Larry Lawrence | December 19, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the June 4, 2008 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Gunnar’s Big Prediction

Gunnar Lindstrom was introduced to the podium by Bill France himself at the 1971 Daytona Prize Ceremony, a huge banquet that used to be held at the convention center on Sunday night after the Daytona 200. Lindstrom had just won the very first supercross race held at Daytona, at a time before the term “supercross” had even been invented. Lindstrom came to the podium and boldly predicted that maybe someday the motocross race at Daytona would be bigger than the 200. Gunnar’s big prediction was greeted with laughter—the crowd thought that maybe the young Swede was joking. But he wasn’t. And even though at the time the idea may have been laughable, looking back, Lindstrom’s foresight was amazing. Looking into the full grandstands at the Daytona Supercross (these days), one could plainly see what event is the premier race of Bike Week—at least to race fans.

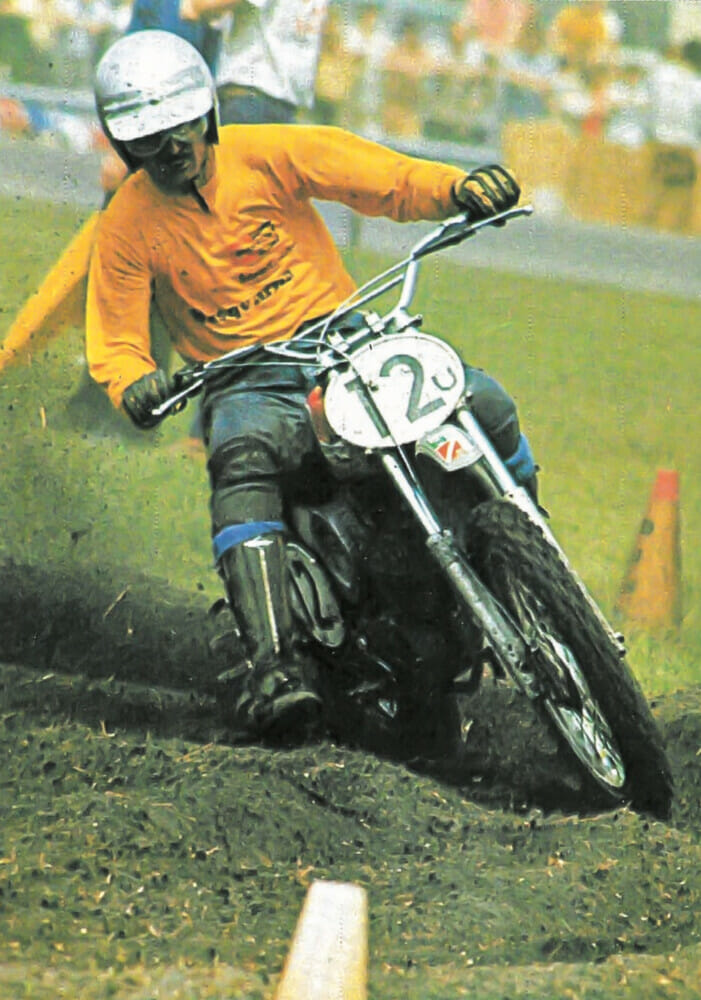

Gunnar Lindstrom won the very first supercross race held at Daytona, at a time before the term “supercross” had even been invented.

Gunnar Lindstrom won the very first supercross race held at Daytona, at a time before the term “supercross” had even been invented.

Lindstrom was born in 1943 in Sweden, where he was raised on a farm. He became interested in motors at a very young age. As a teenager, he bought a basket-case motor and rebuilt it to mount on his bicycle.

“I was as surprised as anyone that it actually ran,” Lindstrom remembers.

Strict Swedish motoring rules prevented riders from taking up motorcycling before the age of 16, but Lindstrom broke those rules and rode all around with older buddies. He grew up not far from the Husqvarna factory, and his childhood ambition was to design motorcycles for the company.

As soon as he turned 16, Lindstrom began racing in all types of motorcycle competition in Sweden, racing on street bikes that he’d modified into off-road machines. His first race was a trials event.

“I knew nothing about trials,” Lindstrom admitted, “but I was just happy to paint a number on my motorcycle and say I was a racer.”

At first, Lindstrom studied agriculture in college, with the idea of staying in the family business. However, he soon decided to follow his dream and switched to engineering. During college, he continued to race enduros and motocross, with good success.

After graduating from college, Lindstrom fulfilled his lifelong ambition and went to work for Husqvarna. His first job for the company was as a test rider. His job was to ride 200 kilometers per day—year-round—and during the long Swedish winter months, his bike was fitted with ski outriggers. He then moved into engineering, developing chassis and suspension.

Lindstrom’s racing career continued, and he became one of the top Swedish motocross riders and also competed in select Grand Prix motocross races throughout Europe. At the end of 1967, Lindstrom’s life took an unexpected turn when he was invited to race in a motocross series held during the off-season in Australia and New Zealand. While there, he met American off-road great J.N. Roberts. Lindstrom won several races in the Australian and New Zealand series, and Roberts asked him to come to America to team with him in the Mint 400. The duo won the Mint and earned $4100.

“We got paid in cash,” Lindstrom remembers. “We laid out the money across the bed of the hotel we were staying in and took a photograph. For a farm boy from Sweden, I thought I was rich.”

By 1969, Husqvarna sales were beginning to take off in America, and the company asked Lindstrom to work out of its American headquarters in New Jersey. While there, Lindstrom said he basically lived out of a motorhome as Husqvarna’s American engineering head.

During the late 1960s, motocross really began to take off in America, and Lindstrom was one of the top riders in the early Trans-AMA and Inter-AMA series. He finished sixth in 1970, the first year of the Trans-AMA Series. In 1971, Lindstrom was third overall in the 250cc Inter-AMA Series and was classified first American finisher in three of the six events, since he was by then living permanently in the country.

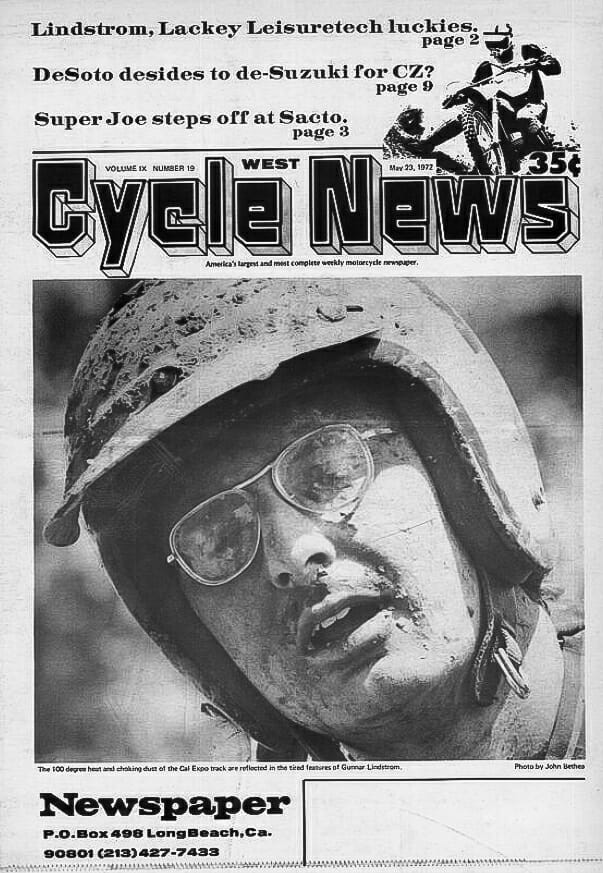

Lindstrom was pictured on the cover of Cycle News in 1972 after winning the Hangtown National MX in 100-plus-degree temperatures.

Lindstrom was pictured on the cover of Cycle News in 1972 after winning the Hangtown National MX in 100-plus-degree temperatures.

The first independent AMA National Motocross Series was launched in 1972, and Lindstrom, on a Husqvarna, won the Hangtown 250cc National held near Sacramento, California, in May of that year. He went on to finish third in the 250cc National Championship, behind Gary Jones and Jim Weinert. Lindstrom retired from full-time racing after 1972, but he continued to race selected events through the mid-1970s. In addition to motocross, Lindstrom also competed in off-road events such as International Six Days qualifiers and long-distance off-road events like the Baja 500.

Differences regarding design concepts with one of his superiors in Sweden led to Lindstrom’s departure from his beloved Husqvarna in 1974. After leaving Husky, Lindstrom became editor of Dirt Bike magazine. Under his guidance, more emphasis was placed on testing motorcycles, and Lindstrom’s engineering background helped introduce a new level of professionalism to the magazine.

While he enjoyed his stint at Dirt Bike, in the back of his mind, Lindstrom thought of the magazine job as a stepping-stone to a better-paying position.

“I thought I might become someone who translated Swedish to English and vice versa for a major company,” Lindstrom said. “I knew the magazine work would provide me with a resume that proved I could write in English.”

In 1978, Honda brought in Lindstrom to manage its motocross racing program. A few years later, he moved into the automotive division. He eventually became senior manager of American Honda’s Alternative Fuel Vehicle programs and spearheaded Honda’s Natural Gas Vehicle program. Lindstrom retired from Honda after 30 years. His son Lars was a Honda motocross test rider and then became a race technician for riders such as Jeremy McGrath, Kevin Windham and Chad Reed. He was named the new Honda HRC Team Manager, succeeding Erik Kehoe, after the 2021 season.

“Everyone back then thought I was just one of those arrogant Swedish riders,” Lindstrom said of his banquet speech at Daytona in 1971. “They thought my prediction was incredibly funny, but stupid. You look back and now it doesn’t look like it was too bad.” CN