Cycle News Staff | August 9, 2020

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives edition is reprinted from issue #33, August 24, 2005. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. To prevent that from happening, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Gone But Never Forgotten

By Scott Rousseau

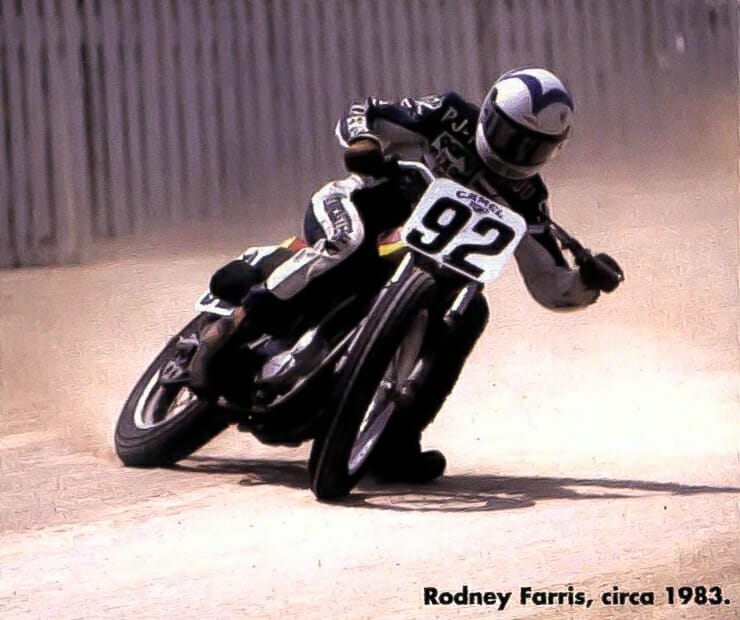

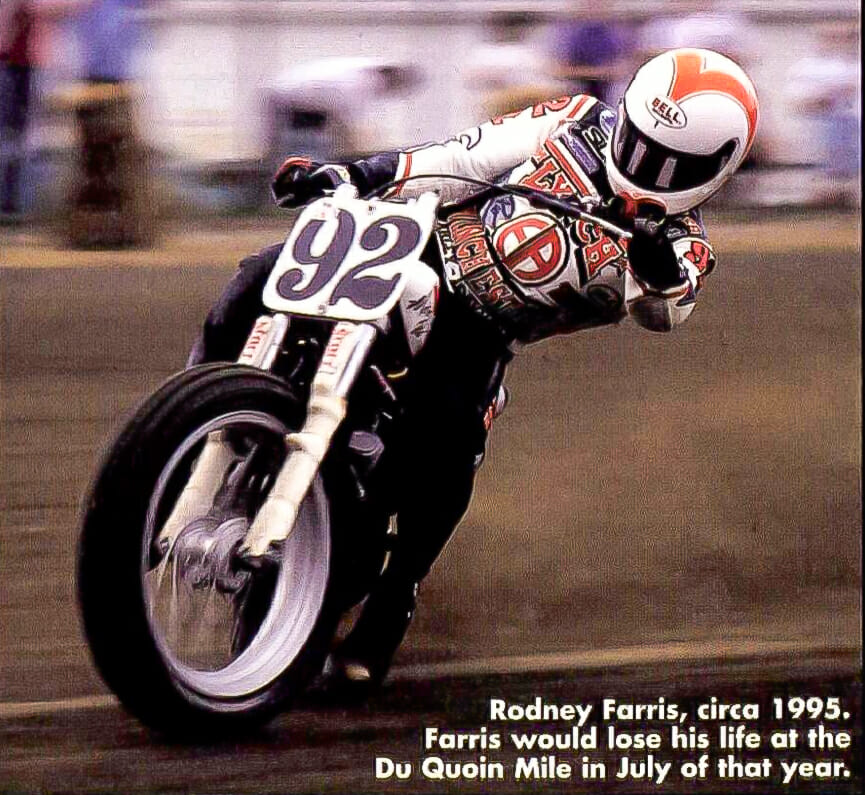

I was looking through some color slides nestled among the vast, barely charted wasteland that is the Cycle News photo-archive department the other day when I came across the circa-1983 photo of Rodney Farris that you see here. Then, almost immediately, I happened across the second one, which shows him racing in 1995. The wheels in my memory started turning, so I went to the 1995 edition of our bound volumes and looked up the July 2, 1995 Du Quoin Mile, the race where Farris lost his life. “God,” I thought out loud. “Was that really 10 years ago already?”

So, I picked up the phone, and I called Eddie Adkins, the man for whom Farris rode off and on, and for whom he was riding at Du Quoin that day.

“Hey, Ed,” I asked, “did you realize that it’s 10 years ago since we lost Rodney?”

“Yes,” he responded immediately. “July the second.”

The reasons for this revelation about Rodney Farris are ones that I’d rather not have to offer to anyone, but I’ll tell the truth, just as I told it in a column I wrote shortly after his death: I didn’t know him that well.

Another truth, and here’s the tougher one: Rodney Farris was the first man that I ever saw die. It happened in between turns three and four at Du Quoin on a beautifully sunny summer day during the best mile dirt track race I have yet seen in my years of covering dirt track for Cycle News. Just as he should have and just as he always did, Farris was trying to win the race when the crash happened on lap 17. Running the highest possible line on a freak Du Quoin racetrack that had traction from top to bottom, he clipped a hay bale and crashed. He was then struck by another rider, suffering a head injury from which he would not recover, and he was actually pronounced dead the next day, July 3. But that’s the stuff I already know. What I didn’t know was Rodney Farris, so I called Adkins, the one man who probably knew him better than anybody.

“So, tell me about Rodney,” I said.

“Well, I knew his father, Norman, before he was born,” Adkins said. “When Rodney came along, he was pretty much raised by his father, and we both saw a lot of his father in him. I first noticed his racing when he was about 9 years old.”

Rodney and the Adkins family bonded immediately.

“My wife actually wanted to adopt him,” Adkins said. “He was in an accident when he was an amateur, and he was in a coma for four days. When he came out of it, she talked to him on the phone every day, and she told me, ‘I want you to see what we can do about adopting him.’ I told her that we couldn’t do that, although much later I told Norman about it, and he told me that he would have been in agreement with that.”

Of course, Rodney rode for Adkins off and on throughout his career, a total of eight years.

“He rode for a lot of people,” Adkins said. “You know how it is. A kid will think that the grass is greener somewhere else, so then he goes there to find out.”

The thing is, with Adkins, that doesn’t carry much weight. The door to his racing stable has never swung both ways—save for one man.

“It did for Rodney Farris,” Adkins said. “Rodney was family. Everybody liked Rodney. I can’t recall anybody who didn’t.”

There are two things that I recall about Rodney Farris. The first is that he had a handshake like a vise, and if you just offered him your hand without paying attention, he would damn near try to break it just to get your attention, a smile on his face the whole time. The second is that he charged as hard as anybody I’ve ever seen, a memory that Adkins more than backs up.

“Rodney was not one to slow down to go fast,” Adkins said. “He was always full tilt.”

Adkins’ admitted that sometimes that wide-open attitude spilled into his personal life, and Rodney actually got mixed up with drugs in the middle of his career. It is worth bringing up only to say that he wised up and turned his life around. I didn’t know anything about that. I didn’t know him that well.

What I did know of Rodney was the same thing that I see in a lot of talented privateers: an intense focus, drive and desire to win. This first started to really show in 1993 and 1994, when he finished fifth in the AMA Grand National standings both years. Come 1995, when I first started covering the AMA series as a green-behind-the-gills dirt-track reporter, I watched him ride with the kind of authority that would lead you to believe that he had won several Nationals, even though he had never won one. Adkins remembered that but for bad luck, he would have won several. “He led Parkersburg right up to the last lap two years in a row, and one year we broke a coil bracket and the next year we split an oil tank,” Adkins recalled.

I vividly remember him being a real threat at the Memorial Day Springfield Mile in 1995 as well. Come about lap 15 at Du Quoin on July 2, I was convinced that it was going to be Rodney Farris’ turn to win. Adkins remembered that, too.

“At Du Quoin, I swear that he was going to win,” Adkins said. “At the time, he had led more laps across the finish line than anybody, and he was at a point that day where he had practiced both our motorcycles and told me that he could win on either one of them. He was upbeat.”

Instead, two laps later, it was Rodney’s time to leave. As I spoke with Adkins, he discussed the emotions that he felt then and since that day at Du Quoin, but regret was not among them.

“If I had told Rodney that day, ‘Hey, let’s put this stuff in the truck and go home,’ He would have told me, ‘Well, you can do that if you want to. I’m going to find something to ride.’ He was going to race no matter what. That was what he knew. That was who he was. I’m a firm believer that when you come into this world, your ticket is punched and you’re going to leave on time. Rodney wanted to race, and he wanted to win. He believed he could, and that’s what he was doing at the time. What happened was certainly nobody’s fault.”

I felt a little better after talking to Adkins, who admits that not a day goes by that he doesn’t think of Rodney. I must admit not sharing Adkins’ feelings about Rodney simply because I didn’t know Rodney that well, but I can tell you that not a day goes by that I don’t think about Will Davis or Davey Camlin or Andy Tresser, not a week without thinking of Aaron Creamer or Ricky Graham, people whom I knew very well. I know that’s the same for a lot of people.

I just thought it was important to take this time to remember that Rodney Farris has been gone for 10 years. I didn’t know him that well. Somehow, today, that makes me sad. CN