Larry Lawrence | July 25, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the June 2, 2010 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

The Sultan Of Soil

Faces were sullen on the morning of April 11, 1975 at Texas Stadium as a steady rain all week had turned Pace Motor Sport’s $50,000 investment in dirt into a soupy brown mess. The successful promoters of the Houston Short Track and TT Nationals decided to bring the AMA Grand National show to the Dallas suburb of Irving, Texas, and the home of the Dallas Cowboys. Although Texas Stadium had just enough of a roof to protect the fans, the problem was the 2 1/2-acre hole smack-dab in the middle that left the field exposed. Things were looking grim. Amateur flat trackers were slated to take to the track that night followed by the pros the next day.

West Coast track-prep wizard Harold Murrell assessed the situation and then went into action. No one dreamed the track could be made raceable, but Murrell wasn’t going to throw in the towel. Instead, he tossed in 21 dump-truck loads of sand, 26 tons of dry concrete, and enough calcium chloride to clear the streets of a Buffalo blizzard. Murrell then kneaded the whole concoction like so much pizza dough, and laid out a track that was race-worthy—rough for sure, but race-worthy nevertheless. Murrell had saved the day—for the promoter, for the fans and for the racers, who had traveled from all across the country to get there to race. Kenny Roberts won the Dallas Short Track National on Saturday over Randy Cleek on a much-improved track, and Murrell was a hero.

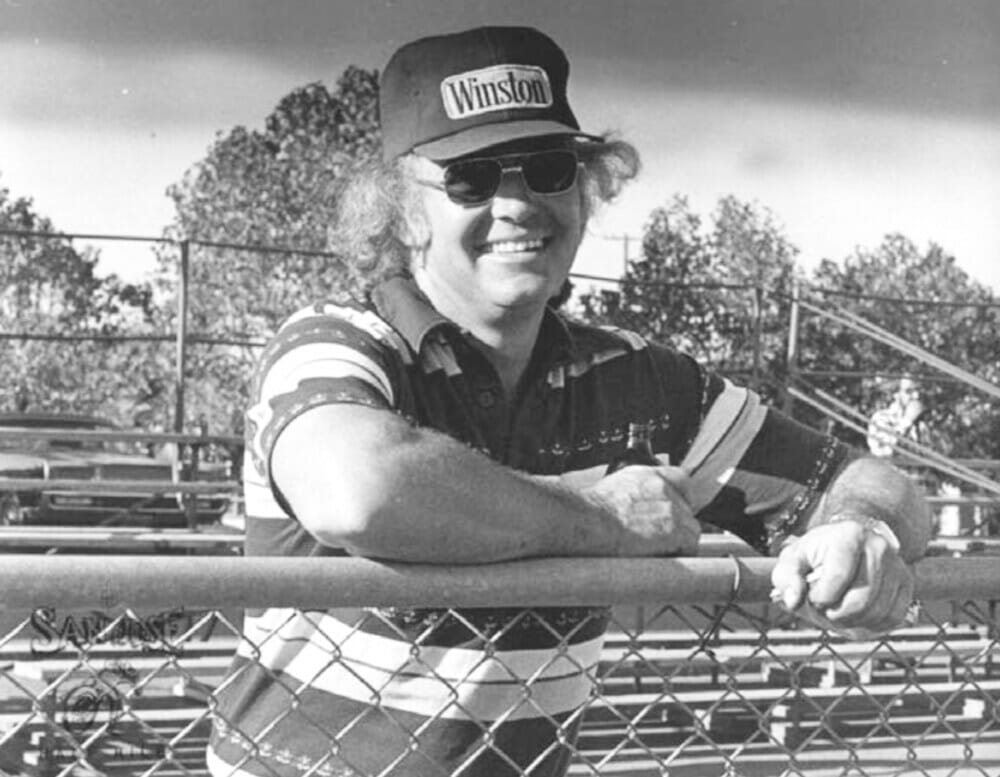

Harold Murrell’s favorite work was prepping the soil for the San Jose Mile.

Harold Murrell’s favorite work was prepping the soil for the San Jose Mile.

Murrell was born in Oklahoma, but like tens of thousands of Okies before him, he ended up in sunny California, specifically Fresno. As a young man, Murrell got into motorcycles and started participating in field meets and became a leading off-road racer in his district.

The fact that Murrell became the nation’s master track builder happened by sheer chance. Had it not been for a grader operator with a particular taste for the bottle, Murrell said he might have been a suit-and-tie man.

“I had a little dirt track in Selma, and I didn’t know how to run a road grader,” Murrell said in a 1979 interview with the Oakland Tribune. “But I had a problem with my grader operator. He was a wino. One day he didn’t show up and I said ‘Hey, I’m going to learn how to do this, because I sure can’t depend on him.’”

That was in the late 1950s, and, within a decade, Murrell’s skill at prepping a flat track put him in demand at dirt tracks all across the West Coast. When stadium racing began in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Murrell was the go-to guy. Choosing to learn to operate that grader led to Murrell traveling all across the country, and even the world, to build motorcycle (and occasionally stock-car) dirt racetracks.

Murrell’s dirt-racing surfaces were so predictable they were legendary. He got so good at understanding various forms of sands, silts and clays that he began receiving packages of dirt from frustrated dirt-track owners pleading for him to figure out how to make their tracks better.

“We mix it with water and calcium chloride,” Murrell explained. “We do that to see how it holds the moisture. Most people have decent soil… they just don’t know how to treat it. With our experience, we can look at the dirt and tell them what to do with it.”

There was the occasional misfire: At the infamous 1979 Oakland Supercross, the track was so sandy that Jimmy Weinert won the thing using a sand-dune tire on the rear of his Kawasaki. That was Murrell’s track. But for the most part, Harold had a knack for mixing just the right ingredients to make a track hold together. He was renowned for building tracks for indoor stadiums. Murrell prepared courses at the Astrodome in Houston, Kingdome in Seattle, Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan, and the Olympic Stadium in Montreal. When Japan held one of its first Supercross Invitationals in Tokyo, Murrell was flown in to build the track.

Lifelong friend Doug Wilson said he never saw anyone who worked so hard.

“That dirt had to be out of the stadiums, and I saw Harold work 30 straight hours to get the job done,” Wilson remembers.

Murrell learned how to operate the grader on the job.

Murrell learned how to operate the grader on the job.

For all the talent Murrell had at building Supercross tracks, he was perhaps the proudest of his flat tracks, specifically the San Jose Mile. San Jose became one of the premier Miles on the AMA calendar and many attributed that to the nice racey surface that always greeted the riders every year. San Jose gave riders multiple racing lines and often produced some of the closest finishes of the AMA Grand National season.

According to photographer Dan Mahony, Murrell always had a few riders out on the track on the day before the Sunday National to check out the track’s surface. One of the most interesting pre-rides came in the mid-1980s. The Harley-Davidson factory team was there, and Mark Brelsford, then 10 years retired, pondered about how the XR750s handled (they were still struggling with the new motor when Mark retired) with the then-new wide Goodyear tires. Somebody said, “You wanna take a spin?” and Mark jumped at the chance. So, with no practice, no leathers, and not even a steel shoe, Mark borrowed a helmet and promptly cut some laps within sight of the track record.

Chris Carr, who was just coming into the sport during that era, remembers San Jose as being perhaps the best-prepped track of the season.

“San Jose wasn’t that wide to begin with, but Harold always managed to make a groove that was a mile wide,” Carr said of the famous Mile. “Those tracks were table-top smooth and everyone always looked forward to racing there.”

Murrell worked until cancer made him too sick to continue and he passed away in 1999. Before he died, Harold was asked about the work of digging in the dirt that seemingly chose him, instead of the other way around. Murrell approached the question with a sense of humor.

“I don’t particularly like it,” Murrell said of his job. “It’s work. And it’s hard work. Heck, I can remember when I was almost an executive, and all of a sudden I got in the dirt business.” CN