Larry Lawrence | August 8, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the June 18, 2008 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Freddie And The NR

Honda gave it its best shot. The company gave itself two years to dethrone the mighty MV Augusta and Giacomo Agostini in the coveted 500cc Grand Prix World Championship and came agonizingly close to doing it.

One of the few highlights in the short life of the Honda NR500 was winning a heat race at Laguna Seca in 1981 in the talented hands of a young Freddie Spencer.

One of the few highlights in the short life of the Honda NR500 was winning a heat race at Laguna Seca in 1981 in the talented hands of a young Freddie Spencer.

1967, with Mike Hailwood coming within a whisker of dethroning Agostini on the MV for the 500cc title. They tied in points and had the same number of wins, but Hailwood and Honda lost the title in a second tie breaker—second-place finishes. When the FIM announced new regulations that limited GP machines to four cylinders, Honda, which had famously produced exotic, high-revving six-cylinder four-stroke GP machines earlier in the decade, decided to exit stage left.

MV kept the four-stoke alive in Grand Prix racing for the next few seasons, but by the early part of the 1970s, the Japanese two-strokes were coming on strong. Jack Findlay rode the first two-stroke (a surprisingly close-to-street-trim Suzuki) to a 500cc Grand Prix victory in Ireland in 1971, and Agostini defected to Yamaha and, in 1975, became the first two-stroke rider to win the World Championship. MV put up a good fight, but the tide had turned. The wailing smokers had taken over.

When Honda left Grand Prix racing after 1967, it turned its attention to production-based racing with endurance machines based on its revolutionary CB750 street bike. Yet deep inside the company, a group of engineers, headed by legendary designer Shoichiro Irimajiri, were quietly plotting a GP return with a four-stroke motorcycle.

Honda wanted to return to racing in a big way, and in 1977 it announced that it would return to Grand Prix competition—not with a conventional two-stroke racer, but with a revolutionary oval-piston, four-stroke machine that would showcase Honda’s enormous engineering and R&D capability.

Honda’s insistence on taking a chance that it could advance four-stroke technology far enough to contend with the inherently superior two-stroke design was a case of sticking with the horse that got them to the rodeo. After all, Honda had made its reputation and fortune on revolutionary street bikes such as the groundbreaking CB750. Unlike the other three Japanese manufacturers, Honda’s road lineup consisted primarily of four-stroke-powered bikes. Why should it turn away from its bread and butter? In addition, if the NR were successful, it would prove Honda’s utter engineering domination.

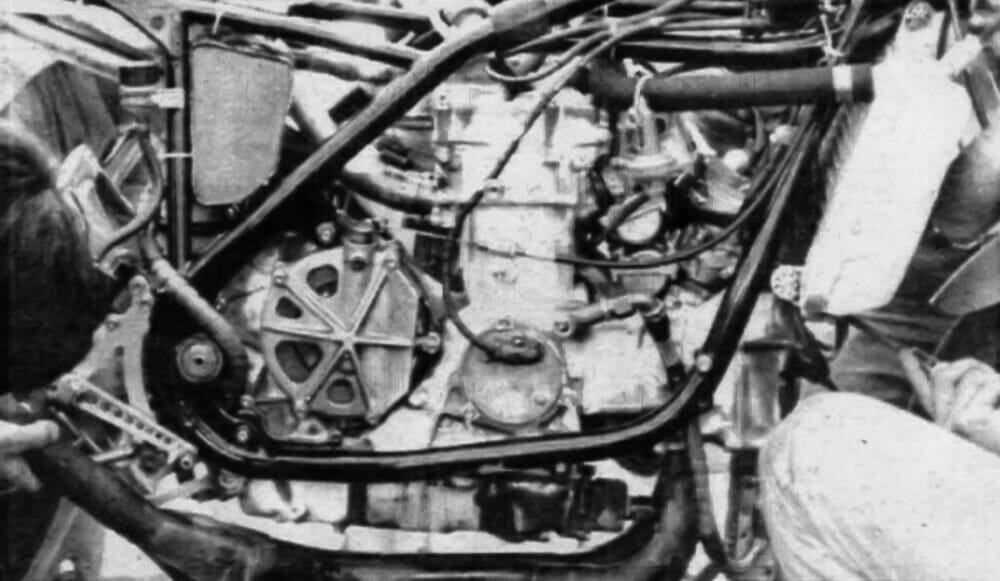

The NR500 was too complicated for its own good. How would you like to work on this on race day?

The NR500 was too complicated for its own good. How would you like to work on this on race day?

Honda campaigned the NR with disastrous results in 1979 and 1980. In its debut at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in August of 1979, neither bike qualified. NR riders Mick Grant and Takazumi Katayama had to be given promoter entries into the race—and neither finished. The NR had twice gone back to Japan for major revamping but was very publicly being humiliated at nearly every outing. Instead of “New Racer,” the motor racing press had dubbed the Honda NR the “Nearly Ready.”

In the United States, Honda had hired a promising up-and-coming racer from Louisiana named Freddie Spencer to race Superbikes. Spencer’s talent was undeniable. He could ride and win on anything, and when his bikes stayed together under him, he won more often than not.

In July of 1981, Honda decided to give Spencer a shot at racing the third-generation NR. The venue would be the AMA National at Laguna Seca. The race, under skilled promotion by Gavin Trippe and Bruce Cox, was supplanting Daytona as the road race in America. With no GP here at the time, Laguna marked the opportunity to see America’s stars who were competing on the GP circuit.

“Honda wanted the American fans to see the NR before they put it in a museum,” Spencer recalled. “Even though the bike was not producing results, it was an engineering marvel, and was so far ahead of its time in technology, it helped give Honda the background it needed to later produce its V-fours.”

Spencer never had a chance to even sit on the bike prior to Laguna, as his first laps were in practice for the race. The NR was unlike anything Spencer had ever ridden.

“It would idle at 6000 rpm,” Spencer said with a smile. “It was a weird feeling riding it. It didn’t have enough weight on the front. It felt like it had a very little engine turning way up in the rpm range. The powerband was supposed to be from 13,000 to around 19 to 20,000 rpm, but no… it wasn’t torquey enough to run well at the lower rpm. I geared it to where I was shifting it all the time. I figure the powerband that worked for me was 18 to 21,000, so I was over-revving it a bit. We had no rev-limiters back then.”

By the second session, Spencer was figuring out how to ride the NR. He was making it work by wringing the little NR’s neck.

In practice, Spencer’s times on the NR were promising, but no one—not even those in the Honda camp—could have dreamed what would happen in the heat race.

“It was only five laps,” Spencer said. “I figured anything could hold together for five laps. I knew the only hope of beating Kenny [Roberts] was to push the bike past its limits. They told me not to rev it over 20 and a half, but I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could win something on this bike?’ So, I revved to 21 to 21-and-a-half, running down the hill that is now Rainey [Corner]. There was no way I could have been competitive against the two-strokes had I ran the thing down around 13 to 14,000 rpm.”

Spencer somehow made the bike last and rode the NR to a jaw-dropping victory over “King Kenny” Roberts. The win reverberated across the Pacific, all the way to Honda headquarters in Japan.

“You talk about excited,” Freddie recounted. “The Japanese engineers were jumping up and down and people were running off to call Japan. You would have thought I’d won the World Championship or something. They were so excited, they said, ‘Let’s pack it up and go to Silverstone.’”

It almost didn’t matter that the NR didn’t make the finish of either race in Laguna’s doubleheader. Like a gambler who’d hit big once in Las Vegas, Honda clung to Spencer’s heat-race victory over Roberts like a kudzu to a Georgia oak.

Just a few short weeks after Laguna, Spencer was flown to England to race the NR in the British GP at Silverstone. The NR wasn’t going to the museum after all; Honda thought it had finally found the man who could win on the bike.

The trip to England didn’t go according to plan. On Spencer’s first try at bump-starting the bike, he jumped too high and landed on the tank with a thud, bruising his chest in the process. They practiced dozens of times until Freddie could start the bike in just two big steps.

On the track, Spencer found the NR’s lack of torque almost humorous.

“Silverstone—big racetrack, tall gearing,” Spencer said. “I’d come off the left-hander onto to Hanger Straight and there’d be a slight breeze, and I’d shift the thing and it would drop rpm. I’d learn to tuck in everything. I think I qualified pretty well, maybe top 10. In the race, I ran maybe fifth or sixth and in the points but then the valve springs began to disintegrate.”

After Silverstone, the stark reality hit Honda like a ton of bricks. It was plain to see that Honda had the most talented young road racer in the world in Spencer, but even Fast Freddie couldn’t work miracles with the NR.

Even before Spencer temporarily breathed new hope into the NR program, Honda had its contingency plan in the wings: the three-cylinder two-stroke NS500. Two years later, Spencer would be World Champion on the four-cylinder, two-stroke Honda NSR500.

“As the years have gone on,” Spencer said, “the main thing about riding the NR was that I was happy to see all the Honda people so happy with that Laguna heat-race win. They were so frustrated after pouring so much effort into the bike and getting no results that when I beat Kenny, they were on top of the world, even if it was for just a short time.” CN