Alan Cathcart | September 9, 2020

The late Colin Seeley was a pivotal force in the close-fought British short circuit racing scene of the 1960s, originally as a GP-winning sidecar driver, then top-level chassis manufacturer, and finally the builder of complete race bikes, engines and all, after he purchased the manufacturing rights and tooling for the Matchless G50/AJS 7R/Manx Norton GP racers from Associated Motor Cycles’ liquidators in 1966.

But Seeley’s organizational talents extended into other areas, from running a successful charity—the Joan Seeley Pain Relief Trust he founded in 1979, after his first wife succumbed to bone cancer—to managing the British Superbike title-winning Duckhams Norton race team, producing trials bikes and street motorcycles for Honda Britain to retail, and writing a two-volume autobiography recounting all this in quite some detail.

Those two massive and thus expensive books published in 2006-08 cried out for a good editor to cut back on much of the text covering races and events that didn’t involve Seeley bikes or riders. But the rest was packed with fascinating details about Colin’s life on two, three and, during a brief but troubled liaison with Formula 1 despot Bernie Ecclestone, four wheels. Their cost, coupled with the frustration of sorting such wheat as how Seeley came to design race frames for the Ducati factory, from the chaff of reporting on 50/125cc GP races for which he never made a single bike, deterred many classic race fans from finding out more about one of the seminal figures in British road racing by purchasing those books. But now a much more accessible portrait has been published of Seeley, an energetic, courteous but driven individual for whom the glass was perpetually half full, and who passed away last January soon after his 84th birthday, after a lifetime of achievement.

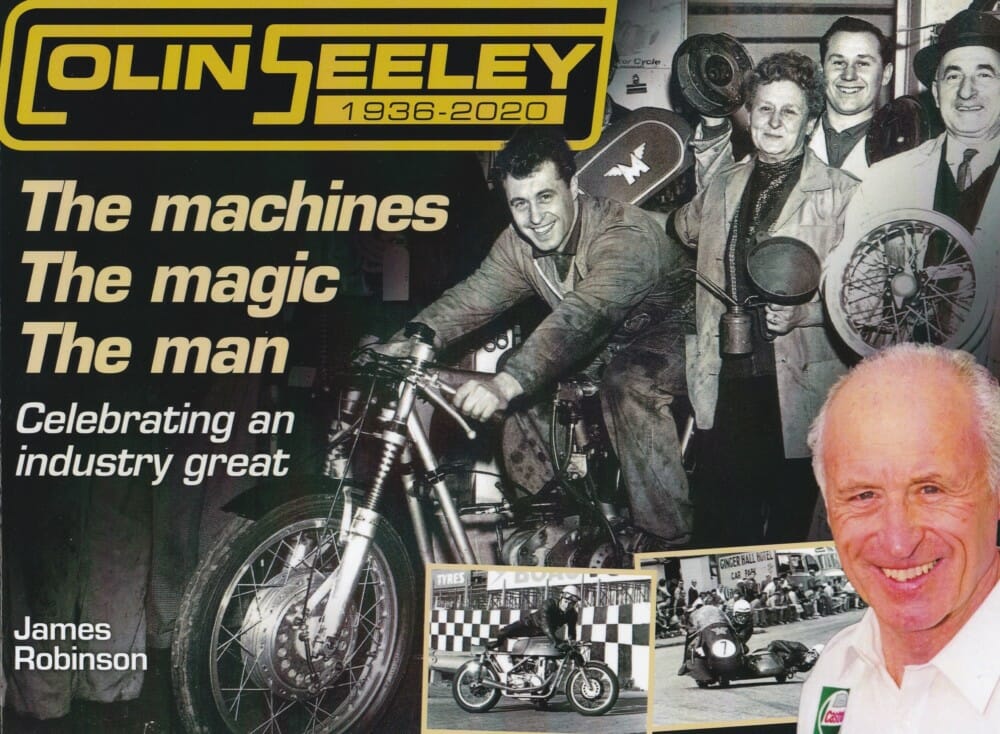

James Robinson’s Colin Seeley – The Machines, The Magic, The Man is a small 50-page book packed with 40 well-chosen photos of Seeley’s creations, and a perceptive chronicle of his career by Robinson, editor of The Classic Motor Cycle since 2003. Though short and inevitably lacking in any great technical detail, Robinson’s chapters cover the different aspects of Seeley’s career very adequately, providing a pen picture of the several different elements of Colin’s energetic existence. It summarizes very well the achievements of a man who left school without any qualifications beyond an aptitude for metalwork, and all things mechanical, yet who opened his own motorcycle dealership in Belvedere, Kent at the age of 20, retailing Matchless, AJS and Greeves models successfully en route to greater things.

The proximity of Colin Seeley Motorcycles to the Brands Hatch circuit inevitably led to its boss swapping his earlier dirt bikes for road racers, but of the three-wheeled variety with long-time friend and employee Wally Rawlings as passenger. Robinson recounts Seeley’s successful march to the top table of sidecar racing very well, but the space devoted to his establishing and running Colin Seeley Race Developments/CSRD from 1965-73 is frustratingly short. There’s surprisingly no coverage of the Seeley frames—one of them an avant-garde monocoque design—that CSRD provided the factory Suzuki race team with to cure the handling problems of the early “flexi-flyer” 750 triples, thus allowing Barry Sheene to win races and titles for the Japanese firm. There’s also a very evident gap in the narrative between the 1971 creation of the Seeley Mark IV race frame and the mid-70s Seeley-Honda road bikes, as if concern about attracting the attention of Bernie Ecclestone’s lawyers may have dissuaded Mortons, the book’s publisher, from even mentioning his name in connection with the 1973 demise of CSRD, in which the man Seeley had known from when they were neighboring rivals as motorcycle dealers undoubtedly played a part. But the role Seeley played in establishing and managing the Duckhams Norton Superbike team in 1992-94 to BSB championship success is well covered, and the success the team achieved was one of his greater personal achievements.

But Colin’s affinity with motorcycles all his life after learning to ride on his father’s pre-war Vincent Rapide, on which he passed his test aged 16, comes over loud and clear, and the photos alone are well worth this book’s modest price. It’s a fitting tribute to a man who overcame his humble beginnings to play a key role in the Classic era of motorcycle sport. CN