Larry Lawrence | May 16, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from the August 5, 2009 issue. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Harley’s First Factory Rider

The lineage of Harley-Davidson factory racers goes directly back from Kenny Coolbeth, to Scott Parker, to Jay Springsteen and so on, all the way back 95 years to Red Parkhurst, Harley-Davidson’s very first factory racer.

Red Parkhurst moved to Milwaukee and became the very first member of the Harley-Davidson team.

Red Parkhurst moved to Milwaukee and became the very first member of the Harley-Davidson team.

During its first decade of existence, Harley-Davidson purposely stayed out of racing. In fact, there is good evidence that one of the founders, Arthur Davidson, was dead set against racing. Indian was by far the leading manufacturer of motorcycles in the 1910s, and the company built its reputation in a large part from racing. Harley-Davidson took the opposite tactic, earning its standing by way of making motorcycles known for serviceability and a means of reliable transportation. But with Ford ratcheting up the production of its Model T, by the early Teens, motorcycles were already moving from the realm of cheap everyday transportation to more of a vehicle of recreation.

In addition to Indian, manufacturers like Thor, Cyclone, Merkel, Pope, Reading-Standard and others were all earning publicity through racing. Just because Harley-Davidson’s official stance was to stay out of racing, that didn’t mean all its customers paid attention. By 1913, private Harley-Davidson riders began to have success. A pair of riders named Ray Watkins and Ben Torres set a speed record on a Harley in 1913, and the company produced its first win ad. The ad pointed out that the record was a complete surprise to Harley-Davidson and they in no way sanctioned the record run, but they touted the accomplishment, nevertheless.

In the background, The Motor Company hired Bill Ottaway from Thor. Ottaway had been the engineer behind Thor’s very successful racers of the early Teens. Quietly, Ottaway began building and testing racing machines. There is some debate as to whether Parkhurst or Irving Janke was the first factory racer for Harley-Davidson. The distinction is that Janke was a Harley- Davidson employee to begin with and was more or less a test rider who raced as part of the testing process. Parkhurst seems to be the first person hired specifically as a factory racer.

Parkhurst was born in Rapid City, South Dakota, in 1895. He moved with his family to Denver as a child. His father was a railroad man and later owned a small brewery. It was not uncommon for youngsters to go to work in that era, and such was the case with Parkhurst. One of his first jobs was as a gofer for a painting company. He was often given the task of driving the company truck, full of painting supplies, to job sites around Denver. He didn’t last long on that job due to his propensity for speeding.

He later took a job at an Excelsior motorcycle dealership, learning to be a mechanic. Parkhurst pursued his love for speed and began racing motorcycles (after lying about his age) as an amateur at the age of 13. Riding his own Excelsiors, he established himself as one of the top Rocky Mountain Region riders and primarily raced on the Tuilleries Motordrome board track in Denver.

By the time he was 16, Parkhurst was doing well enough on the boards that he began racing at other motordromes across the Midwest. In 1914, Harley-Davidson, which, up to that point, had largely ignored national competition, was making plans to form a racing team. As it turned out, Parkhurst was in the right place at the right time. He had performed well at Milwaukee’s new motordrome and Harley-Davidson’s racing manager Bill Ottaway asked the 18-year-old rider to join the company’s new racing team. Parkhurst eagerly accepted, moved to Milwaukee, and became the very first member of the Harley-Davidson team.

Parkhurst passed away in 1972.

Parkhurst passed away in 1972.

With Parkhurst riding, Harley-Davidson tested its new racer at low-key regional races early in 1914 in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Parkhurst won most of these regional events against non-national competition. Testing continued through the 1914 season and the team entered the prestigious Dodge City 300 to assess the reliability of its machines in real racing conditions.

In 1915, Harley-Davidson’s racing team was ready and launched a serious assault on the big national events. Parkhurst’s teammate, Otto Walker, was the star of the year, winning the big events at Venice, California (where Parkhurst was second) and Dodge City. But later in the season, Parkhurst started making his mark, winning several events including the big 100-mile National on the dirt track in Saratoga, New York.

A lavish new two-mile motordrome had been built in the Sheepshead Bay region of Brooklyn, New York. The FAM hosted a National Championship event at Sheepshead Bay in 1916 on the same date as the Dodge City Classic. Harley-Davidson decided to send board-track expert Parkhurst to New York instead of Dodge City. Parkhurst easily won the 100-mile FAM National Championship in front of the massive grandstands that were packed with 18,000 fans—perhaps the largest crowd to see a motorcycle race up to that point.

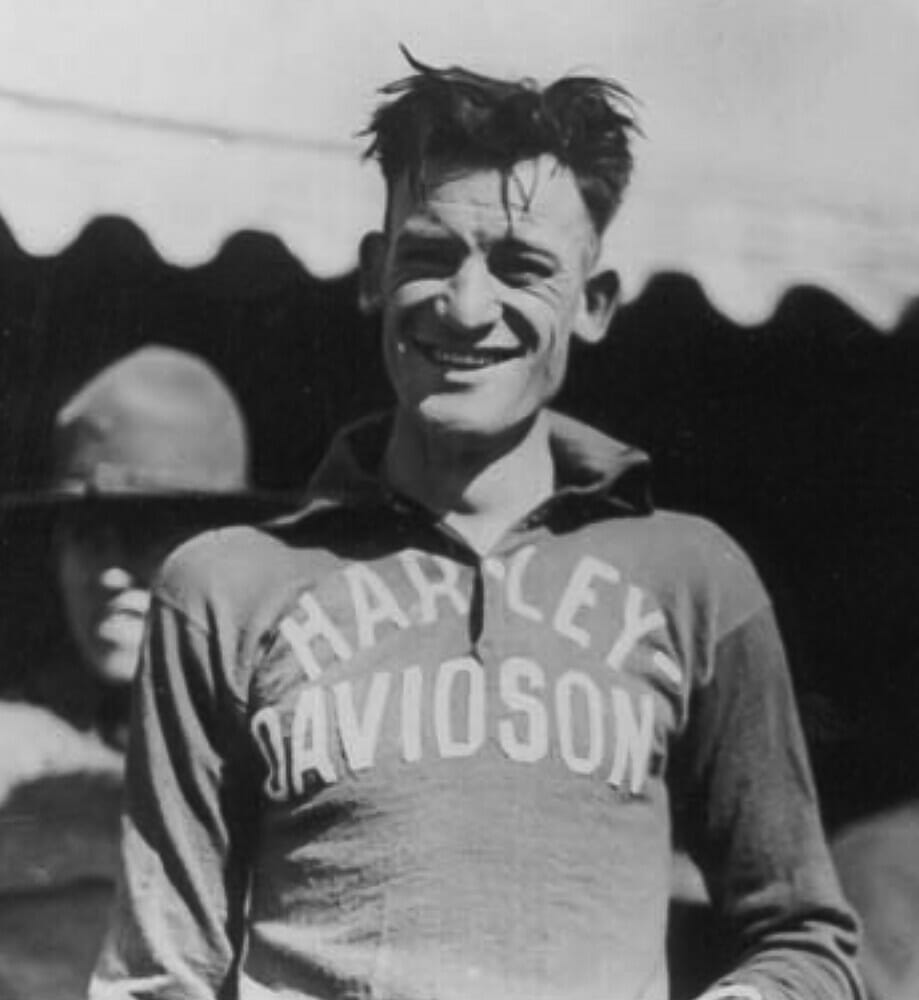

In magazine articles, Parkhurst was often noted as always having a big smile and being one of the crowd favorites. He was said to shine on rough tracks. At 6-foot-4-inches tall, topped by a thick head of red hair (thus, the nickname “Red”), he cut a rather imposing image when standing next to the mainly diminutive community of motorcycle racers. Harley-Davidson used images of a smiling Parkhurst in countless race ads during the mid-to-late 1910s. He became a true sports celebrity. One of Parkhurst’s good friends and biggest fans was fellow Coloradoan Jack Dempsey, the World Heavyweight Boxing Champion.

During World War I, Parkhurst stayed in Milwaukee and worked as a truck mechanic.

After the war, Parkhurst was asked to rejoin Harley-Davidson’s racing team. One of the first big nationals after the war was the 200-miler held in June of 1919 at Ascot Park in Los Angeles. Parkhurst made a solid return to the track with a second-place finish behind teammate Ralph Hepburn.

In September of that year, Parkhurst earned his biggest victory in the 200-mile road race held in Marion, Indiana. With the Dodge City race not held in 1919, the Marion race (now run under the auspices of the newly formed Motorcycle and Allied Trades Association—M&ATA—taking over from the defunct FAM) became the biggest race of the year, with 18 factory riders from Harley-Davidson, Indian and Excelsior. Parkhurst took over the lead of the race from teammate Otto Walker just past the halfway point. Indian’s Teddy Carroll threatened his lead late in the event, but Carroll’s bike broke a valve with just two laps to go and Parkhurst went on to victory. Hepburn and Walker took second and third to make it a clean sweep for Harley-Davidson.

In February of 1920, Harley-Davidson went to Daytona Beach and Parkhurst set a number of short-lived speed records. In June of that year, Harley-Davidson rented the Sheepshead Bay track (considered the fastest board track in the country) to attempt a 24-hour solo record. Parkhurst set a new distance record for 24 hours, covering 1452.75 miles, despite having to wait out two hours of hard rain, then riding on a very slick track as the boards dried out. Exhausted by the solo run, Parkhurst broke the existing mileage record with over an hour to go and could have pulled in, but bravely held on to complete 24 hours.

In 1921, Parkhurst took a job offer from Excelsior and became a Midwest sales rep for the company and raced for them, much to the chagrin of Harley loyalists. He had a miserable season with Excelsior and returned to racing Harleys in 1922. By this time, Parkhurst had a family and was no longer racing full time. He continued to race sporadically through 1924, earning a couple of podium finishes on his adopted hometown track, the Milwaukee Mile, at M&ATA and AMA Nationals held there in 1923 and ’24.

After retiring from racing, Parkhurst continued working in sales for companies such as Firestone and Valvoline. He retired in the 1960s and died in 1972 while living in Washington State. He was 76. CN