Shan Moore | December 15, 2021

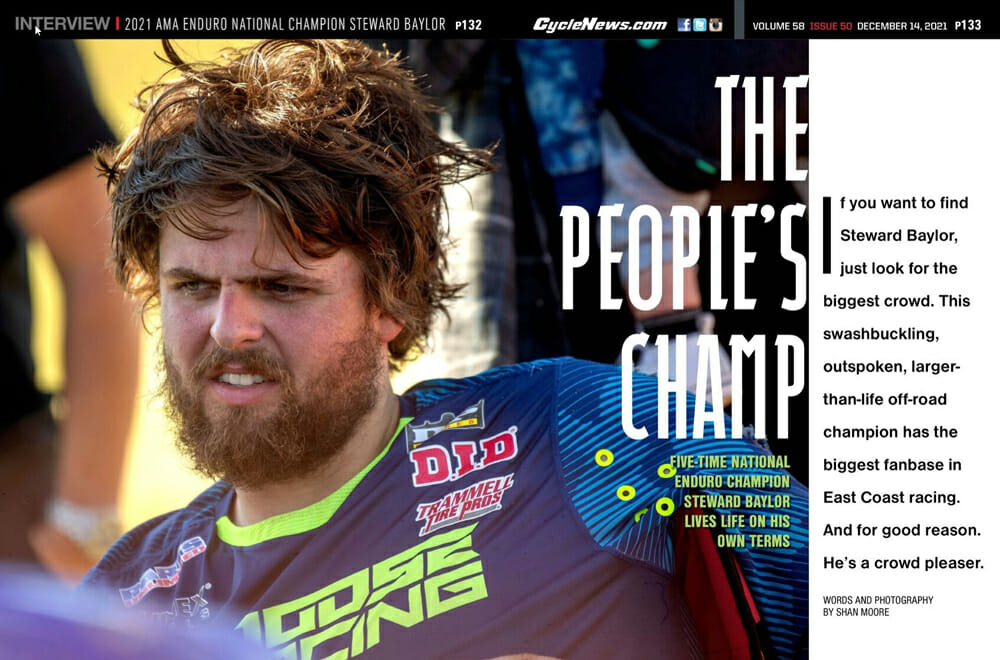

Five-time National Enduro Champion Steward Baylor lives life on his own terms.

Words and Photography by Shan Moore

If you want to find Steward Baylor, just look for the biggest crowd. This swashbuckling, outspoken, larger-than-life off-road champion has the biggest fanbase in East Coast racing. And for good reason. He’s a crowd pleaser.

Every series needs a rogue figure and Baylor is happy to play the part, although he’ll give the shirt off his back to help a fan or a fellow racer in need. One of his most recent crowd-pleasing antics was flipping his bike across the finish line after a win at the Burr Oak GNCC.

“I think the biggest thing that attracts people to me and my racing career has been my personality,” says Baylor. “I think our sport is 100 percent an outdoor lifestyle—go out to the lake on the weekends, have a few beers with your buddies, go deer hunting, I’m going to have some fun. I’m not going to change my normal lifestyle just for racing. The reason I got involved with racing from the start was because I enjoyed it. I feel the reason I have the fan base I do is because most of these guys that are crowding these parking lots, most of these guys that are buying dirt bikes, they started racing because it was fun. It was something they enjoyed doing.”

When he’s on, which is most of the time, there is no one faster in the woods than Steward Baylor right now.

When he’s on, which is most of the time, there is no one faster in the woods than Steward Baylor right now.

In 2021, riding for Randy Hawkins’ AmPro Yamaha outfit, Baylor won his fifth AMA National Enduro title. It was Yamaha’s first National Enduro title since Charlie Mullins in 2010. In addition, Baylor came oh-so-close to adding his first GNCC title in 2021. After missing the opening round of the series due to an injury, he reeled off seven wins in the next nine races to take the lead in the point standings with two rounds remaining, only to drown out his bike at the muddy finale in Indiana. Still, second overall was an amazing feat considering he spotted the field an entire race.

Although Baylor’s style and personality may very well be the reason fans are drawn to him, that flair has had a tendency cause trouble with team managers and owners in the past. For Hawkins, it was a matter of timing.

Baylor (purposefully) looping his motorcycle across the finish line—in first place, of course—has morphed into an expected tradition at GNCC races. He took second in the GNCC title.

Baylor (purposefully) looping his motorcycle across the finish line—in first place, of course—has morphed into an expected tradition at GNCC races. He took second in the GNCC title.

“Maybe if this would have happened three, four, five years ago it might not have worked as well as a program,” said Hawkins. “I do believe when Stew came to our program, the timing was right. He has matured, and I do think there is a bit of mutual respect. I never had a problem with Stew. I watched him grow up as a kid, and as he got older, we didn’t always see eye to eye. But I do believe I have a little bit of an edge on all the other managers of the past. An ace in my pocket, in a sense, is one of his lifelong best friends is Corey MacDonald [Baylor’s current tuner]. Corey has worked for me since he was about 12 years old. If I didn’t have this whole thing put together with Corey, it probably would have been a little bit different. With his relationship and respect from me over time, and lifelong best friends with Corey McDonald, I think it has worked out. Now he’s Stew Baylor. I never want him to lose his personality because that’s what fans love. So, I’ll never ask him to lose that. But I will say from a management standpoint, there’s things that I do expect from him, and he knows it.”

Hawkins started slow, signing Baylor to a series of four one-race deals at the end of the 2020 season to make sure things were going to work out. Baylor won three of the last four races.

Baylor clinched the 2021 National Enduro number-one plate at the final round.

Baylor clinched the 2021 National Enduro number-one plate at the final round.

“Stew’s Sherco deal was kind of going out and I think at times he had been riding a Kawasaki and other bikes, I don’t even know,” says Hawkins. “He reached out to Corey because he was kind of getting to the bottom of his bucket. He said, ‘I need a ride. Do you think Randy would hire me?’ Corey told him, ‘Absolutely not.’ Corey to me two weeks later and he said, ‘Listen, Stew just talked to me. He’s one of my best friends. What do you think?’ I said, ‘Let me talk to him. Let’s see what he’s on.’ At that point, I had a conversation with Stew, and I said, ‘We’ll make this happen. I want you to know, this is a one-race deal.’ He said, ‘That’s all I ask for is a chance.’ Pretty much at that point, it kind of went from there. It was kind of comical when Corey said, ‘Absolutely not.’”

“I never want him to lose his personality because that’s what fans love. So, I’ll never ask him to lose that, but I will say from a management standpoint, there’s things that I do expect from him, and he knows it.” —RANDY HAWKINS

Even with MacDonald’s supervision, Baylor still walks a thin line on the podium, sometimes with a beer can in hand. It’s always a show when he’s up there, you never know what to expect.

“Honesty is something that most racers—it’s not that they don’t have it, it’s that they can’t have it,” says Baylor. “Some of the other teams, manufacturers, and people involved don’t want, honestly. A lot of times they would prefer us lie about what we see and what we feel. I’m not the type of person that’s going to roll over and say, ‘That’s exactly what I saw,’ when somebody tells me what I saw. I’m going to tell exactly what I thought, what I felt.”

Baylor has an exceptionally strong fanbase in both enduro and GNCC.

Baylor has an exceptionally strong fanbase in both enduro and GNCC.

Though it certainly doesn’t affect his racing, Baylor sometimes gets a knock for not looking the part.

“From the time I was 10 or 12, I trained,” says Baylor. “Obviously, I’m the fat kid that looks like he doesn’t train, but I can promise that anybody that’s worked with me understands that I can do anything that the other guys do,” says Baylor. “Physically I do everything they do. I’m just built to be a football player, not a dirt bike racer. I think the big thing with some of the other teams was image. I didn’t fit the mold. I didn’t look like a dirt-bike racer. At 220 pounds, I still don’t look like a dirt-bike racer, but I can promise, my results don’t lie.

“I think early in my career some of the reason the teams and I were butting heads was they thought I wasn’t in shape. They thought I was not doing everything that I needed to do. When teams started getting involved and telling me what I needed to do, it always seemed to have an adverse effect. So, I felt like the biggest thing for me when I went with teams that gave me more control over my situation, I found that I actually enjoyed racing again. That was huge.

“Obviously, I’m the fat kid that looks like he doesn’t train, but I can promise that anybody that’s worked with me understands that I can do anything that the other guys do.” —BAYLOR

I hear the rumors. I see the crap people talk. Yeah, I still drink beer. The guys that I’m competing with go eight months without drinking a beer. So, I get it. But my method is go out, have fun, enjoy your life, enjoy racing. At the end of the day, life goes on and racing doesn’t. With the AmPro Yamaha [team], I’ve actually had freedom. I do push it obviously a lot further than most teams are comfortable with, but we’re slowly working at it and showing that personality can sell bikes just as fast as winning races.”

Regardless of what anyone thinks of Baylor, there’s no denying that he one of the fastest woods riders in the world, especially in really tight woods. Years of practice with his younger brother Grant have molded the two riders into a nearly unstoppable duo on the enduro circuit and each have benefited from pushing the other in practice.

Baylor pretty much marches to his own beat, which he attributes to a large part of his racing success.

Baylor pretty much marches to his own beat, which he attributes to a large part of his racing success.

“Grant and I are polar opposites,” says Baylor. “Grant is very quiet. He’s a homebody. We both have very different styles of riding, ways of life, basically the whole line. I feel like although we did the same things day in and day out, we took completely different paths on how we got there, but we both made it to the top.

“In the tight woods, this year I’ve been very, very reserved at the enduros because I’ve had a little bit of a cushion, and I’ve been kind of more or less managing. But, when it comes down to it, if I really want to use my speed, I feel like aside from Grant and [Josh] Toth on the right day—I don’t think that overall there’s another guy that can go as fast all day long on any different terrain, not just rocks, not just roots, not just tight trees, not just fast trail, sand, etc. I feel like at this point in my career, if or when I want to, I can go faster than any other rider in any terrain, overall. There are days where somebody could be faster, but we’ve worked with such a diverse riding group, had multiple instructors.”

Baylor also thinks living in South Carolina has had something to do with his speed.

“I think the area that we lived in growing up played a huge role into that, as well. In South Carolina, when it rains, we just drive an hour to sand. If we want to ride rocks, we’re an hour from the mountains. Where we live, we have black dirt, red clay, even some rocks. I’ve got some pretty gnarly rocks here. We had so much opportunity. When we rode day in and day out, it was something similar to almost any racecourse. I feel like a lot of our speed came from our early training and a lot of our consistency and different terrains and being able to go just as fast across the board. It’s just the area where we grew up and where we were able to ride.”

There’s not much that’s going to keep him down, either. Baylor, whose mantra is, “If I can still walk and I can still breathe I’m going to race,” has ridden though injuries most of his life, injuries that would keep most anyone else on the couch.

“I think a lot of my injuries come from just being a bigger dude,” says Baylor. “When I hit the deck, something’s got to give. I don’t feel like I’m an out-of-control rider, like I don’t take too many risks. In the earlier parts of my career, I definitely did. A lot of my current injuries that I’m dealing with are old injuries. My hands, my shoulders, my knees—all the stuff I did when I was 15, 16, just kind of young and dumb with my riding, they still catch up with me. But you learn a lot about yourself when you’re pushed into a position that you’ve got to make a decision. At an early age, going back to nine years old, winning my first GNCC Championship, I broke my foot. I knew I could still ride my dirt bike and I could still win this thing. So, we cut the cast off on the way. I told myself I may never get another national championship. I may never get a shot at this again. So, I’m going to do everything I can. That was kind of the first time I had ridden injured, and I was nine years old. I knew at nine years old that was what I wanted to do. Then, in 2012, I broke my wrist and ended up having five surgeries on that. It was for my first national enduro championship. I lined up with the same mentality. Dad said, ‘If you want to race, you’ve got to give it 100 percent. I’ll make sure your bike finishes. If your bike finishes, you’d better be ready to win.’ I’ve kind of stuck with that ever since.”

He can finish second or third but judging by the crowd you’d think Baylor had won. Like him or not, Baylor is good for off-road racing.

He can finish second or third but judging by the crowd you’d think Baylor had won. Like him or not, Baylor is good for off-road racing.

One of Baylor’s most amazing wins in 2021 was not while riding through injury, but when he came from behind to win the Mason-Dixon GNCC when he rode the final lap-and-a-half with no rear brake.

“I told myself I may never get another national championship. I may never get a shot at this again. So, I’m going to do everything I can.” —BAYLOR

“That day I was up front, but I wasn’t leading the race,” said Baylor. “I was a little bit behind, and Ben [Kelley] was starting to pull away. I finally got up close to him and I just put my head down. I think I cut maybe 20 to 30 seconds to catch up to him. At that point, I was still maybe 30 points down in the championship chase and I knew I had to dig deep. Then I caught up to him with two to go, and I ripped my rear brake pedal off. At that point it was like, okay, I’m done. What am I going to do? He started gapping me out, gapping me out another 15, 20 seconds. Everything that I had just cut, I lost again. I got riding and I got in a comfortable zone, and I started chipping away. I came around a left-hander and I could see him at the end of the straightaway. So, I gained 15 seconds in a matter of a mile and a half. From the time I was a kid, one of Jason’s [Raines] big drills was a no rear-brake drill. Come in here and carry speed and keep that suspension freed up and not use the rear brake. So, I spent hours on the bike every week doing simple things like that. Never has it paid off aside from helping me carry some different corner speed, but on that day, it paid off. It’s just one of those headstrong things, but luckily something that we worked on.”CN