Larry Lawrence | July 10, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

When Worlds Collide

Looking back on the history of professional motorcycle racing in America, the 1971 season stands out for many reasons. At that very moment, motorcycling, like the country itself, was going through major upheavals and transitions. Old traditions and ways of doing things were being questioned on a grand scale. That year would produce new forms of technology and geopolitical maneuvers that would have effects that continue to influence the world to this day.

1971 marked a turning point in the Vietnam war. The Pentagon Papers were published, showing that the American public was lied to about the war. The largest ever anti-war demonstration took place in Washington D.C. in April, with a half-million participants, showing America’s tolerance for the war was growing thin. Ping-Pong diplomacy opened relations between China and the U.S. Soon after that, the United States eased trade and travel restrictions with China. The world’s first microprocessor was released by Intel, which helped usher in the age of computers. And the first e-mail was also sent in 1971.

Similar turning points were happening in American motorcycle racing. For decades AMA Grand National racing ruled the roost, to the point that there really was only one recognized American motorcycle racing champion at that time, and it was the rider who won the AMA Grand National Championship. But now, motocross was sweeping America through the Trans-AMA and Inter-AMA Championships, which brought many of Europe’s motocross stars to compete with Americans. In 1971 things were still developing in American motocross. U.S. Champions were crowned, but they were simply the top scoring Americans in the Trans-AMA and Inter-AMA Series and normally well down the list in the overall rankings. That, too, was about to change a year later when the AMA launched its own National Motocross Championships.

Many considered Dick Mann to be the “old man” of the circuit and past his prime. But on the strength of his road race and TT performances aboard a factory BSA, Mann surprised everybody and won the 1971 AMA Grand National Championship. Mann edged out 1970 champ Gene Romero, who raced for Triumph. But in ’71, youngsters like Mark Brelsford, David Aldana, Jim Rice and a brash Junior out of Modesto, California, named Kenny Roberts, were on the rise.

Dick Mann was 37 in 1971, but he was still very competitive, especially on the road course. He won that year’s AMA Grand National Championship.

Dick Mann was 37 in 1971, but he was still very competitive, especially on the road course. He won that year’s AMA Grand National Championship.

Road Racing was also becoming a more significant part of the overall American motorcycle racing landscape in ’71. The Brits still essentially ruled the roost, yet the Japanese makers, with a history in Motorcycle Grand Prix racing, started putting more resources into the road racing side of the AMA Grand National Championships. Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki were all developing ever more competitive road race machines. And it was on the road courses of America where worlds were colliding, which will be the focus of our journey back to 1971.

It was the waning days of Milwaukee muscle in road racing. Harley-Davidson’s XR750 had been launched in 1970, but in ’71, Harley was still running the early iron-head version of the XR, and the bike was underpowered and prone to overheating. BSA and Triumph were running powerful inline triples with a good mix of speed and handling. Yamaha had yet to come out with the game-changing TZ700/750, and they were still contesting the road race Nationals with a sweet-handling and speedy TR-2B, a 350cc twin-cylinder two-stroke. Suzuki had the heavier TR500 500cc air-cooled two-stroke twin, and Kawasaki, like the Brits, were on the three-cylinder bandwagon, but being 500cc two-strokes, they were a very different beast. Blazingly fast, the Kawasaki two-stroke triples were temperamental, prone to seizing, and guzzled fuel at an alarming rate.

The opening National road race in ’71 at Daytona featured a massive factory presence.

“I can’t think of a year when there were more factory riders in America or anywhere than 1971,” said Don Emde, who raced for the BSA factory team that year. “Just our BSA/Triumph team had 10 riders at Daytona. Dick Mann, David Aldana, Jim Rice, Mike Hailwood, and me on BSAs, plus Gary Nixon, Gene Romero, Don Castro, and Tom Rockwood and Paul Smart on Triumphs.”

Kawasaki, too, had a massive Daytona effort headed by factory riders Ralph White and Yvon Duhamel, as well as a slew of factory-supported machines for Mike Duff, Cliff Carr, Walt Fulton, Dave Smith, Ginger Molloy, and Rusty Bradley (who tragically died after an early-race crash in the 200).

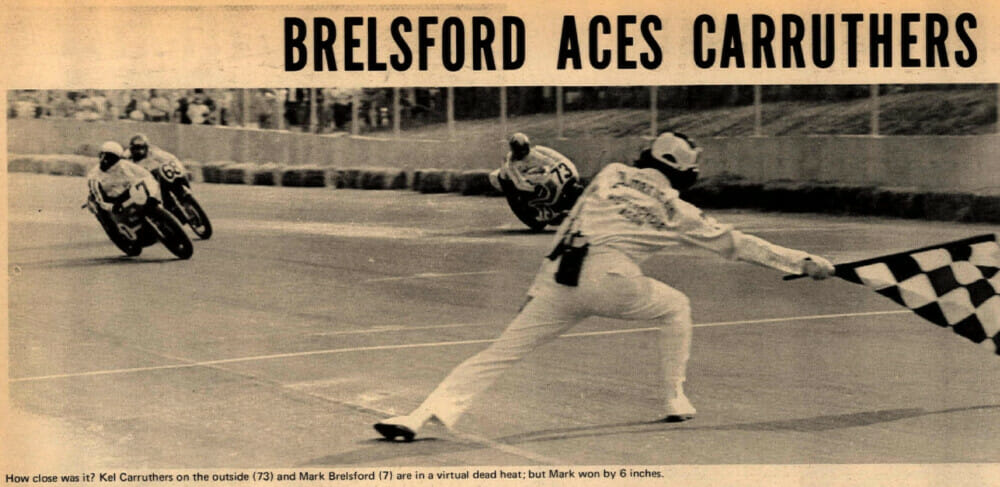

Kel Carruthers (73) rode the smallest bike in the Nationals in 1971 with his factory Yamaha 350. His acceleration disadvantage cost him. He lost three road races by mere inches, here losing to Harley’s Mark Brelsford at Loudon.

Kel Carruthers (73) rode the smallest bike in the Nationals in 1971 with his factory Yamaha 350. His acceleration disadvantage cost him. He lost three road races by mere inches, here losing to Harley’s Mark Brelsford at Loudon.

Instead of big factory efforts, Yamaha’s focus was on its factory support team of Don Vesco Yamaha, with Kel Carruthers riding a Yamaha TR2-B, backed by a large contingent of privateer entries.

Suzuki had Ron Grant, Jody Nicholas, Art Baumann, Ron Pierce and Geoff Perry.

Harley-Davidson also had a considerable factory effort with Cal Rayborn, Mert Lawwill, Mark Brelsford, Rex Beauchamp and Dave Sehl, along with a gang of other Harley-backed riders like Larry Darr, Larry Schaefer, Ron Widman and DeWayne Keeter.

If you’re keeping count, that’s at least 33 factory or factory-backed riders in the ’71 Daytona 200. If you add in the gaggle of riders getting Yamaha support for the race, you were well over 40 riders getting at least some form of factory assistance in the race.

Smart won the pole on a Triumph Trident, while the Harleys of Rayborn and Brelsford were second and third. Emde and Hailwood rounded out the front-row starters.

Approximately 38,000 fans showed up on race day and witnessed rookie Gary Fisher surprise everyone by taking the lead on his Krause Honda CB750-based racer. Fisher’s bike broke early, putting “Mike the Bike” Hailwood into the lead, followed by Smart, Rayborn and Mann. A broken transmission dropped Rayborn, Harley’s main threat, out of contention. Hailwood and Smart battled up front, swapping the lead, with Mann playing it typically conservatively in third, within sight of the leaders. The torrid pace set by Hailwood and Smart cost them. Both riders dropped out with engine problems leaving wily veteran Mann in the lead. Mann cruised to victory over Romero and Emde, giving the British triples a clean sweep of the podium.

The following month at Road Atlanta, Kel Carruthers made history by giving Yamaha its first “big bike” National victory. Carruthers put on a master class, biding his time and preserving his bike in the early going before taking over the lead from Harley’s Rayborn, getting a quick pit stop and pulling away to a dominating victory over Mann and White. Interestingly, Carruthers, at 33, was the youngest rider on the podium, with Mann 37 years old and White 36.

Mark Brelsford showed the iron-barrel Harley XRTT could be competitive when it lasted. In front of 28,000 fans at Loudon, Brelsford gave the iron XRTT its only National road race victory in a thriller when he out-drag-raced Carruthers’ Yamaha out of the final corner to win by about six inches. And how’s this for brand diversity? At Loudon, the top five finishers were all on different brands: Harley, Yamaha, BSA, Kawasaki and Triumph!

Dick Mann was the first rider in ’71 to score a second road race National victory after taking the top spot in Kent, Washington. He had a fierce battle with Kel Carruthers. Perhaps the biggest story coming out of Kent was that several riders, including defending series champ Gene Romero, were caught using forged medical paperwork for their racing licenses. The 15-day suspension sidelined Romero for the Ascot TT. He still came back to lead the championship for much of the middle of the season.

At Pocono in August, Mann won yet again on his BSA and took over the points lead in the process. Frustratingly for Carruthers, it was yet another race where he was virtually side by side with the leader coming out of the last corner, but the low-end grunt of the BSA meant that Mann was able to power to the finish line just ahead of Carruthers. Yvon Duhamel was clearly the fastest rider on the track at Pocono, but his thirsty Kawasaki triple caused him to take two fuel stops to the single pit stops of the other teams.

A variety of brands were competitive at the National road races in ’71. BSA, Yamaha, Harley-Davidson and Kawasaki all won road races, while Triumph and Suzuki also earned podium finishes. Here Jody Nicholas leads the pack at Loudon riding a Suzuki.

A variety of brands were competitive at the National road races in ’71. BSA, Yamaha, Harley-Davidson and Kawasaki all won road races, while Triumph and Suzuki also earned podium finishes. Here Jody Nicholas leads the pack at Loudon riding a Suzuki.

It finally all came together for Duhamel and Kawasaki at a hot and humid Talladega in early September. After three seasons of coming so close, the friendly French Canadian scored the victory on the Superspeedway by way of blazingly fast pit stops. He still had to make one extra stop than the rest of the contenders, but the team had gotten the refueling down to under five seconds! Duhamel finally claimed the $10,000 prize for giving Kawasaki its first AMA National victory.

The final road race of the season was also the final round of that year’s championship. It was the first AMA National at the newly completed Ontario Motor Speedway. Ontario that year was arguably a bigger motorcycling event than Daytona. The race, called the Champion Spark Plug Classic, featured the biggest purse in AMA racing history and that attracted world-class riders like Phil Read, Barry Sheene, Rod Gould and John Cooper. Read and Gould ultimately ended up not racing since their bikes were not ready or hadn’t been homologated before race weekend.

The 250-mile event was run in two 125-mile segments. A great crowd of 33,000 showed but rattled in the 150,000-seat facility. In the first leg, Duhamel and Nixon battled back and forth. The difference was fuel mileage. Nixon could go the entire 125 miles without a fuel stop, while Duhamel had to pit. Nixon took the win, Cooper was second on a factory BSA and Carruthers third.

In the second segment, it was Nixon leading early before crashing in oil in a turn. The oil collected many of the leading contenders and caused them to pit for repairs. Cooper somehow made it through without going down and led, only later to be passed by Romero, who was riding the wheels off his Triumph trying to win the series championship. Unfortunately, a broken throttle cable cost Romero any opportunity he had for the win and, ultimately, the championship.

The race came down to Cooper and Carruthers. The two swapped the lead numerous times in the closing laps. Carruthers led coming out of the final turn, but almost predictably now, Cooper’s BSA 750cc Triple had the power advantage, and he passed Carruthers just before the line. That gave Cooper the overall victory and the $14,500 prize money (about $106,000 in today’s money).

The following year things changed drastically. The British companies were suffering, and racing budgets were slashed, leaving just a couple of factory rides remaining. The days of dozens of factory and factory-supported riders were gone, only briefly to return in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The ’71 season certainly marked a turning point in the motorcycling industry. The British and American bikes were waning, and the Japanese brands were on the rise, on the track, and in the showroom. CN