Larry Lawrence | January 9, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the October 29, 2008 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

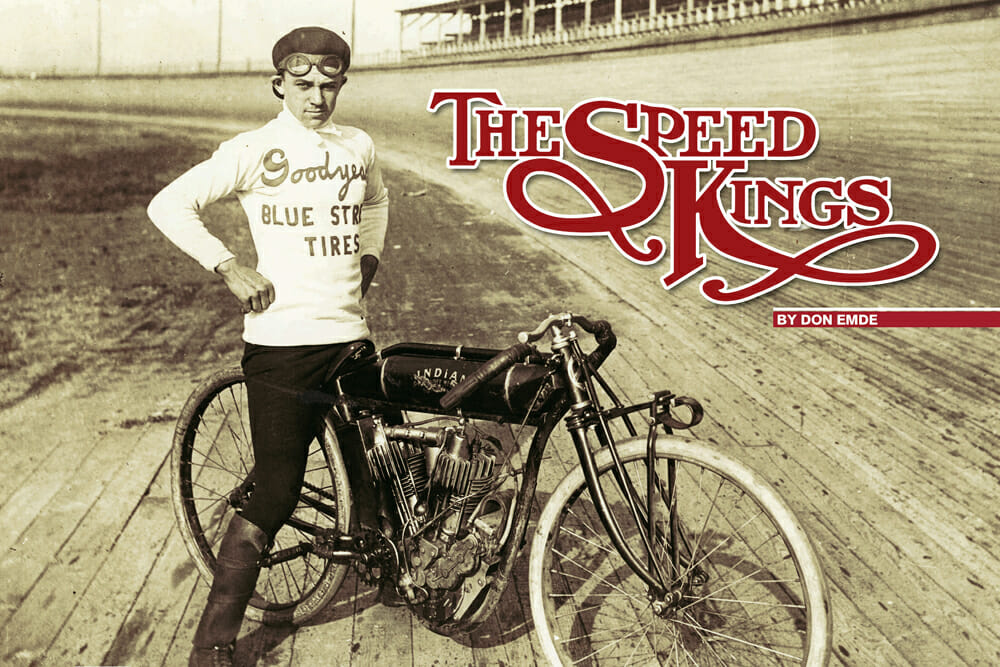

The Champ Who Wrote Speeding Tickets

Fred Ludlow was a top board-track racer of the 1910s who made the transition to dirt-track racing with ease—the culmination of that coming September of 1921 when the Californian won five National Championships at the M&ATA finale on the dirt mile at Syracuse in New York. After his racing career, Ludlow became a motorcycle policeman in Pasadena, California.

Fred Ludlow

Fred Ludlow

Ludlow was born on August 23, 1895, in Los Angeles. He finished two years of high school before being offered a full-time job as a truck driver and that allowed him to save his earnings and purchase his first motorcycle—an Indian. When truck driving proved to be too tame for him, he began racing in the Los Angeles-area motordromes at the age of 16.

The first large wooden track was the Playa del Rey circuit, a one-mile board track west of Los Angeles, and Ludlow became one of the regular riders to compete there. Besides his obvious riding skills, Ludlow also gained a reputation as an excellent mechanic—he was the one turning the wrenches for Charlie “Fearless” Blake during his numerous speed-record runs on the boards during the latter part of 1913.

Indian gave Ludlow support in the form of one of its new eight-valve racing bikes in 1914, and he was a frequent racer on the California circuit, earning victories despite having to go up against established veterans such as Don Johns, Morty Graves and the other top riders of that era.

In 1916 and 1917, Ludlow turned most of his efforts to endurance runs and the diminutive rider earned a slew of perfect scores in those long-distance contests.

Ludlow served in the Signal Corps during World War I, leaving for Europe in April of 1918 and returning from the war in August of 1919. Soon after his discharge, Ludlow was hired by Harley-Davidson’s competition manager Bill Ottoway to race for the Milwaukee-based team. Ludlow’s factory debut came in a November race that year at Ascot Park, but his bike broke a chain, and he was credited with fourth.

The team Harley assembled in 1920, later to be known as the “Wrecking Crew,” was chockful of talent. Ludlow joined Ralph Hepburn, Otto Walker, Red Parkhurst and, later, Jim Davis, Ray Weishaar and Maldwyn Jones, in one of the most powerful factory squads ever put together.

In February of 1920, Harley-Davidson sent some of its top riders, including Ludlow, to Daytona Beach, Florida, to test its new machines and to attempt speed records. Winter storms had left the beach in terrible condition with a rippled surface full of driftwood and other debris. Ludlow tested mostly on Harley ’s single-cylinder machines and made a record one-way run of 103 mph early in the tests. He was also the passenger in a sidecar record run with Red Parkhurst at the controls. To save weight, the sidecar was nothing more than a bare-bones steel shell with no padding. Ludlow donned a thick fur coat in a futile effort to gain some protection, but was still battered around in the sidecar on the rough beach at speeds approaching 90 mph. His entire body was said to be covered with bruises afterwards.

Ludlow raced in most of great races of the day, such as the Dodge City 300. He achieved his greatest success, however, on September 19, 1921, on the famous Syracuse Mile in New York. That day, Ludlow earned a clean sweep of all the national titles up for grabs. Ludlow took five wins in five races on his factory Harley- Davidson, besting most of the top stars of the day, including the likes of Jim Davis, Don Marks and Ralph Hepburn. It was one of the most dominant performances in the history of the sport.

Ludlow ’s popularity was such that Harley-Davidson employed him to travel the country in a sidecar to host racing film shows to various clubs and other organizations interested in racing. Surprisingly, Ludlow’s success at Syracuse in 1921 proved to be his swan song on the racetracks of America. He was summarily fired by Harley-Davidson in 1922 and went to work as a mechanic for C. Will Risdon’s Indian dealership in Los Angeles. And in 1923, he joined the South Pasadena Police Department as a motorcycle officer. A year later, he transferred to a similar post in the Pasadena Police Department.

While he did very little track racing, Ludlow turned his attention to top-speed-record attempts on the various dry lakes in Southern California, and he became known as one of the best in the field of record speed runs. Ludlow topped all riders at the AMA-sanctioned Los Angeles Speed Trials on Muroc Dry Lake in 1936 before an estimated 3000 spectators. Ludlow averaged 128.57 mph on a 1936 Indian Sport Scout to top an impressive field of competitors. Indian proudly advertised Ludlow’s accomplishments in the motorcycle magazines of the day. Muroc was later closed to the public and became part of Edwards Air Force Base, site of the first sound-barrier jet flights and, later, NASA space-shuttle landings.

In the fall of 1938, a group of Indian enthusiasts, headquartered out of Hap Alzina’s Indian dealership in Oakland, California, made an ill-fated attempt on the world motorcycle land-speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. Ludlow, then 43, was selected to ride the totally enclosed streamlined machine christened the “Arrow.”

To warm up at the Salt Flats, Ludlow first rode an Indian Sport Scout and set a new AMA Class C record of 115.226 mph. He then wedged himself into the tight confines of the “Arrow” for the land-speed-record attempt. On only the second run, the rear tire blew out and the torn tube struck Ludlow, though he was able to wrestle the machine to a stop. After extensive repairs, the “Arrow” was ready for a run the next morning. On the first run, Ludlow experienced a wobble at 135 mph. The crew cut off two small stabilizing fins thought to have caused the problem. The next day another attempt was made. This time, at approximately 145 mph, the Arrow went into gyrations so violent that the handlebars were torn from Ludlow’s hands. Alzina ordered further “Arrow ” runs scratched and the “Arrow ” was never run again. It was later restored and was part of the Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum exhibit presented by Progressive Insurance titled “A Century of Indian” that marked the 100th anniversary of Indian’s founding.

Ludlow spent the rest of his working days with the Pasadena Police Department. He was a favorite speaker at various motorcycle gatherings and was an authority on early motorcycle competition. Ludlow died in 1984 at the age of 89. CN

If you want to dig deeper into Fred Ludlow’s story, Don Emde just released a book compiled from Ludlow’s personal scrapbook of photos and handwritten captions. You can learn more here about the book entitled The Speed Kings. The Rise and Fall of Motordrome Racing, By Don Emde.