Cycle News Staff | April 4, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from issue #26, July 7, 2004. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

USA’s Return to Speedway Greatness

By Scott Rousseau

When Jack Milne stood atop the World Championship Speedway Final podium, ahead of fellow Americans Wilbur Lamoreaux and brother Cordy Milne in London’s Wembley Stadium on September 2, 1937, becoming the country’s first World Champion in motorsports, who could have known that he would also be speedway’s last American World Champion for the next 44 years?

But that’s how it went down. For over four decades after that historic and as yet unmatched American sweep in the World Championship, Americans were off kilter in the World Speedway scene. It would not be until the dawn of the 1980s that a new breed of Americans—California surfers, no less—would come along and restore America’s presence in the sport.

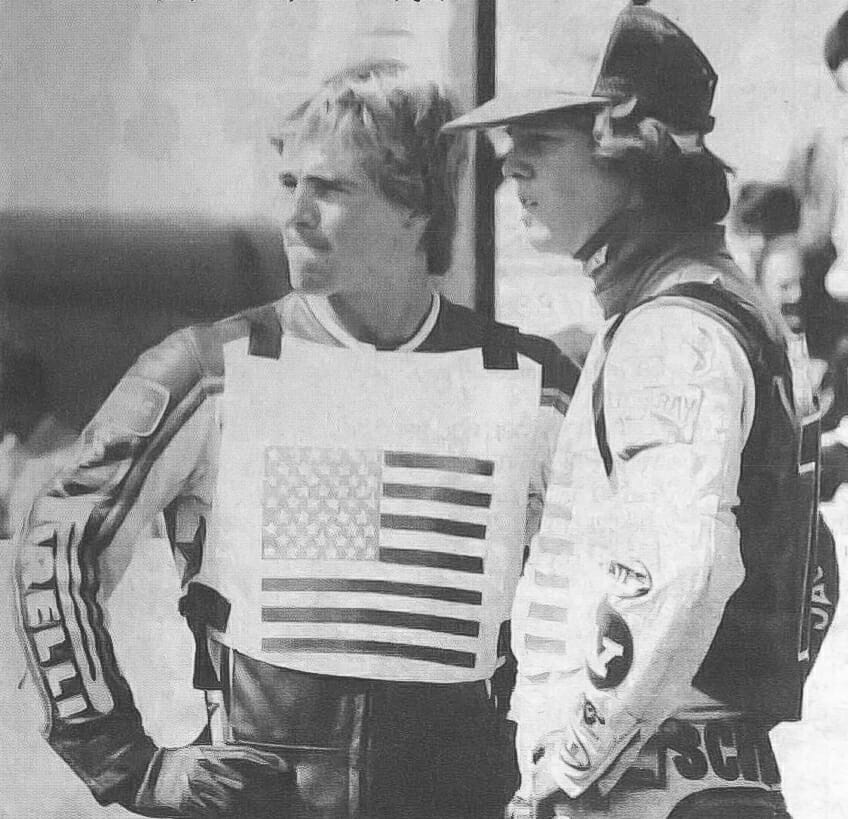

Bruce Penhall (left) and Bobby “Boogaloo” Schwartz won the World Best Pairs Speedway Championship in 1981, putting the USA back on the speedway map after a long hiatus.

Bruce Penhall (left) and Bobby “Boogaloo” Schwartz won the World Best Pairs Speedway Championship in 1981, putting the USA back on the speedway map after a long hiatus.

The seeds for the renaissance were actually sown back in 1969, when former World Champion Milne himself and an employee of his, an entrepreneurial lad named Harry Oxley, decided to start holding weekly speedway races at the Orange County Fairgrounds in Costa Mesa, California. Set on a gritty, groovy track not much bigger than an Olympic-sized swimming pool, a stone’s throw away from the Pacific Ocean, Costa Mesa was light years from the prim and proper European scene replete with its high-dollar professional leagues and groomed-from-youth World Champions-elect.

Yet, like the fabled astronaut movie of the same name, Costa Mesa somehow attracted the guys with “the right stuff.” Maybe it was the close proximity to the beach, maybe it was the sheer excitement of taming an unrideable 50-horsepower, 180-pound, alcohol-burning missile of a motorcycle with no brakes, maybe it was the lure of the kind of money that you couldn’t even make with a real day job back then, but the surfers started trading in their wetstuits for leathers when the summer sun went down, and a new era of professional American speedway racers was born.

For the first seven years, America had nothing for the world, but then along came Scott Autrey’s brilliant third-place performance in the 1978 World Final, followed by Kelly Moran’s fourth place in ’79. The man who would become American speedway’s golden boy of the era, Bruce Penhall, suffered a disappointing fifth in 1980, a season that held high hopes for an American victory.

But 1981 was to be Penhall’s year—and not just his alone, as he and fellow American Bobby “Boogaloo” Schwartz really got the ball rolling in Katowice, Poland, on June 21 of that year. Before 70,000 fans at the World Best Pairs Final, the pair out-pointed the best in the world. The Americans thoroughly dominated the event, although their score, 23 points against 22 by New Zealand and 21 by Poland, doesn’t reflect it.

“We had never ridden the track before, and when we got there, it was raining, and we never got to practice,” Schwartz remembers. “Then what happened was that we were getting a 5-1 while we were leading the Germans when Bruce’s bike blew up. I went ahead and won the race to make it 3-3.”

In their next heat, Schwartz remembers, the unthinkable happened to Germany.

“In their next race both the Germans got taken out in the same crash, and they had to bring in two reserves, and basically everybody that raced the Germans after that got a 5-1 automatically, while we had only gotten a 3-3 against them. The score shows that we only won by one point, but it should have been more.”

Especially when the Americans found out that the cards were unscrupulously stacked against them.

“I don’t even know that I should be saying this now, but I remember that was also a year that the Danes were going to try and help the Poles win it as repayment for giving the Danes some help at a race the year before,” Schwartz said. “I found out about it, and I went to Hans Nielsen and told him, ‘Whatever they’re giving you, we’ll double it.’ Of course, we never intended to pay him anything, but the point was that I was telling Nielsen to do the right thing.

In their heat against the Poles, Ole Olsen came off the start last—and he never did that—but Nielsen led it, and I kept waiting for him to pull off. But he did do the right thing, and we won it.” Penhall would go on to win the World Final before 90,000 screaming fans at Wembley that year, his exploits well chronicled in a national television broadcast by CBS. In 1982, Team USA built on that success by going on to win all there was to win, taking the World Best Pairs and the World Team Cup, with Penhall repeating as World Champion in a controversial World Final at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Schwartz was the top performer in the two team events, running unbeaten in the World Best Pairs and the World Team Cup (though he unselfishly passed up a chance for a maximum score by giving teammate Autrey a substitute ride in his final event after the title was in the bag).

“It was such a time for us, and it has never been like that since,” Schwartz says. “We were all just virgins, digging it and believing that we could do it because we didn’t know any better. It was like we came from this tight little track with a ton of dirt on it, and then when we went over to those big tracks, well, you could have a cheese sandwich because there was so much room. It wasn’t easy, though, and half the time we struggled just to find our way to the tracks. There were like three McDonalds over there.

“But it was just a special time, not just for Bruce and me, but for all 13 members of Team USA. We were into it, and we were having fun. It was a fantastic thing.” CN