Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

America’s Suzuka

The Ontario 6 Hours—a.k.a. the American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM) 6 Hours—had a seven-year run and, in spite of annual scoring faux pas, it became the best-known endurance race in America. It was America’s own version of the Suzuka 8 Hours, if you will. Ontario, which ran from 1974 to 1980 in the spring, attracted many of the top riders and teams in the then burgeoning ranks of Superbike racing.

The race was held on Ontario Motor Speedway’s 3.2-mile road course, which, much like Daytona International Speedway, utilized part of an oval Superspeedway and an infield road-course section.

The first race was held in 1974 and was called the AFM 300. A team endurance race, the AFM 300 was won by the father-son team of Buddy and Mike Parriot on a Yoshimura Kawasaki, though it was Yvon Duhamel who was the star of that first race. After a gimpy LeMans start, Duhamel was last off the line. He blasted through the field on another Yoshimura Kawasaki Z-1, passing a remarkable 30 riders on the first lap alone. Four laps later, he blasted by early leader Reg Pridmore on the Butler and Smith BMW.

It looked as if Duhamel and teammate Pat Alexander would have the inaugural race in the bag, but a rear brake rod came loose, and Alexander crashed as he came into the pits. After falling behind making repairs, Duhamel again rallied the team and put them back in the lead until a cracked cylinder put them out for good.

That left the other Yoshimura entry of the Parriots alone in the lead. Pridmore made a late-race charge, but Mike Parriot was given the “EZ” sign from his crew and took the checkered flag with a 30-second cushion over Pridmore and teammate Marty Lunde.

The race officially got the 6 Hours designation in 1975. That year was one of attrition among the front runners. David Aldana, teaming with Mike Parriot, crashed the favored Yosh Kawasaki. Bob Endicott and Pat Evans had a crank break on their Z-1. The BMW of Reg Pridmore and Cook Neilson led a lot, but Neilson crashed when he ground through the Beemer’s rocker-box cover. Team Hansen’s blazing Laverda, with Keith Code and Lane Weil, got a flat tire, while Ron Pierce and Pat Lagan’s BMW had a series of troubles that put oil all over the rear tire.

Underdogs Martin Carney and Roger Hagie won the 1975 race on a box-stock Kawasaki Z-1 that had no oil showing in the crankcase window at the finish. The pair’s prize money was $485. Carney and Hagie were Kawasaki employees who “borrowed” a company bike to race in that very first 6 Hours.

Hagie remembers the strategy that won the first Ontario 6 Hours:

“Martin was a Brit with GP experience, so you know who was the faster,” Hagie says. “Endurance racing wasn’t very common in those days and a lot of teams came out and rode like they were in a sprint race. Martin and I just got into a nice smooth rhythm and eventually found our way to the front.”

Perhaps the biggest upset ever in the Ontario 6 Hours came in 1976. That year, Steve Mallonee and David Breetwor sneaked under the radar with a sweet-handling Triumph T160 Triple. As Breetwor described it, “All the hot rods blew up,” and he and Mallonee motored to victory by four laps over Wes Cooley and Mike Parriot on a Yoshimura Kawasaki that was some 30 mph faster in top speed than the winning Triumph.

“The original plan was to win the 750 Production class,” said Breetwor. “I did a lot of club racing there [at Ontario], and I knew that if we turned 2:23s we’d probably win our class. Mallonee was a little more aggressive than me and he was turning some really good laps, plus, we had our pit stops down to 25 seconds. I did okay until I found out we were leading the race and I started getting slower, I was so nervous. The headline came out after we won that said something about the tortoises beating the hares and that rubbed me the wrong way.”

The next year, 1977, was the year the race really came into its own. It was held in April, the dead spot on the AMA calendar after Daytona, and with all the publicity the race received, the factories decided it was a good showcase. That year, Yoshimura had a Kawasaki entry with Wes Cooley and Tony Murphy and a Suzuki entry with Pat Eagan, Terry Waugh and John Ulrich. AMA Superbike standouts Keith Code, Reg Pridmore and Cook Neilson piloted a Racecrafters Kawasaki KZ1000. Paul Ritter, who would go on two months later to win the Sears Point AMA Superbike National, was in the race on a Ducati with teammate Vance Breese. David Emde and Harry Klinzmann were on a Lester Wheels Kawasaki KZ1000 and defending Ontario 6 Hours winner David Breetwor teamed that year with Jim Haberlin.

A total of 82 bikes roared off the starting line at the ’77 race, with 45 bikes surviving what was becoming a six-hour sprint race. That year might best be remembered for the massive scoring confusion that seemed to always plague the event. Cooley and Murphy were originally declared the winners on a Yoshimura Kawasaki Z-1 and Cycle News’ coverage even heralded their victory. Four days later, the AFM issued a press release stating that Emde and Klinzmann were the actual winners on a Lester Wheels Kawasaki KZ1000. Cooley and Murphy were runners up.

The 1978 race ran in rainy conditions. Ritter, riding a Ducati 750, took over the lead on the fourth lap from Chuck Parme on a Z-1. Ritter and his Ducati were perfect in the rain. Despite pitting with water-caused ignition problems, Ritter was back into the lead when his bike retired for good at the 90-minute mark.

Hurley Wilvert and partner Dennis David may have well won the race, but the rain stopped and on a drying track Reg Pridmore (who teamed with Code and Pierre Des Roches) came flying past on the Vetter Kawasaki. Pridmore/Code won by eight seconds in spite of taking a 37-second gas stop with five minutes to go.

Kawasaki heralded the win with a full-page ad. However, new Cycle News Editor Charles Morey had not given the race feature coverage and he caught hell for it, highlighted by a scathing letter from Art Friedman and Jeff Karr of Cycle Guide magazine. Morey hit back saying he would be “watching for the in-depth, colorful coverage in Cycle Guide when it comes out in a few months.”

Ontario hit its peak in its final two years. Both the 1979 and 1980 fields were chock-full of factory and supports teams and their riders. It now featured a $10,000 purse. Morey, perhaps answering his critics, ran a full preview feature in Cycle News on the 6 Hours.

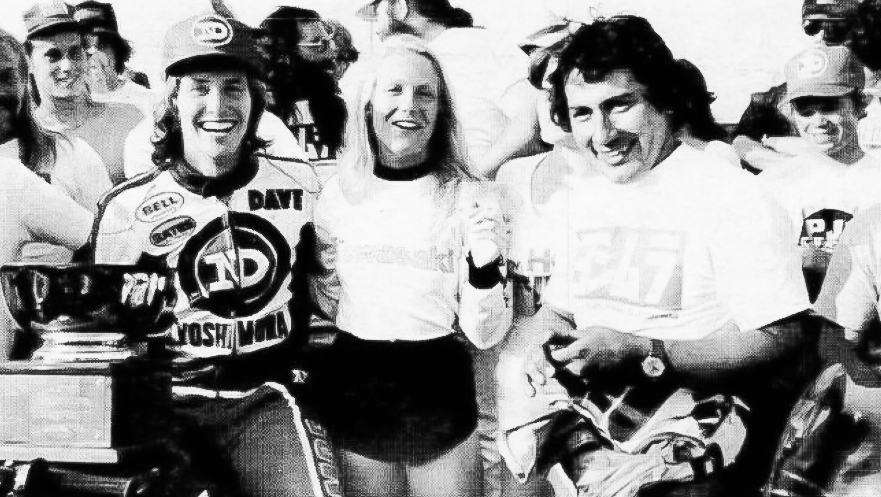

Aldana and Dave Emde won the 1979 edition on a Yoshimura Suzuki GS1000 with a rear tire that was down to the cords at the finish. The race was marked by a spectacular crash in which Bettencourt, riding the factory Kawasaki entry, was drafting the Yoshimura Speed Center Suzuki on the front straight. The Yosh bike suddenly whipped to the side and Bettencourt plowed into the back of a much slower running Yamaha RD400 at full song. The impact snapped the triple clamp of Bettencourt’s big Kawi in half. A red flag stopped the race and remarkably neither Bettencourt nor the Yamaha rider was seriously injured.

The final Ontario 6 Hours in 1980 unfortunately did not end in storybook fashion. The race was cut short by 20 minutes due to an ugly crash on the front straight-away that resulted in Bill Silver being taken away in a helicopter. Silver, while suffering broken bones, was not as bad as he looked lying sideways 10 feet off the racing line on the front straight, but those at the race did not know that and the race was called.

Scoring was backed up to the last full lap before the red flag and it showed the Honda CB750F factory superbike pair of Ron Pierce and Freddie Spencer (in his first visit to Ontario), having earned the victory over Team Kawasaki’s David Aldana and Eddie Lawson by—get this—one second!

Yoshimura Suzuki’s Wes Cooley qualified first that year with a track record time of 2:01. Lawson and Spencer also qualified under the lap record, setting the stage for the fastest 6 Hours in its history. A poor tire choice would hamper the Suzuki squad, however, so that meant a one-on-one battle was on between Honda and Kawasaki. Spencer vs. Lawson and Pierce vs. Aldana—a classic match-up.

When it was over, Honda was credited with the win, but Kawasaki protested the results claiming scoring missed one of their laps. It took nearly a week of looking over the scoring and pit entry/exit sheets to finally confirm Honda’s victory. The AFM, however, was under intense pressure with the Kawasaki protest and some evidence of the pit entry/exit logs pointed towards a Kawasaki victory—and a backdrop of both Honda and Kawasaki looking over their shoulder. In the end, AFM officials acknowledged that Kawasaki may have in fact won on the track but lost in the scoring tower by virtue of a Kawasaki’s own scorers mistake.

It was somewhat of an inauspicious ending to what had become one of the most popular road races of its era.

Ontario Motor Speedway was closed in 1980 and eventually leveled. Today, hotels and shopping centers occupy the grounds. CN

Click here to read the Archives Column in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Subscribe to nearly 50 years of Cycle News Archive issues

Click here for all the latest Road Racing news.