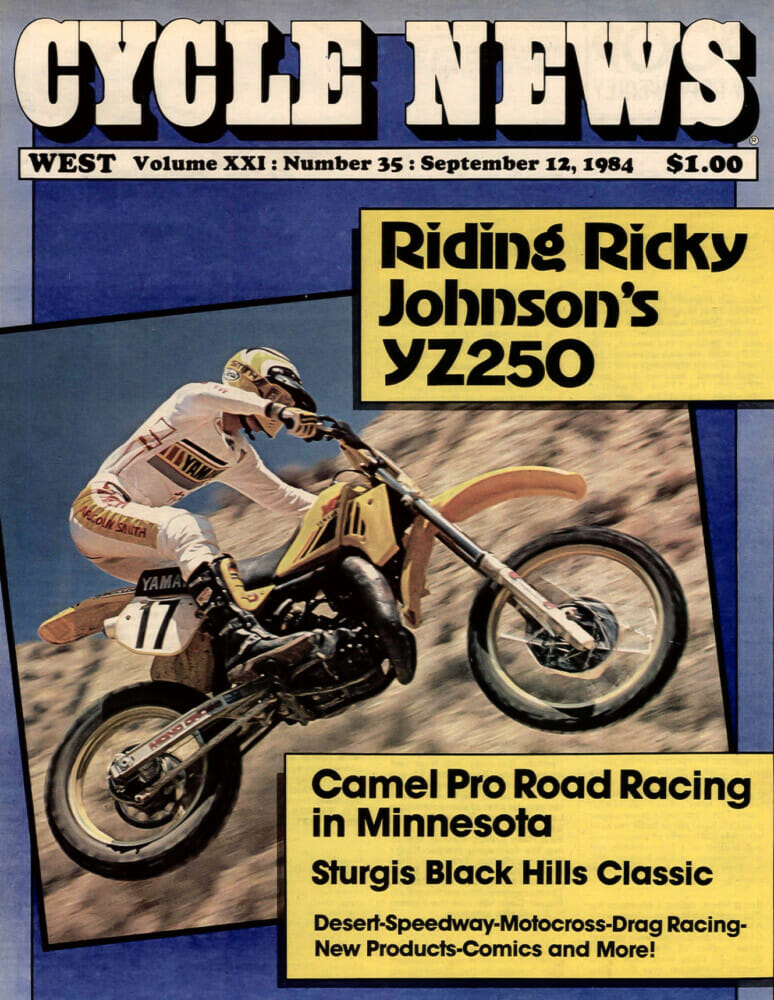

Riding RJ’s Yamaha

In my nearly 40-year tenure in the magazine business, I’ve been fortunate to ride a wide variety of motorcycles, but I’ve never ridden an honest-to-goodness “works” motocross bike. In the day, mainly throughout the 1970s, it wasn’t all that unusual for magazine editors to get the chance to test a factory rider’s works bike. I’ve ridden the same motorcycle as a famous pro a few times but never a true works bike. That’s mainly because works bikes were banned in 1986, just a few years after I landed a job here at Cycle News, so my window of opportunity to ride a works bike was essentially slammed shut and locked before I got the chance. However, I did come close to riding one once while works bikes were still legal.

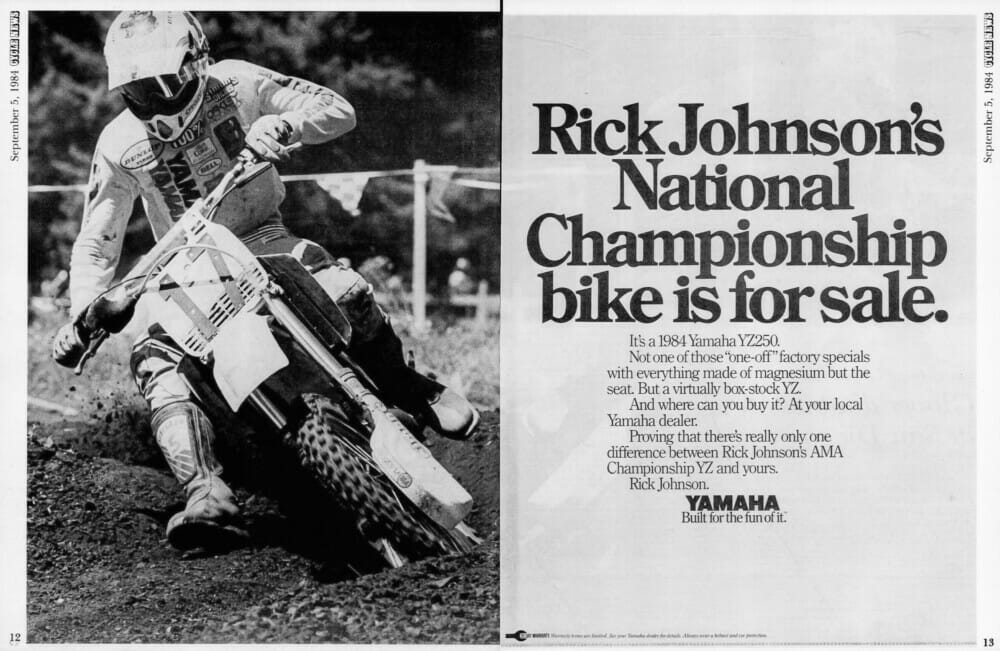

Yamaha wanted to prove just how production its “works” YZ250L was, so, just days after the bike had won the 1984 AMA National Motocross title with Ricky Johnson, Yamaha let us ride it.

Yamaha wanted to prove just how production its “works” YZ250L was, so, just days after the bike had won the 1984 AMA National Motocross title with Ricky Johnson, Yamaha let us ride it.

In the early-to-mid 1980s, there was already talk of a “production rule” which would ban high-dollar and high-tech factory works bikes from competing on the AMA circuit, both indoors and out. The idea was to make racing more competitive by closing the technology gap between the factory race bikes and the production bikes that the privateers—who made up the heart and soul of the sport of motocross—had to ride. Plus, it would reduce costs for the factories. With the production rule in place, the factory boys would have to start out with the same motorcycle that Johnny Racer could buy right off the showroom floor. Whether or not the production rule was a good or bad idea is still up for debate, and I’m not going to get into that today.

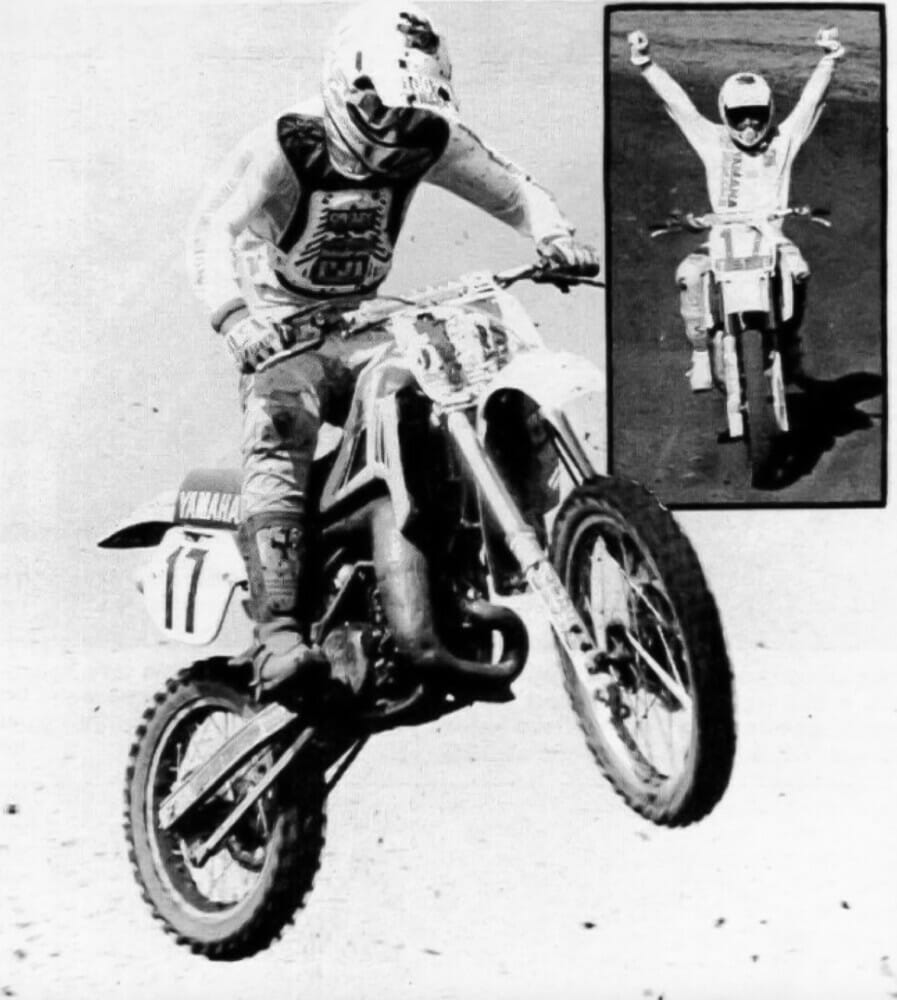

In the early ’80s, Yamaha figured the production rule was coming and, instead of waiting, chose to get a head start on their competitors. Yamaha Racing Manager Kenny Clark announced that its factory race team would start riding production-based bikes starting with the 1984 season. (The production rule went into effect in 1986.) Yamaha team rider Ron Lechien said, nope, that’s not what I signed up for, and high-tailed it to Honda, and wouldn’t you know it that Lechien and Yamaha’s Rick Johnson would battle back and forth for the AMA 250cc National Motocross title that year (’84). It was production-based versus works, and guess which won? Production-based. By just eight points.

Johnson wrapped up the 250cc title at Washougal, finishing just eight points ahead of Ron Lechien, who rode a true “works” Honda.

Johnson wrapped up the 250cc title at Washougal, finishing just eight points ahead of Ron Lechien, who rode a true “works” Honda.

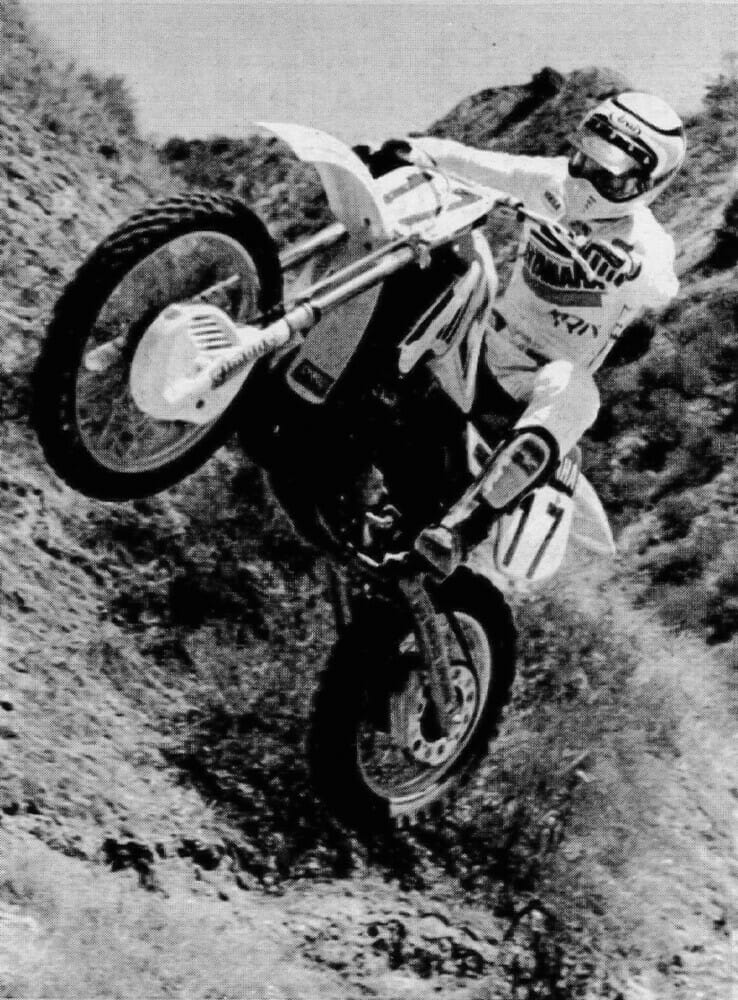

Four days after Johnson clinched the 250cc MX title at Washougal, I found myself cutting laps at DeAnza Cycle Park in Southern California on the very same YZ250L that Johnson had won the title aboard. I was the first person to ride it after Johnson crossed the finish line. In fact, the bike still had Washougal dust and dirt on it. It was as though Johnson’s mechanic Cliff Lett had loaded the bike up at Washougal and drove it straight to DeAnza, which I think pretty much happened.

Of course, Johnson’s YZ was far from stock, but it was indeed production-based. Some parts were carried over from Johnson’s previous works bike but they were parts you and I could purchase at our local Yamaha dealership, such as a YZ60 ignition Johnson liked for its heavier flywheel. Depending on the track, Johnson would swap out entire transmissions from the 1982 or ’83 stock YZs. The front brake, however, was suspiciously works—it was a disc that would later find its way onto the production YZ250. For the most part, every modification performed to Johnson’s bike was revealed in the company’s Wrench Reports that were regularly mailed to all YZ owners.

I was most impressed with the bike’s motor. Going in, I was expecting it to have so much power I wouldn’t be able to hold on to the handlebars or be so explosive that my arms would turn into cooked spaghetti after a lap. I could not have been more wrong.

I wrote: “The most impressive aspect of the motor wasn’t the top speed, but the strong and smooth powerband. It hooked up well and was very predictable.” Not what I was expecting from a championship-winning motocross bike, for sure. It was faster than a stock YZ250 but way more rideable from top to bottom. Back then, two-stroke MX bikes had the tendency to be either all bottom-end, all midrange, all top-end, or a slight mixture of the two (bottom/mid or mid/top). This bike, however, had it all. To this day, I remember it as being amazing. This was partly due to a long-rod kit, a custom Stuart Toomey-built exhaust pipe installed, and many other smaller hand-made tweaks performed throughout the engine, including cylinder porting, carburetion mods, and so on. Again, all these tricks Johnson and Lett devised were revealed in Yamaha’s Wrench Report. Yamaha was adamant—no secrets. Well, sort of. The YZ60 ignition trick was a bit of a secret because Yamaha just didn’t have enough of them to go around. “It was a word-of-mouth thing,” Lett said. “But if anyone asks, I’d tell them.”

Win on Sunday, sell on Monday suddenly seemed more of a reality.

Win on Sunday, sell on Monday suddenly seemed more of a reality.

However, despite the great motor, I found Johnson’s bike to be nearly unrideable. The culprit? The stiff forks. I just couldn’t comprehend how any human could ride a motocross bike with forks set up as stiff as Johnson’s. “Stiff doesn’t really describe how they feel—it’s more like rigid,” I wrote. I said they “felt as though they had two inches of travel instead of 12.” Lett agreed with me and said Broc Glover and Keith Bowen, Johnson’s teammates at the time, ran much softer forks. Lett said Johnson likes them this way so he can “really push the bike through rough terrain and over huge whoop as hard as he can, and he doesn’t like the front end to dive when entering turns.”

I tried to ride like that at DeAnza that day, but it didn’t work for me. To give you an idea of how stiff Johnson’s forks were, the stock YZ250L came stock with .300 fork springs. The optional heavy-duty .325 spring was considered extremely stiff. Johnson used .375 springs.

Stiff forks took on a new meaning after riding Johnson’s YZ250.

Stiff forks took on a new meaning after riding Johnson’s YZ250.

The rear suspension, however, was way more in line. In fact, I could quickly tell that it was better than the stock suspension, which was overly soft and springy off the showroom floor. Johnson’s rear suspension felt much firmer and just flat-out better, even though Johnson outweighed me by approximately 20 pounds. Still, improved rear suspension didn’t make up for the insanely stiff forks that, I must admit, ruined the experience of riding a factory race bike for me.

I concluded my article by saying I was bummed because Johnson’s bike didn’t turn me into a national-caliber rider, but I did have fun trying. Since then, I’ve ridden a few factory bikes and discovered Johnson isn’t the only top-level racer who likes their forks ridiculously stiff. They pretty much all do. So, if I ever get to ride a factory motocrosser again, I’ll do what the pros do—bring my own forks. CN