Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the November 4, 2009 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

The Trials of Whaley

Marland Whaley was the dominant American Observed Trials rider of the 1970s. In fact, a case could be made that Whaley—who, from 1975 to 1980, won five National Observed Trials Championships—is one of the true elite riders in the history of trials competition.

In 1977 he turned in the perfect season, going undefeated in all eight rounds in which he competed and clinching the title with three rounds remaining. One might think that Whaley’s accomplishments would earn him a place in the Motorcycle Hall of Fame or at the very least the North American Trials Council’s Hall of Fame, but Whaley seems to be the forgotten man of observed trials.

Whaley’s dad was a successful local racer during the 1950s and early ’60s and young Marland grew up going to the events with his dad. Thus, motorcycles were always a part of his life. Finding a place to ride wasn’t an issue.

“I would push my bike a half a block up the street and be on the trails and up into the hills,” Whaley recalls.

Living in the San Diego suburb of Santee, Whaley knew and rode with many of the area’s motocross riders—guys like the “Martys”: Tripes, Smith and Moates. While most of his fellow riders were ripping around the trails at speed, Whaley seemed to be attracted to testing himself on more technical trails, seeing if he could negotiate a hill or a rock that no one had thought about trying before.

Whaley was a big kid for his age (he would eventually grow to 6-foot-2) and was riding full-size motorcycles by the time he was 11. Shortly afterward, he was competing in his first trials event on a Montesa 250, and things progressed quickly for Whaley from there. Backed by Montesa at 13, he won the California State Championship in observed trials when he was just a freshman in high school, beating established national riders like Lane Leavitt.

“I even shocked myself when I won that first California State Championship,” Whaley said. “I think I was ranked third coming into the final event, and the final round was up in Hollister, and my competition didn’t have such a great day and I did. Winning that was so unexpected. I remember we were driving home and that night I couldn’t sleep I was so excited.”

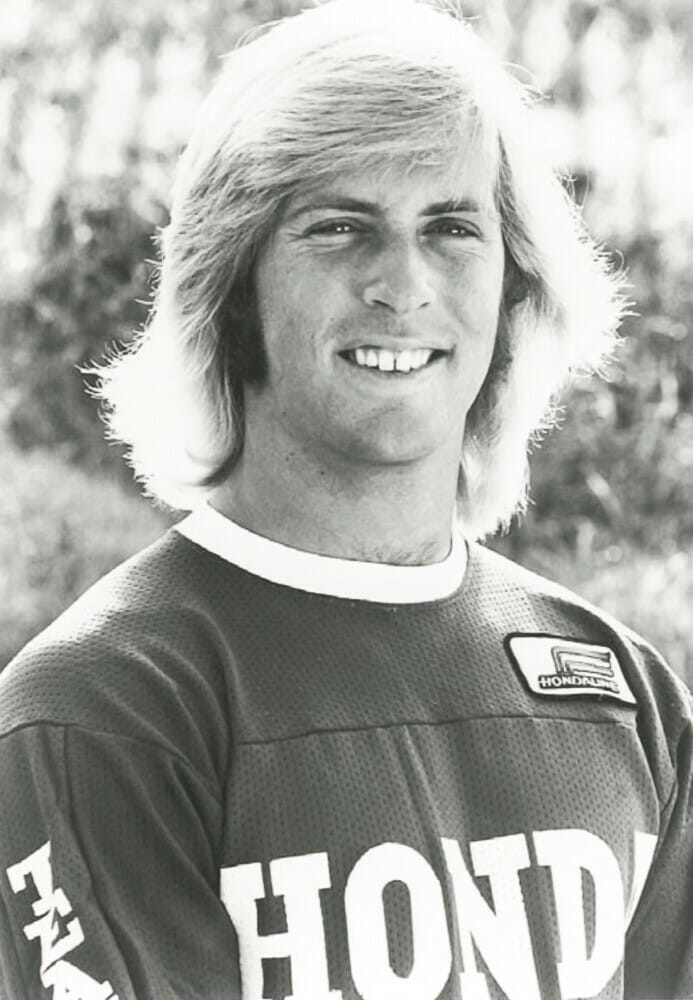

Whaley was fortunate in that the Japanese manufacturers were getting involved in making trials machines just as he was emerging as one of the sport’s up-and-comers. At just 16, Whaley got the dream job when he became a paid factory rider for Honda. The pairing proved fruitful. With the resources of Honda behind him, Whaley dominated observed trials from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s—a Golden era in trials when all four Japanese makers and several European companies were fielding teams in the sport.

Honda got into observed trials trying to make a four-stroke competitive against the dominant two-strokes of the era and Whaley remembers the first factory Honda trials machine was a 305cc long-stroke single.

“It had a lot of titanium parts and only weighed 192 pounds, which was very light for a four-stroke,” Whaley said.

It was a busy time for Whaley. Not only was he competing at events around the world, but Honda also had him testing various engine configurations, including the earliest short-stroke singles that would later come to dominate the sport.

The only hiccup in Whaley’s 1970s domination came in 1978, when he said he had a nightmare year where everything that could go wrong, did go wrong.

“It was so bad on and off the track for me that year,” Whaley recalls. “One night Marty Tripes and I were driving our Porsches like idiots, going down to Mexico to get some tacos, when I spun out, hit a boulder and knocked the motor out the side of the car and rendering it virtually worthless. I ran a saw through my thigh doing a home landscaping project. If I hadn’t been living it, it would have been funny. It was like ‘what else could go wrong?’”

When asked how a trials rider, even a factory one, could afford a Porsche, Whaley explained that his contract was incentive based.

“It wasn’t like my motocross buddies who were making big bucks regardless of where they finished,” he said. “If I won events, I did well, and, fortunately, in 1977, I won everything, so it was a really good year for me.”

Whaley said he’s proud he accomplished what he did during a time when trials was at a high point in America. “With all the factories involved, there were a lot of talented riders,” Whaley says. “There was Lane [Leavitt], Bernie [Schreiber], Joe Gugielmelli, Don Sweet from New York. There were a handful of riders on any given day who could win. There doesn’t seem to be as much interest in the sport these days. It just sort of died.”

Bernie Schreiber went on to fame in the World Championships, but despite his talent, Whaley never experienced the same success at the international level.

“I had some good results in Europe, but when I went from Honda to Montesa, it was never the same,” he said. “With Honda, if I needed a new part or something it was almost immediate. With Montesa, they had what I call the ‘mañana syndrome.’ Everything was going to be done tomorrow.

They were just so laid back that I had a real hard time meshing with them to the point where it became a problem. I wasn’t over there to just hang out. It didn’t work for me.”

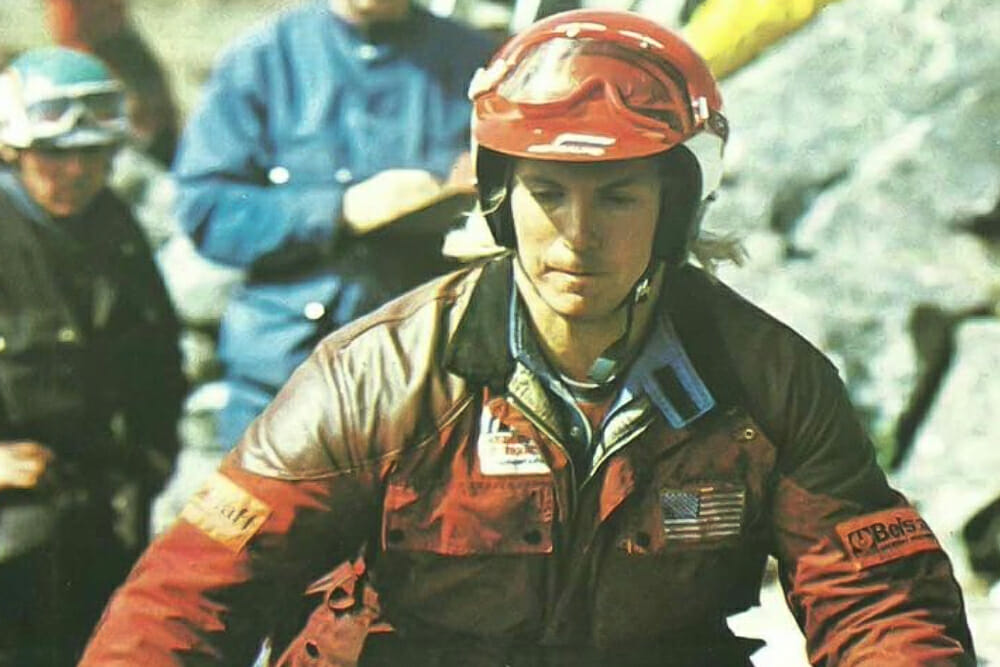

Whaley had his days on every type of trials course, but he was best known for his strength on dry courses with big, steep boulders—like the ones he grew up riding in the San Diego area.

Whaley won his final National Championship in 1980 and after that he raced only sporadically. He rode a couple of events for Beta Motorcycles when that company made its first attempts in trials, but according to Whaley, the Italian bikes at that point were not quite ready for primetime. By the early 1980s, Whaley, who was only 22 at the time, was out of the sport.

“Unless I went full time to Europe, I kind of felt there was nowhere else to go for me,” Whaley said. “I wanted to be remembered as a rider who went out on top and didn’t try to hang on past his prime. You see that happen and so many times riders tend to be remembered as the rider you last saw instead of the rider they were earlier in their career.”

After racing, Whaley became a building contractor and moved to Montana in 1992. There he became a snowboard instructor. His second wife, Dawn, was also into that line of work. Today, Whaley is a grandfather. He keeps his competitive juices flowing by racing bicycles—both road and mountain bikes.

As for being the forgotten man of observed trials, Whaley says that being away from the sport and living up in a remote part of the country probably hasn’t helped his case.

“I have friends who keep me up to date with what’s going on in the trials world, but I’ve sort of separated myself from it. Although when I moved up here, I was surprised to see how many trials bikes were around. I think I found out where all of Yamaha’s old trials bikes have ended up,” he laughs. “Every hunter up here has one. They don’t know what it is or what it was made for, but, doggone, they sure are geared nice and low so they can get around these trails.” CN

Click here to read the Archives Column in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Subscribe to nearly 50 years of Cycle News Archive issues