Larry Lawrence | June 26, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the June 30, 2010 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

The Cornfield Classic

In 1919 and 1920, the small town of Marion, Indiana, hosted one of the biggest races of the era. The Marion 200-Mile International Road Race brought out all the factory teams, and several teams made “Marion-specials”—racing motorcycles designed specifically to perform well on the five-mile course. The event was heralded with the most grandiose advertisements of the day, and while the Marion 200—or the Cornfield Classic as the press of the day dubbed the race—was one of the biggest races of its era, the event ultimately proved to be short-lived. The reasons for its demise became obvious, as we’ll see, but for a pair of Labor Day weekends, Marion basked in the glory of national attention from its international race.

The battle of the “Big Three” was in full bloom during this period after the end of World War I. Harley-Davidson, Excelsior and Indian were vying for the attention of potential motorcycle buyers, as America was entering one of its most prosperous eras. While people had money to spend, motorcycles had already become somewhat of an enthusiast item other than a cheap form of transportation, which is what they had been considered just a decade before. What once was a low-dollar alternative to expensive automobiles had been turned into what many deemed an impractical form of transportation after Henry Ford ramped up production of the Model T, which made cars affordable to the general public for the first time. Success on the racetrack became even more important for manufacturers to rise above the fray since motorcycles were now more luxury than necessity.

The Marion race was promoted by local Marion businessmen led by a Harley-Davidson distributor named Glenn Scott. Scott’s partners in the venture were bankers, politicians, and the head of the chamber of commerce. The track was a five-mile circuit southwest of town that reportedly cost $75,000 (nearly a million dollars in today’s money). The road-race course was basically a pair of two-mile straightaways connected by shorter half-mile straights—it was a giant rectangle; that’s what they called a road-race course back then. The four turns were 90-degrees and slightly banked. The surface was rolled and oiled gravel. Pits were on the outside of the main straight and a 5000-seat grandstand was built on opposite side of the pits.

The buildup to the race was huge, both in the local media and the motorcycling press. It was originally hoped that the British motorcycle makers would bring their factory teams over (thus, the International designation), but that never happened and the only international entrant in the 1919 race was New Zealand Champion Percy Coleman. The Marion Leader-Tribune newspaper featured a racer each day in its pages in the weeks leading up to the race and the entire front page of the paper the day before the race was devoted to stories of the event.

Admission to the race was one dollar and a reserve seat cost the same. Promoters expected a crowd of 20,000 (about the exact population of Marion at the time) and it’s not clear how they were going to make enough money to cover the cost of building the track, even if they got the 20,000 fans they’d hoped. It is apparent that the town of Marion was contributing in some way financially since the race was seen as a way to promote the town. The few hotels were filled to capacity and Marion residents were asked by city fathers to open their homes to the visitors coming from as far away as Butte, Montana, and Boston, Massachusetts.

Marion was on top of the Trenton Gas Field, the largest natural-gas field ever discovered up to that time. In the 1880s, the field was thought to hold a near endless supply of natural gas and the area boomed with businesses coming in to take advantage of the cheap resource. But, by the early 1910s, the gas field dried up due to waste and overuse, and towns in the area were struggling to keep businesses alive. So, the race was an attempt to advance the cause of Marion commerce.

Harley-Davidson, Indian and Excelsior fielded factory teams with six riders each. All the big names of the day were in the race and all three manufacturers came to the race with machines made to run at maximum, taking advantage of the two-mile long straights. Reports of the day put the top speed of the bikes at 95 mph, a considerable feat considering they were running on oiled gravel.

Harley’s Red Parkhurst won the 200-miler in three hours and six minutes, averaging almost 67 mph in front of a crowd of 12,000 spectators. The race was a coup for Harley-Davidson, which swept the top-three positions, with Ralph Hepburn and Otto Walker taking second and third. Hepburn even broke a chain during the race, put on a new link himself and still finished second. The Motor Company trumpeted the Marion results far and wide via two-page magazine advertisements.

The Motorcycle and Allied Trades Association (predecessor to the AMA) shamelessly exaggerated the race. A statement by the M&ATA’s W.H. Parsons proclaimed, “It was the greatest motorcycle race ever held in the history of the motorcycle trade. We are greatly pleased over the results, and if the people of this community will support it, we would like to make the International Championship Motorcycle Race an annual event in Marion.”

The race did return for one more year. In 1920, the build-up was considerably less than it had been the year before. All the factory teams were back, and Harley-Davidson retained the International Road Race crown with Harley-Davidson Wrecking Crew member Ray Weishaar winning over Indian’s Leonard Buckner. To show you how quickly motorcycle technology was advancing at the time, Weishaar chopped nearly 20 minutes off Parkhurst’s winning time from the year before.

The second year, the newspaper only reported crowds in the thousands, which was a sure sign that the paid attendance was down considerably from the first year. Later articles revealed that officials found it impossible to police the vast five-mile course and locals simply walked through farm fields to watch the race without paying. It was also said that just watching motorcycles zip past on a straight line at 90 mph and then speed off into the distance not to return for another four or five minutes wasn’t a great viewing experience for the fans. Additionally, it became confusing in the three-hour race to keep up with who was running where in the race.

A statement by the M&ATA’s W.H. Parsons proclaimed, “It was the greatest motorcycle race ever held in the history of the motorcycle trade.”

With major losses, the Marion businessmen and politicians gave up on hosting the race after the 1920 Cornfield Classic.

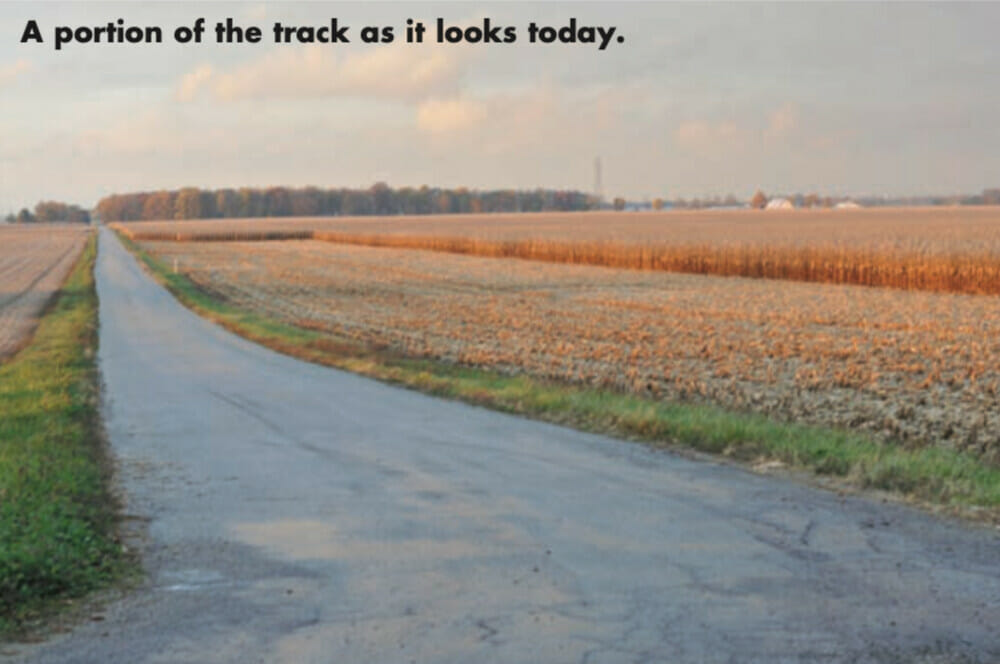

The track is still there southwest of town. The grandstands are long gone and the course itself has been converted to county roads. Today the occasional farmhouse lines the five-mile course. I talked to one resident who lived on the old course, and he’d heard that Marion once hosted a big international event way back when but wasn’t aware that his farm sat on the southwest corner of the old course.

It would be 19 years before Marion would host another National-level race. In 1939, the AMA National TT Championship, predecessor to Peoria, was held in Marion. The race lasted there until 1946, interrupted five years due to World War II. The Marion TT was a humble event compared the former international road race, never drawing more than a few thousand fans.

It didn’t succeed for the long run, but for two years in the post-World War I era, the little gas boom town of Marion, Indiana, hosted the biggest motorcycle road race of its era. CN