Cycle News Staff | March 7, 2021

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives Column is reprinted from issue #14, April 14, 2004. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. So, to prevent that from happening, in the future, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Time And Untimeliness

By Scott Rousseau

Although Yamaha’s soon-to-be-all-conquering TZ700/750 four-cylinder project was in the pipe, it wasn’t ready for the 1973 road-racing season, so Yamaha elected to continue with its 350cc twin program against the much larger Kawasakis and Suzukis in AMA Grand National road racing as the season-opening Daytona 200 loomed.

Don Emde’s win aboard a Yamaha 350 had seemed to be a case of David among Goliaths in the 1972 Daytona race, and yet David prevailed. For ’73, however, the Goliaths were returning, and they were bringing friends. Kawasaki would field no fewer than six factory riders aboard its potent 750cc triples, including former Daytona winner Gary Nixon, Yvon Duhamel, Cliff Carr and Hurley Wilvert. Suzuki had four riders, with New Zealand Champion Geoff Perry and Emde as its top runners.

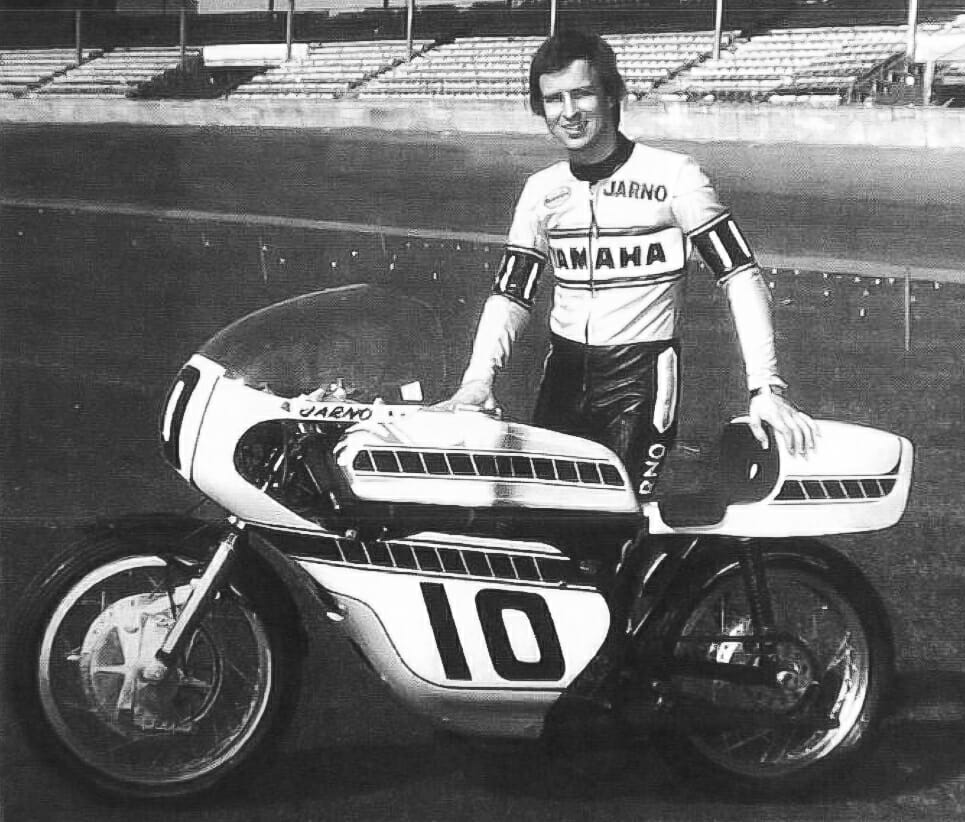

In terms of technological advances, Yamaha elected to play it closer to the vest, introducing water-cooled versions of the TZ350, but the ace up Yamaha’s sleeve would come in the person of Finnish road racing sensation Jarno Saarinen, the 1972 250cc World Champion, destined to meet with an untimely death little more than two months later.

Responsibility for the preparation of all the Yamaha road-racing machines, including the 250cc bikes to be run in the International lightweight 100K, fell on the shoulders of one man, 1969 250cc World Champion Kel Carruthers, who had come to wear several hats for the company since moving to the United States on a permanent basis in 1971. By 1973, the Australian was Yamaha’s race team manager, crew chief, rider coach and factory racer. As if preparing the quiver of factory bikes for stateside factory riders Kenny Roberts, Don Castro and Gary Fisher wasn’t enough, Carruthers also had to get a machine ready for the 27-year-old Finn. It made for a busy time in Carruthers’ EI Cajon, California race shop, as he recalls.

“I had my regular guys, and then Saarinen came over,” Carruthers says. “I don’t know how it happened, who instigated it, whether Japan wanted him to come or America wanted him to come. I was just told that he was coming, and could we provide him a bike. Everybody had a spare bike, so that wasn’t a problem. Fortunately, he brought over his own mechanic, which helped, because I was a little bit understaffed, to be honest.”

So much so that Carruthers almost backed out of the race himself because he was running out of time.

“I was just so busy running the race team that I had barely practiced,” Carruthers remembers. “I was working until late every night with the mechanics because I used to work on all the engines and everything. By race day, I was completely buggered, to be honest with you. That morning I helped them set up the fuel rig, so I never did go out for the Sunday morning practice session, and then one of my guys had trouble with a fuel cell or something. I just said to Jan, my wife, ‘I don’t even feel like riding. I’ll just take whatever off my bike and put it on his.’ But she talked me into riding. She said, ‘Just go out there and ride around. If you feel like you can do it, go on, and if not just pull in.’ So that’s what I did.”

It looked as though the Yamaha boys might all be out for a Sunday ride-along, as the big Kawasakis of Duhamel, Art Baumann and Nixon left the field behind quickly. But time was not kind to them. Duhamel and Baumann both crashed on lap nine, moving Nixon into the lead. Nixon only lasted another 10 laps before he was out with engine trouble. Then Suzuki’s Geoff Perry of New Zealand led for a brief time before ignition woes ended his chances. Fisher was the first Yamaha atop the leaderboard, but then he pitted for gas and lost the lead. A blown crank left him parked by lap 30. Suzuki’s Ron Grant held the lead after that, but, like teammate Perry, his ignition let go, dropping him out of the hunt.

The talented Saarinen quietly made his way into the lead on lap 32 and went on to run up front for the rest of the time, taking the win. Carruthers slipped into second place for what would be his best Daytona 200 finish. For the second year in a row, Yamahas ruled the podium, as Mel Dinesen-backed Jim Evans came home third.

“I wasn’t really aware of what was going on in front of me,” Carruthers says. “I wasn’t totally with it, to be honest with you. But then I looked up at the leaderboard, and I was up to second, and by the time I realized that, Jarno was too far gone. He was good. I’d raced against him in Europe. I think that he probably would have been 500cc World Champion that year.”

So, it would seem. After winning Daytona and also the prestigious Imola 200 in Italy, Saarinen then defeated reigning 500cc World Champion Giacomo Agostini in the 500cc French Grand Prix and collected another 500cc win in Germany. He was also well on the way to defending his 250cc title, having posted three wins prior to the Monza, Italy, round on May 20, 1973.

But that was when time caught up with Jarno Saarinen. On the first lap of the Monza race, Italian superstar Renzo Pasolini slipped in oil that had been left by a rider from the 350cc event held just prior. Saarinen could not avoid him. The ensuing pileup involved over a dozen riders, and Pasolini and Saarinen were both killed in one of the most tragic crashes in GP history.

Saarinen was gone, but it could be argued that he certainly made the most of his time while he was here.CN