Cycle News Staff | September 5, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the November 2, 2005 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Wayback Wake-Up Call:

By Scott Rousseau

Even though America was a latecomer to the sport of motocross, it only took a little more than a decade before American riders dominated the entire scene. In 1967, American riders couldn’t even run with the Europeans. By 1982, America was celebrating the 500cc World Motocross Championship of Brad Lackey and the 250cc World Motocross Championship of Danny LaPorte. And Supercross belonged to America from day one. First seeing the light of day (or should that be the stadium lights of night?) in 1972 at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the brainchild of promoter Mike Goodwin was already on the upswing by the time the third Superbowl of Motocross rolled around on June 22, 1974. The 1972 race had been witnessed by 35,000 fans, and the 1973 race had been witnessed by 38,808 fans. For the 1974 Superbowl, more than 47,000 fans came to watch the race.

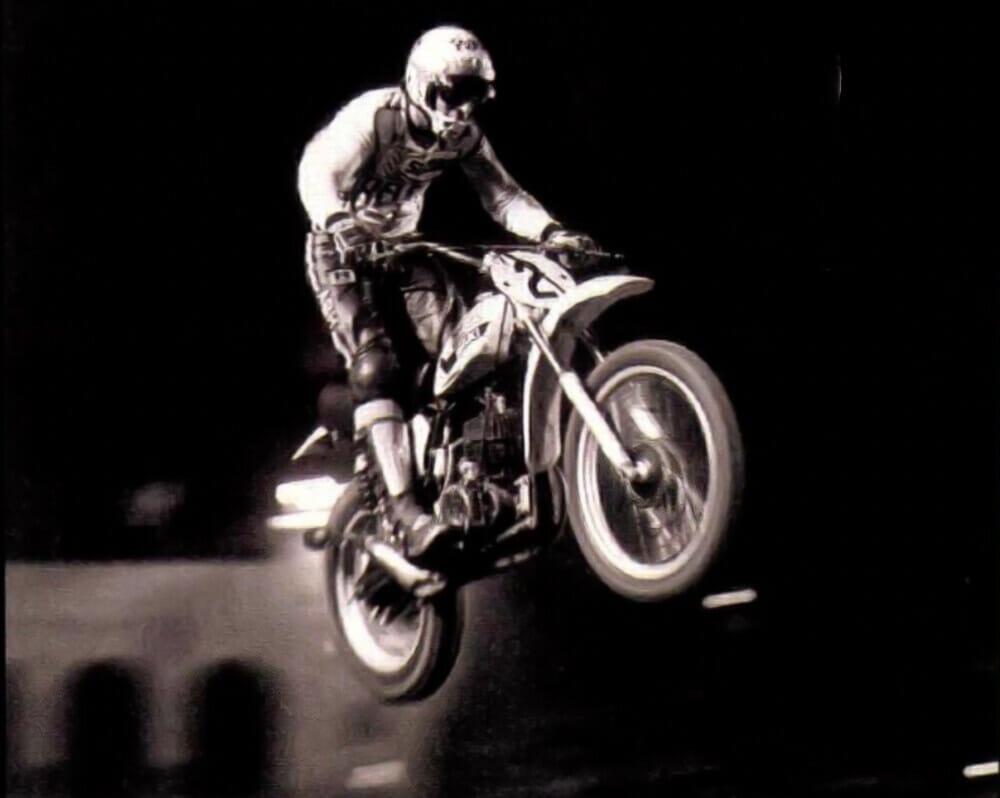

Roger DeCoster was one of the pioneers of Supercross. The multi-time World Championship was lured by the promoter to ride the Superbowl of Motocross at the L.A. Coliseum in 1974. He got paid more in start money than what the actual purse was paying.

Roger DeCoster was one of the pioneers of Supercross. The multi-time World Championship was lured by the promoter to ride the Superbowl of Motocross at the L.A. Coliseum in 1974. He got paid more in start money than what the actual purse was paying.

Despite the presence of top European motocross talent, American boy wonder Marty Tripes had walked away with the first two Superbowl of Motocross titles in convincing fashion, claiming the first win aboard a factory Yamaha and the second aboard a factory Honda. Tripes had ultimately put together consistent-enough motos to swipe the Superbowl crown away from Husqvarna’s Swedish aces Torlief Hansen and Arne Kring in ’72, and he won the first moto and runner-upped in the other two to stand atop the podium in ’73, with fellow American Jim Pomeroy finishing second, while CZ-mounted Czech star Atonin Babarovsky upheld a small measure of European pride by finishing third. The Cycle News reporter writing about the event closed out the ’73 coverage by stating: “Marty Tripes proved that his last Coliseum victory wasn’t a fluke. The Europeans proved that not very many of them bother to come, and that they don’t win anyway.” A bold statement, to be sure, but it did appear as though the mighty Europeans just couldn’t seem to get the hang of racing on tight courses with artificial whoops and jumps under the glare of stadium lighting. Come 1974, however, that would change drastically.

Having switched to Husqvarna, Tripes returned to try and give the European brand its first win in 250cc Supercross against the usual American stars, such as reigning AMA 250cc National Motocross Champion Gary jones, future titlist Tony DiStefano, future AMA Supercross Champion Jimmy Weinert, the Pomeroy brothers, Rich Thorwaldson and Billy Grossi, just to name a few. Making the competition far more intense, however, was a contingent of killer Euros, led by reigning World 500cc Motocross Champion Roger DeCoster and 250cc World Championship contender Jaroslav Falta. Other Euros included Montesa’s Raymond Boven and Peter Lamppu, Suzuki’s Gerritt Wolsink, Kawasaki’s Jan-Eric Sallqvist, CZ’s Zdenek Velky and Husqvarna’s Gunnar Nilsson, making for the toughest field in the young history of the Superbowl of Motocross.

All eyes were on DeCoster, whose exploits in Europe were chronicled well enough in Cycle News and whose Inter-Am visits to America had been frequent enough to gain him “favorite European” status among America’s growing motocross fan base. Promoter Mike Goodwin damn well made sure that DeCoster was part of the ’74 Superbowl.

“Goodwin had contacted me about coming over because I guess they [Americans] knew me from the Trans-AMA races, and he was just trying to build up his program,” DeCoster said.”I guess I was a big draw.”

Indeed, DeCoster had already scored karma points earlier in the year when he won the 500cc class at the Daytona Supercross, but he admits that, unlike the Coliseum, Daytona wasn’t really a Supercross in the truest sense of the word.

“Daytona was outside, like it still is today, so it was not an enclosed stadium,” DeCoster says. “The Coliseum was an enclosed stadium. It was my first time there, and it was big because there was a lot of history with the stadium; they had held the Olympics there and so on.”

DeCoster wasn’t really quite sure what to make of it: “On the one hand it was impressive because of the location—the fact that they let us race inside a stadium—but, on the other hand, I was thinking, ‘All these handmade jumps, this is kind of silly.’”

But that night, DeCoster and Falta proved that it didn’t matter where the dirt was or how it got there. When it came time to step up, both proved that they were world-class. Falta won the first two of the three motos and finished third in the final moto to become the first European ever to win a 250cc Supercross event. At the time, he was the only rider ever to win a 250cc Supercross main event aboard a European brand, CZ. DeCoster went 2-3-1 for second overall, with Tripes upholding a small measure of American pride by going 6-2-3 for third overall. In truth, DeCoster admits that he remembers very little about the actual racing.

DeCoster leads eventual Superbowl winner Jaroslav Falta in 1974.

DeCoster leads eventual Superbowl winner Jaroslav Falta in 1974.

“One thing was that my left grip came completely off the handlebar,” DeCoster says. “I didn’t have my regular mechanic when I came over for the race. It was in between the European schedule, and it was just a quick trip over here. I remember that the grip came completely loose. The other thing that I remember, which is more fun to remember, is that Goodwin was a big businessman, and I was able to get start money from him. That’s a good memory. In America they were not used to doing that, and Goodwin was a tough guy to deal with, but he did pay me $5000 start money for the event. I don’t remember what the purse was, but it was definitely less than the money that I got. I also remember being disappointed that I didn’t win the race.”

Even so, DeCoster is quick to credit Falta.

“Falta was a very good rider,” DeCoster says. “I didn’t have much interaction with him because I was in the 500cc class and he was in the 250cc class, but we would talk. I saw him at the international events, like the Motocross des Nations, and with him being a Czech and me having a special connection with the Czechs, because I went there a lot when I rode for CZ at the beginning and came to the U.S. with CZ and all that, I knew a few words, and we would talk. He was a really nice guy, kind of quiet, but nice.”

More than that, DeCoster, who went on to earn several World Championship and AMA National titles as a rider and then as a team manager, credits Goodwin’s vision of Supercross.

“I could feel from the early days that there was potential there, and I was very impressed with how gutsy Goodwin was to go into a stadium like that and build a track,” DeCoster says. “You could never have gotten away with that in Europe. If you had gone to a football stadium and said that you were going to put 200 truckloads of dirt in there, there’s no way that they would have let you do it. In America, motocross and Supercross are sports that fit Americans, so I thought that the potential was there for the spectators, but I never thought that we’d ever see 25 18-wheelers in the paddock.”

One thing DeCoster doesn’t do is wish that he had been more a part of Supercross during his heyday as a rider. Being there at the beginning—if only briefly—is good enough for him.

“I’m okay with it [my career],” DeCoster says. “There are things that are better today and things that are worse than they were in my racing days. Back then, it was more of an adventure traveling from country to country, but now the world is more similar. Even when you go to Japan, there are McDonald’s everywhere, which makes it less exciting. Back then it was more interesting in many ways. You just have to take it as it comes. Ricky [Carmichael] is making all kinds of money today, but maybe in 10 or 15 years it will be different again.” CN