Larry Lawrence | August 7, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

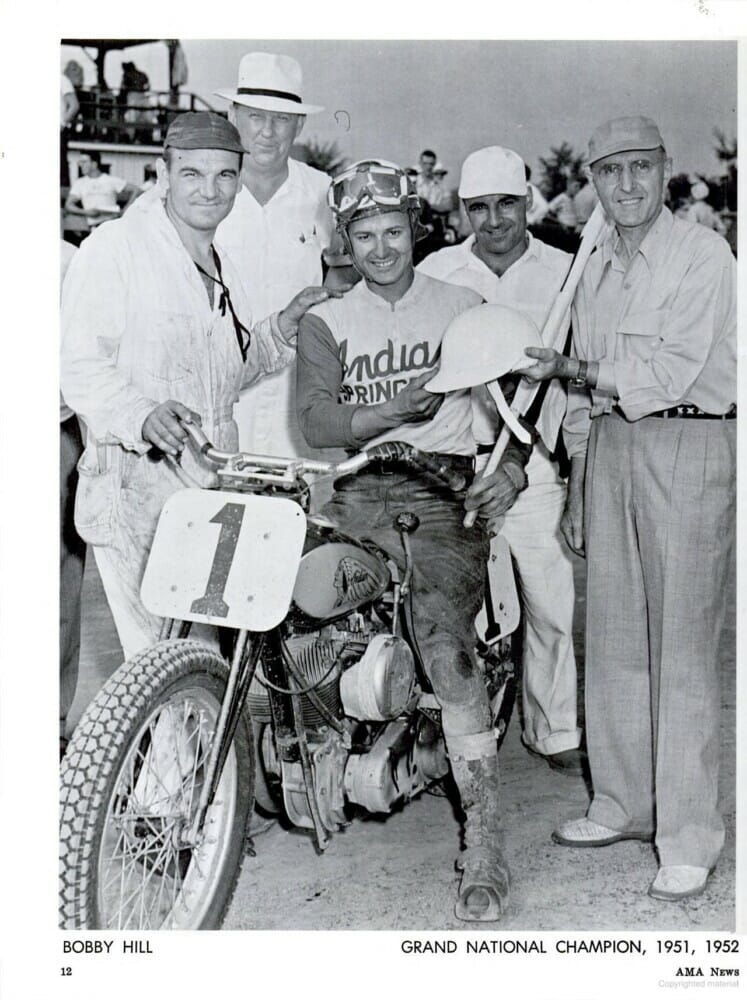

Bobby Hill, the two-time AMA National Champion of the early 1950s and Daytona 200 winner in 1954, passed away July 12. He had just reached 100 years old four days earlier.

Bobby Hill was part of both the Indian and BSA Wrecking Crews. Bobby is pictured here at the BSA celebration at Daytona in 2004. Photo: Larry Lawrence

Bobby Hill was part of both the Indian and BSA Wrecking Crews. Bobby is pictured here at the BSA celebration at Daytona in 2004. Photo: Larry Lawrence

It’s absolutely stunning that Hill became a centenarian. After all, Hill raced in the 1940s and ’50s in an era when the sport was hazardous compared to today. He once told me that many races he ran didn’t even have haybales covering the outside railings at big flat tracks. And then also, consider that Hill served as a Marine in World War II and saw action in areas with some of the most intense battles, such as the Philippines. He was a mechanic who worked on military planes, and the airports where he was stationed were often major targets for Japanese bombing. And to top it all off, Hill’s day job for years was driving a gas tanker! I don’t know what kind of lucky charm Hill had with him, but he certainly lived a long and rich life.

Bobby was a racer everybody liked. He was soft-spoken and had a subtle sense of humor. He also had great stories of his racing days and loved to share them.

His likeability was evident in 1951 when Hill won the prestigious and highly coveted AMA’s Most Popular Rider Award.

Hill was born in 1922 in the West Virginia northern panhandle town of Triadelphia. The National Road ran through Triadelphia and was a busy thoroughfare in the 1930 and ’40s, so a young Hill was exposed early to various motorized transportation modes, including motorcycles. When he was still a teenager, Hill’s older brother started working at a Harley-Davidson dealership, and when he was just 14, Hill began riding motorcycles for the first time. Hill was always proud of his West Virginia roots, even though he moved to the Columbus, Ohio, suburb of Grove City in his early 20s so he could be closer to the bulk of Midwestern race tracks.

Hill won the AMA National Championship twice in the early 1950s. Back then, the winner of the Springfield Mile was crowned national champ.

Hill won the AMA National Championship twice in the early 1950s. Back then, the winner of the Springfield Mile was crowned national champ.

I last visited Hill and his wife Nancy at their immaculate home in a quiet and well-kept Grove City neighborhood in 2017. One of Hill’s neighbors, Clay Powell, noted at the funeral home memory wall: “Many people knew Mr. Hill as a motorcycle champion, but to us, he was ‘Bobby,’ the guy who was a wonderful person, neighbor and one who was meticulous about his house which helped make the whole neighborhood look great.”

Hill’s wife Nancy passed away last year. They were very close. Often you hear of a spouse dying not long after the other; this was certainly the case with Bobby and Nancy.

Hill was basking in the glow of renewed attention late in life, brought on by a revival of Indian Motorcycles and the company’s entry into American Flat Track racing. Hill and Bill Tuman were surviving members of the last of Indian’s Wrecking Crew from the mid-1950s before the original Indian went bankrupt. Tuman passed away late in 2020. He was 99. Bill and Bobby were Guests of Honor when Indian unveiled its FTR750 race bike at Sturgis in 2016.

“I think it’s wonderful that the new Indian remembered us,” Hill said. “It was a great feeling for Bill and me to go to Sturgis and see the appreciation we got from the riders and all the fans. I’ve got to tell you, it’s tough just living day to day at my age, so those kinds of moments—to see that we haven’t been forgotten—well, it’s really something special.”

Bobby bought his first motorcycle at 16, a shiny new 1938 Harley-Davidson WLD. It was a rare machine. Only about 300 were made. He joined the local Wheeling Roamers Motorcycle Club and soon participated in club meets. Hill grinned when he told me about the Sunday rides and hanging out with his buddies in the club.

“There was a lot of bold talk but very little action,” he said. “All my buddies bragged about how fast they were and how they were going to go racing, but of all the guys in the club, I was about the only one who actually went through it.”

Hill was a fan of racing before he became a racer. He and his buddies would ride to Ohio to watch races, and Hill said he became a big fan of Ed Kretz Sr., Jimmy Chann, Billy Huber, Chet Dykgraaf and Leo Anthony. Some of those guys he’d never seen race in person but only read about. Little did he know at the time that he’d be racing against many of his heroes in a few years.

Hill started racing in 1940, shortly before World War II brought racing to a halt. After serving in the Marines, Hill, like many motorcyclists, was eager to return to riding after the war. With his racing experience before the war, the AMA allowed him to become an expert. Hill nearly won his first pro race, the 1947 Daytona 200. Riding an Indian, he gradually worked his way through the field. With about 50 miles to go, he was in second place.

Hill won his first national in 1948 at Lakewood Park in Atlanta but had to share the victory with Billy Huber in the only official tie in AMA National racing history.

Hill won his first national in 1948 at Lakewood Park in Atlanta but had to share the victory with Billy Huber in the only official tie in AMA National racing history.

Hill describes what happened from there: “I could see Johnny Spiegelhoff [the eventual winner] ahead of me, and I was gaining. I kept getting a pit signal from my crew that read ‘P2.’ I thought they were telling me I was in second place. As it turns out, I was really in the lead since we started by rows back then five seconds apart and were timed. Even though Spiegelhoff was in front of me, I was actually about 15 seconds in the lead. I didn’t know that, though, and I was riding as hard as I could to catch Spiegelhoff. At about the 180-mile mark, I came flying into the south turn and pitched the bike in hard. Two slower riders were going through the turn, and I just drifted out wide and hit one of them, and lost my rear brake lever. I came into the north turn and thought I had slowed down enough, but apparently, I didn’t, and I crashed out of the race.”

He came so close to victory in his debut but would end up waiting until the next season to earn his first national win, and it was a unique one, to say the least.

It was August 1948, and the site was the Lakewood Park Mile in Atlanta, Georgia. It was the AMA 10-Mile National, and the race came down to Hill and one of his racing heroes Billy Huber.

“Being such a new expert rider, I didn’t know much about drafting,” Hill said. “Billy sure did, though, and he drafted right behind me and, at the last possible moment, zipped underneath me, and we crossed the finish line side by side.”

The massive sold-out crowd went nuts as the two crossed the finish line. AMA officials quickly huddled to compare notes to determine who came out on top. Heads shook, and finally, the judges declared the race a dead heat. Mike Benson, president of the fair, announced that both riders would receive first-place money. More cheers greeted the announcement.

“We both got the same money, but Billy got the trophy,” Hill recalls. “Back then, there was a little prejudice [favoring] Harley riders, and they gave it to him. Three or four months later, they made up a duplicate trophy and gave it to me.

“That race pushed the AMA to get a better system to decide finishes. Up to then, they just had a referee standing at the line to call the finish. I think they eventually got high-speed cameras. After that race, I always looked under my arm a little bit coming out of the last turn.”

After winning the national title in 1951 and 1952 by way of the winner-take-all Springfield Mile, Hill finally earned a victory in the Daytona 200 on his eighth attempt in 1954 riding a BSA. Since the AMA Grand National Championship Series was inaugurated in ’54, his Daytona victory earned Hill the honor of winning the first-ever AMA Grand National Series race.

In 1959 Hill decided to retire. He said he could still finish consistently in the top five at most nationals, but a newer generation of riders like Carroll Resweber, Brad Andres Dick Mann and Dick Klamfoth was taking over. Hill was 37 at that point and felt it was time to focus on family and career. He stayed involved by building engines for other racers well into the 1960s.

There was a period in the 1970s and ’80s where Hill said he and many of his fellow riders from the 1940s and ’50s seemed to be forgotten. It was an exciting period in racing of new machines and races, television coverage, and more significant money. But then, in the 1990s, a period of looking back on the sport’s history began. Spurred on by popular television announcer Dave Despain, who often featured these old champions on TV and events he helped promote, along with the AMA forming the Motorcycle Hall of Fame, and generally just a newfound interest in vintage machines and the men who raced them, brought Hill and other riders of his generation back into the spotlight.

During the AHRMA event at Daytona in 2004, Hill was part of a contingent of riders brought back to honor BSA’s racing heritage in America. With hundreds of fans seeking autographs and the interview sessions where these guys got to relive racing stories of their youth, you could just see the joy on their faces. Like Bobby told me years later, “It was wonderful to find out that the current generation of motorcycle people didn’t forget us after all. We were fortunate to have the opportunity to come back and see the appreciation of the fans one more time.”

The family said that donations may be made to the Daytona 200 Monument to honor Bobby’s memories. For more information, visit www.daytona200monument.com. CN