Rennie Scaysbrook | July 14, 2022

Rennie finally realizes his greatest racing goal of racing the Isle of Man TT, but it was far more than just a few quick laps of the TT Mountain Course.

Click here to read 2022 Isle of Man TT | Part 1 online or in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

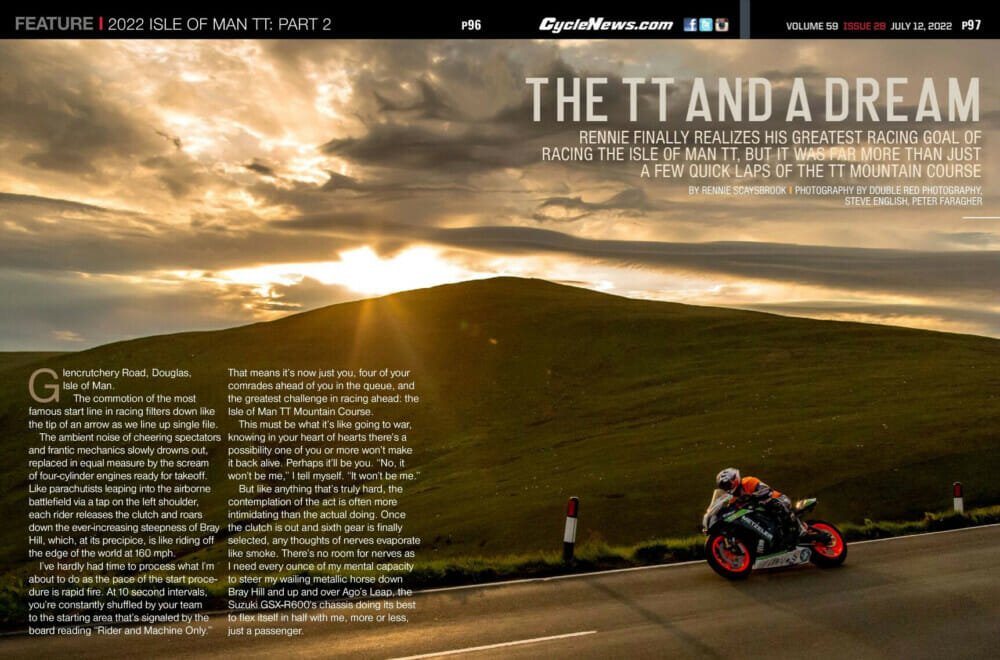

On a perfect summer’s night, ripping across the most famous mountain in motorcycle racing. This is what dreams are made of. Rennie is captured here beautifully by Steve English.

On a perfect summer’s night, ripping across the most famous mountain in motorcycle racing. This is what dreams are made of. Rennie is captured here beautifully by Steve English.

Photos by Double Red Photography, Steve English, Peter Faragher, Barry Clay, IOMTTPics.com

Glencrutchery Road, Douglas, Isle of Man.

The commotion of the most famous start line in racing filters down like the tip of an arrow as we line up single file.

The ambient noise of cheering spectators and frantic mechanics slowly drowns out, replaced in equal measure by the scream of four-cylinder engines ready for takeoff. Like parachutists leaping into the airborne battlefield via a tap on the left shoulder, each rider releases the clutch and roars down the ever-increasing steepness of Bray Hill, which, at its precipice, is like riding off the edge of the world at 160 mph.

I’ve hardly had time to process what I’m about to do as the pace of the start procedure is rapid fire. At 10-second intervals, you’re constantly shuffled by your team to the starting area that’s signaled by the board reading “Rider and Machine Only.” That means it’s now just you, four of your comrades ahead of you in the queue, and the greatest challenge in racing ahead: the Isle of Man TT Mountain Course.

This must be what it’s like going to war, knowing in your heart of hearts there’s a possibility one of you or more won’t make it back alive. Perhaps it’ll be you. “No, it won’t be me,” I tell myself. “It won’t be me.”

But like anything that’s truly hard, the contemplation of the act is often more intimidating than the actual doing. Once the clutch is out and sixth gear is finally selected, any thoughts of nerves evaporate like smoke. There’s no room for nerves as I need every ounce of my mental capacity to steer my wailing metallic horse down Bray Hill and up and over Ago’s Leap, the Suzuki GSX-R600’s chassis doing its best to flex itself in half with me, more or less, just a passenger.

Over the second jump at Ago’s at close to top revs in sixth, I flash past the big white house on the left and dart into the shade. Then, it’s hard on the brakes for Quarterbridge, where the madness of the past 15 seconds or so is replaced by a serene first-gear, right-hand cruise for three seconds or so, before I’m back on the throttle and pointing the motorcycle towards the left of Braddon Bridge.

By now, the vast crowds that line either side of the track turn into a 3D watercolor painting I control, and from now on, all that matters is hitting my lines, staying on track and, most importantly, staying alive.

PRF Racing’s Scott Compsty pushes the GSX-R through tech on the morning of race two.

PRF Racing’s Scott Compsty pushes the GSX-R through tech on the morning of race two.

Getting There

This is my first foray at the Isle of Man, a place near and dear to my family’s heart. I grew up with photos around the house of my father racing his TT Ducati, Yamaha and AJS and while the TT was always something I knew I wanted to do, getting there was another matter entirely.

My “in” came via the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, where I won the final motorcycle event in 2019. A quick visit to the Isle at the end of 2019 confirmed that, yes, I did want to take on this greatest of challenges, but with two-and-a-half years of Covid-induced hiatus, I had plenty of time to talk myself out of doing the race—but not enough time, as it turned out.

My team for the event was PRF Racing run by Paul Rennie out of Skelmersdale in Lancashire, England, an outfit that has been around since 1995 and seen success with team rider and Paul’s brother, Carl Rennie. I figured with the same name as me, albeit as a surname, this was a good omen for a solid TT debut.

After arriving on the island a week before the first night of practice to get my bearings and, more importantly, get into the time zone, Paul and I met face to face on Thursday, May 26. A quick test for the Metzeler Moto USA/PRF Racing Suzuki GSX-R600 followed at the Jurby Airfield the next day—this is the traditional shakedown area for TT competitors to get the bike somewhat set up for the rigors of the 37.73-mile course—and although our quickshifter wasn’t working, nor was the gear-position indicator, I still had optimistic feelings about the race proper.

My engine was a beast. Paul said it was good for 137 horsepower, which, if true, put it 18 horsepower up on my personal GSX-R back in California. It pulled hard even with the ultra-tall TT gearing fitted, and the suspension felt near spot on. As it turns out, I didn’t touch the front once for the full two weeks save for two turns of preload, and the rear shock only got a slightly heavier 1.0 kg spring and a bit less preload. Again, good omens.

Home for two weeks was the PRF Racing pit setup.

Home for two weeks was the PRF Racing pit setup.

Step One: Rookie Laps

Having spent hours on the PlayStation, watched countless YouTube onboards and spending a week doing car laps of the track with rookie liaison officers Richard “Milky” Quale and Johnny Barton, I felt I was in a good position, knowledge-wise, as we walked up to the packed grid to complete my rookie speed-controlled lap on Saturday afternoon.

This is something every new TT rider has to do, from Honda Britain’s Glenn Irwin right down to little ol’ me. This lap is held at the beginning of the first session of practice week, when enthusiasm is at its highest and the cameras are rolling everywhere.

I wasn’t even nervous. A little excited, a bit edgy, but just looking forward to getting this lap out of the way so I could start my TT apprenticeship.

However, my GSX-R refused to play ball.

The Suzuki GSX-R600 had started every time prior, but when the moment came to fire up on Glencrutchery Road—crickets. With cameras pointing and onlookers onlooking, all I could do was sit there as Paul and Scott from PRF began dissembling the bodywork on the grid to find some electronic gremlin hiding between the Suzuki’s frame rails.

The King of The Mountain, Peter Hickman. The lap-record holder was a great help to Rennie, offering lots of insights only a man of his experience would know.

The King of The Mountain, Peter Hickman. The lap-record holder was a great help to Rennie, offering lots of insights only a man of his experience would know.

Johnny Barton waited and waited, but eventually, he and the three rookies in his care had to go, leaving me stranded on the grid and the organizers telling Paul to take the bike and all its bits back to the pits. We were thus informed we would miss out on the whole day of practice, which, for a rookie like me, was devastating news.

The whole experience was topped by a kid on a BMX bike with his buddies who came asking for an autograph in the pits about an hour later.

“Was that your bike that wouldn’t start on the line?”

“Yes, mate, it was.”

“Gee, that’s a bit embarrassing, innit?”

All I could do was laugh. I’d been totally owned by an 11-year-old.

Eventually, Paul traced the problem to a throttle position sensor and the switch block on the left handlebar that held the pit lane speed limiter, and thanks to Milky Quale, I managed to get my rookie lap in at the end of the day and was thus allowed to start Sunday nights’ practice.

Rennie trying frantically to hang onto Richard ‘Milky’ Quale’s exhaust pipe on his belated rookie lap on night one.

Rennie trying frantically to hang onto Richard ‘Milky’ Quale’s exhaust pipe on his belated rookie lap on night one.

This Is F’ing Nuts!

That first lap behind Milky was an experience I will never, ever, forget. Going down the Sulby Straight, pinned in sixth gear while trying like hell to keep Milky and his CBR1000 RR-R SP marshal bike in sight, I remember yelling in my helmet, “this is f’ng nuts!”

And it was nuts.

How on earth was this legal? Not just legal, but actively encouraged. I came over the mountain from Hailwood Heights to Windy Corner totally aware of my own mortality, knowing if I messed up here, it was the last time I would ever do so.

But the fear was balanced by unbridled exhilaration. I’d forgotten about the Suzuki’s electronic problem. The bike was going great. And I was living my oldest dream of riding the TT course.

I came in and immediately gave Milky a hug. If someone had turned my lights out for good right there and then, I’d have died a happy man. The pure, uncut adrenaline, I’d never felt anything like it. It was needle-in-the-arm stuff.

Before I could ask Paul about what he planned to do regarding the Suzuki’s electrical problem, he told me he was going to replace the whole wiring loom and the switch block for Monday night.

And true to his word, the Suzuki was beautiful for what turned out to be my first real night of practice. I went to 109.9 mph average for the second lap—my first flying lap of the track—but the session was cut short when Sam West lost control of his BMW through the Laurel Bank section of the course, his cartwheeling bike splitting its fuel tank and exploding into flames and incinerating part of the hedge.

I was stopped at Parliament Square in Ramsay after two and a half laps, which was almost welcome as my shoulders felt like they’d done six rounds with a heavyweight UFC fighter.

I was told my upper body would take a beating at the TT, much more than in regular racing, but I could hardly believe just how sore the muscles around the front of my shoulders and those on my neck were. I could barely lift my left arm. How was I going to do a full four-lapper?

Sometimes, one can TT themselves too hard.

Sometimes, one can TT themselves too hard.

Getting The Hang Of It

My second night of practice on Tuesday was going brilliantly. Coming in after two laps to get a drink, a visor change and a tank of fuel, I headed out, completed lap three at 113.15 mph and thought a fourth-lap flyer would put me at least into the 114-mph bracket.

However, any thought of bettering my speed was quickly replaced with one of bewilderment as coming over the jump at Rhencullen, I felt a massive knock coming from the front end of the Suzuki. At first, I thought my steering head was loose, then I pushed on my left handlebar and felt the knock again.

I pulled into the driveway of the Bishopscourt section of the track, a daunting, sixth gear thread-the-needle section of the track that for me is way more intimidating than Bray Hill or even Ballagarey.

The marshal came up to me with a concerned look on his face.

“What’s the matter, lad?”

“I think my handlebar is loose, mate.”

“Really? No…”

He came up to the Suzuki, gave the left handlebar a slight tug, and out it popped from the clamp.

I nearly fainted, and the disbelieving look on the few spectator’s faces that were there was all I needed.

Two rookies, one miles away from the other. At least Rennie was gracious enough to have his photo taken with the fastest rookie ever at the Isle of Man in factory Honda rider, Glenn Irwin.

Two rookies, one miles away from the other. At least Rennie was gracious enough to have his photo taken with the fastest rookie ever at the Isle of Man in factory Honda rider, Glenn Irwin.

One of them rushed away to find an Allen key set so I could tighten the bar back up, and I triple checked everything else just so I’d make it home okay. Furious, I cruised back to the pits, shot Paul a gnarly look as I handed him the bike and told him, rather loudly, “the f’ing handlebar fell off!”

Paul told me this was the first time something like a handlebar coming loose happened to his team in its history, but it was still a major knock to my confidence.

Milky Quale was a good help in this moment.

“Things break here that don’t break anywhere else, mate, don’t let it get to you.”

He was right. I couldn’t let that stuff play on my mind, but each time I got on the bike, my sponsor from Metzeler USA, Oscar Solis and I, went over all the fastening bolts just to make sure.

Battle stations. In less than a minute you’ll be going 160 mph between the houses and down Bray Hill.

Battle stations. In less than a minute you’ll be going 160 mph between the houses and down Bray Hill.

The TT Shows Its Teeth

We needed some good luck after the last few days and day four (three for me) started out well. With two laps under my belt, I was lying in 18th overall and feeling quite chuffed with myself, having knocked out a 114.56-mph run on lap two.

Earlier in that run, Mark Purslow and his sky-blue Yamaha YZF-R6 passed me on the Cronk-y-voddy straight, dragging me into the daunting right hander faster than I’d ever gone. His line showed me the right way, the faster way, but he was so quick he was out of sight within five miles.

We crossed each other in the pits as we both refueled and Mark had trouble getting his bike turned around. Thus, I leapfrogged him on the road. Setting off for lap three, I knew he was right behind me, and I put my head down and nailed my now beautifully handling Suzuki as hard as I could to build a gap to Mark.

Coming through Greeber Castle and into Appledean, there in front of me flashed the red flag light. Looking behind me, Mark was nowhere to be seen. I thought he must have pulled off after the Crosby Jump.

I pulled into Ballacraine along with riders Paul Williams and Mark Goodings and was told there was an accident at Ballagarey—the hair-raising near-top-speed right-hander Guy Martin made famous by his fireball crash in 2010 that he miraculously survived.

After a little while, I realized it was Purslow who had gone down. It’s rare for someone to survive a crash at Ballagarey, yet we all held out hope. But the longer we waited, the more apparent it was that this was a very grave accident indeed.

The news filtered through a few hours later that Mark Purslow had lost his life. One of the fast up-and-comers of the TT who had tasted success at the Manx Grand Prix, Mark was living his dream when it all came to an abrupt end. He was 29.

It was my first brush with death at the TT, and, sadly, wouldn’t be the last.

The Barregarrow section of the track is proper gnarly as Rennie totally G’s out the Suzuki with Gary Vines in pursuit.

The Barregarrow section of the track is proper gnarly as Rennie totally G’s out the Suzuki with Gary Vines in pursuit.

Living The TT Dream

Qualifying night five was one of those nights that will stay with me for the rest of my life. Four full laps, including two flyers, with the little Suzuki and I gelling like dance partners. Lap four was pure ecstasy, catching and passing multiple riders from Union Mills to Governor’s Bridge for the first time and pulling away like they were doing to me only yesterday.

With no red flags, no crashes for anyone, I rocked out a 117.07-mph lap to finish 22nd for the night, one place behind my old sparring partner from CVMA, Chris Sarbora. I was utterly beaming. That lap was, categorically, the most fun I’ve ever had on a bike. I started to feel like I belonged, that I could do this. I was capable of becoming a TT rider.

This euphoria, however, was quashed the following night. I rode terribly, got too full of myself, and couldn’t go as fast as I did the night before, when everyone else did. I peaked too early, and the TT Mountain Course slapped me firmly into place.

Then on the final lap, coming into Joey’s on the Mountain, I saw an explosion of haybales. Bits of bike, too smashed to be recognizable, were strewn across the track, and I could vaguely make out the mangled figure of a rider on the side of the road.

Thankfully, I couldn’t see who it was, and with the medics attending, I put it out of my mind and got back on with the job of finishing the lap and the night.

On returning to the pits, my mate Al Fagan from 44 Teeth rushed up to me, concern written across his face.

“Have you seen Boothy?”

Turns out that figure on the ground was my colleague, Mike Booth, from 44teeth.com, the British bike review website and YouTube channel that’s one of my favorites in this industry.

“No, mate, I couldn’t see it was him, all I could see was a rider and bits of bike everywhere.”

Honestly, it didn’t look good, and it wasn’t. Boothy, the man who just two days ago was hugging me and giving me tips and pointers as a fellow journo and TT rider, had suffered very serious leg injuries, his right leg subsequently being amputated below the knee, among other major leg complications. Suffice it to say, it took whatever wind was in my sails firmly out.

Out of Sulby Bridge on the final lap of the second TT. By now, everything was starting to click.

Out of Sulby Bridge on the final lap of the second TT. By now, everything was starting to click.

A Bit Of R&R?

That was it for practice, but I noticed the Suzuki jumped out of gear a couple of times over the course of that final lap. Reporting this back to Paul and the team, they changed the height of the gearshifter and we decided on a preload and gearing change for the Saturday warm-up lap as a bit of a tester for the race. After all, it was the only track time we had left before our race on Monday.

Lining up on Saturday morning, I dumped the clutch and sped through first gear, went for second gear and—nothing. With the revs below 8000 rpm, the Suzuki finally shifted into second, and I went for third and—nothing.

I still don’t know exactly what happened, but the gearbox had suffered a terminal problem. I coasted down Bray Hill and exited stage left—the TT strikes again.

Back at the pit, there was a slight sense of foreboding as yet another technical problem put a stop to a lap. Paul sprang into action, pulling the clutch apart, trying to figure if the problem could be solved without changing the engine. As it turns out, it couldn’t, so it was another long afternoon for him and Scott who not only had to replace the motor but also weld the frame that had cracked at the gearbox mount.

Paul miraculously pulled the motor out within an hour, had the frame welded within the next hour, and the new motor in by the end of the day. A quick dyno run ensued where we noted we were 10 horsepower down on the old motor, but it was a fresh one after all and would probably gain a few more ponies as it loosened up. At least we had a working motorcycle.

I used this time to play spectator, watching the real heroes of the TT do their thing in the Superbike race and to support my mate, Brandon Cretu, in his TT return on the Team Penz Honda CBR1000 RR-R SP2.

Seeing the TT from this angle gave it a new meaning and really bought home just what it means to the island and the people who come to see it. When you’re racing, all that matters is you. But when you’re spectating, the event takes on a new level and you can’t help but fall in love with the place, no matter the hardships it dishes out.

The day after. Rennie sharing a beer with lifetime friends Simon (center) and Rob as the TT comedown begins.

The day after. Rennie sharing a beer with lifetime friends Simon (center) and Rob as the TT comedown begins.

Race Time

With no competition on Sunday, my crew of Simon, Oscar and Cristi did a bit of sightseeing and visited Castletown to, you know, go to a medieval castle. It was a nice reprieve from the racing and showed another, far more ancient side to the isle.

With a good night’s sleep under my belt, I was ready to rock for race one on Monday. Paul and Scott had the bike running great but going into a TT with an untested engine was a little off putting.

Like my rookie lap, I wasn’t even nervous. The start is so frantic that you barely have time to get nervous before your famous shoulder tap, and once I was underway, all I could do was ride as hard and as safely as I could and hope not to make any stupid mistakes.

But by the end of the second lap, I’d been caught by Gary Vines, the rider who started directly behind me. I’d been too cautious on the first lap as I felt the engine and made sure everything was fine before being comfortable enough to really send it, and Gary’s CBR came roaring past coming into Schoolhouse Corner in the town of Ramsay.

Full send at the top of sixth gear through the daunting Molyneux’s right-hander on the final night of practice.

Full send at the top of sixth gear through the daunting Molyneux’s right-hander on the final night of practice.

Here’s where a characteristic of the TT shines through. I felt I was faster than Gary. I was quicker in qualifying, and my bike accelerated quicker than his, but the ultra-high speed nature of the track means it’s damn near impossible to get away thanks to the slipstream.

Gary and I thus played cat and mouse for two and a half laps, which gradually dragged both our average speeds down.

The race had been shortened to three laps and coming into the 27th Milestone, there was once again devastation. Haybales blown out and yellow flags flying furiously, Gary and I slowed to a crawl and rode through onto the Mountain Mile, determined to put what we’d both just seen out of our minds.

Coming into The Nook at the end of the lap, two corners to go, the red flag was flown. To be honest, I was surprised it took that long for the reds to come out given the devastation caused.

Later that afternoon, it was confirmed Davy Morgan, a 20-year veteran of the Isle of Man with 20 TT starts, had lost his life.

Morgan and his famous pink helmet were just in front of Gary and I, just out of sight, when it all went wrong. Davy’s crash cast a large shadow over the race. The paddock was somber, and I have never been so happy to see my little boy, Harvey, on a Facetime call that afternoon, just to bring me back to center. It was a tough end to my first TT, but a reminder of what a knife edge this place can be. I was classified as having finished 44th even though I did not cross the finish line, but it didn’t matter. I just wanted a beer and to go back to the house for a quiet evening.

Flat out through Gorse Lea. This is an intimidating part of the course and the place to spectate if you really want to scare yourself.

Flat out through Gorse Lea. This is an intimidating part of the course and the place to spectate if you really want to scare yourself.

Race Time, Again. Or Is It?

Our second and final race was scheduled for Wednesday, June 8, but the Manx weather had other plans. Gradually dropping rain across the track, we were rescheduled for Thursday and a full four-lap race, so I went to bed early, got the best sleep I’d had in the two weeks and woke ready to give it absolute hell.

The weather looked good, but within an hour of waking up, fog had coated the mountain and we were, once again, informed we wouldn’t be racing that day and were rescheduled again, this time for Friday and a two-lap race.

It was at this point something rather interesting happened. Coming back into the pits at about 11:00 am, I thought I’d go see the team, just to say ‘hi,’ as I was sure they’d be as down as I was that we weren’t racing.

So, you can imagine my surprise when I arrived and my gear was on the grass, the awning taken down, and the bike strapped down in the truck.

As it turns out, my team boss, Paul, had an operation scheduled for Friday back in the UK, and he wasn’t going to miss it, regardless of the fact we still had one more race to do.

I will spare you the details of the language used—there was no way in hell I was not going to take part in that second race—and after a bit of back and forth, I told him I’d run the bike myself. I’d run bikes all over the world before, the bike had a new rear tire and full tank of fuel and as it was a sprint race with no pit stop, there was no reason I couldn’t do it here.

Paul eventually agreed and got the bike out, and gave me the generator, fuel and a small assortment of tools to run the bike. As I watched him pack the PRF complex up, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

But thanks to Oscar Solis and fellow TT rider Shaun Anderson, I had some shelter to put the bike and my gear, and we were good to go. Scott Compsty from PRF also came back to help us get the bike through tech inspection and run it the next day, which was gracious of him given the circumstances.

Photo by iomttpics.com

Photo by iomttpics.com

Race Time. Again. For Real

My second TT came and went in a blur. Being only a two-lap race with no pit stops, it was effectively a sprint race. The wind was incredible across the Mountain, and it was impossible to get sixth gear without a slipstream, which I got on lap two after Spaniard Raul Torras and his Yamaha came by at Ramsay Hairpin.

Following him out of the Creg-ny-Baa right-hander on the last lap and through the glorious, fifth-gear left-hand sweeper of Brandish right behind Torras, I yelled at myself, “Remember this! Remember this!” Perhaps it was a little dramatic, but I will always remember those last five miles or so of the TT course.

I came out of the trees onto Glencrutchery Road and pinned the Suzuki for one final time. Although it was just a sprint race, to see the checkered flag at the Isle of Man TT was the realization of a dream I’ve had since my earliest memories. I’d done it. I’d completed a TT race. No red flags, no accidents, no problems with the bike. It was done.

The relief I felt in that moment was indescribable. Although I missed a bronze replica trophy by just 12 seconds, I improved to 37th and came away happy with that, given the two weeks we’d had.

But the best thing, the thing no one can now ever take away from me, is I can legitimately say I made the oldest dream I’ve ever had come true. I can call myself an Isle of Man TT racer.

Thanks and Cheers

To make something of this magnitude happen, it takes more than just a want to do the TT. This endeavor never would have come to fruition without Paul Phillips at the Isle of Man TT, the man who first gave me the TT green light and who has been at the center of this program since 2019, when I was due to race the TT in 2020.

Rennie with rookie liaison officer, Johnny Barton, a man who was instrumental in helping Rennie learn the 37-mile course.

Rennie with rookie liaison officer, Johnny Barton, a man who was instrumental in helping Rennie learn the 37-mile course.

Thanks must also go Johnny Barton and Milky Quale for their fountains of track knowledge and their advice they gave me while at the track, and my good mate Davo Johnson for putting my name forward as a possible TT racer.

Paul Rennie and Scott Compsty from PRF Racing worked their guts out the whole two weeks and, while it was a shame not to have Paul at the finish, I was incredibly thankful for their time and effort. We had a number of mechanical troubles, but the boys kept charging and gave me a bike I could complete this dream on, so thank you, guys.

Oscar Solis from Pirelli/Metzeler USA was absolutely worth his weight in gold. Not just a sponsor, he helped in so many ways from technical to just being a good ear to listen to my complaining across the two weeks. I thank this guy so much for everything he did. You’re a great mate, Oscar.

Cristi Farrell (left) and Oscar Solis (right), two essential members of Rennie’s TT inner circle.

Cristi Farrell (left) and Oscar Solis (right), two essential members of Rennie’s TT inner circle.

Also, thanks to Cristi Farrell, who came over to be a general help and make things run smoothly in a house full of dudes. Cristi’s help, from getting my helmets to Arai to making coffee for the team, was hugely appreciated, and her calming nature was very much needed at times during the TT.

Thank you also to Heather Watson and Scott Griffin from Pirelli/Metzeler USA. These two have believed in this program from the get-go and I am beyond proud to represent Pirelli in the U.S. but also Metzeler on the biggest stage of them all. The tires were absolutely flawless across the whole two weeks. I never had one concern as to their performance or longevity at the most demanding race track on the planet.

Rookie liaison officer and former TT winner Richard ‘Milky’ Quale—the man has forgotten more about the TT than most will ever know.

Rookie liaison officer and former TT winner Richard ‘Milky’ Quale—the man has forgotten more about the TT than most will ever know.

5.11 Tactical came on board as a personal sponsor this year, and I was so glad to represent an American-made company on the world stage. To have a company as big as 5.11 represented at the TT was a brilliant feeling, and I hope they have seen the exposure motorsport can bring to a company such as this.

Heath Cofran at Alpinestars was the driving force behind creating my beautiful TT race suit. I lost count on the amount of people that came up to me and said they loved the suit, so, Heath, you’ve outdone yourself there, mate. Thank you so much for all your support over the years.

I was equally proud to wear Arai Helmets at the TT. The brand has such a link to the TT and to be part of that story was incredible. The support at the track was second to none, so thank you to Garret, Jeff and Brian for everything you did for me.

Finally, I would like to thank my boss, Sean Finley, for allowing me to chase this dream. Sean’s done so much for my life in America, and I was never prouder than when I put those two Cycle News stickers on the front of the bike the day before practice. CN