Alan Cathcart reviews SPEED: The One Genuinely Modern Pleasure by Mat Oxley.

Mat Oxley needs no introduction to today’s Grand Prix road-racing fans, as the writer with the inside track on what makes the sport tick, who’s on first-name terms with its leading practitioners of today and yesterday—riders, team owners, engineers and officials alike. And, as a former Isle of Man TT winner and World Endurance star, Mat knows how to ride hard, too.

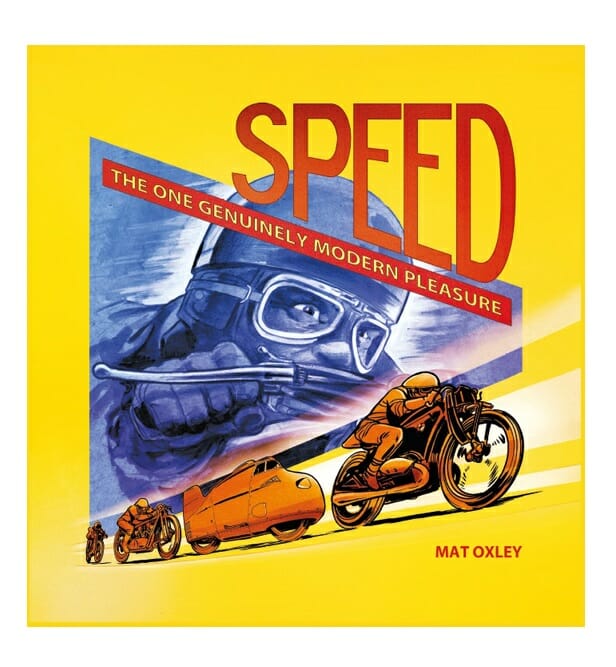

But from there to producing the definitive book on the early days of going fast on two wheels up to a century and more ago, is a look back in time that’s equally authoritative, for that’s what Mat Oxley’s SPEED: The One Genuinely Modern Pleasure indeed is. This highly readable hardback title has 14 chapters full of fascinating, often little-known facts, each of them dealing with a specific episode of man’s obsession with going fast in the early days of motorcycle sport and each reads like a well-worked movie script, complete with directors’ notes for the casting agent.

For each chapter paints a picture of a single remarkable personality around whom the story of his times is recounted. Men like unremittent speed freak T.E.Lawrence (“of Arabia”), who owned a succession of seven Brough Superior SS100 street bikes, each guaranteed by builder George Brough to have been timed at over 100 mph before delivery, a huge speed on narrow, bumpy, 1920s roads. Or BMW’s cool, calculating, multi-Land Speed Record holder Ernst Henne. Henne took his new wife on honeymoon to France so they could lie in the grass beside the Paris-Orleans Route Nationale at Arpajon while he observed his British rival Owen Baldwin at close quarters, in becoming the first man to break the 200 km/h barrier on his Zenith-JAP before tens of thousands of thrill-seeking French spectators who’d paid to enjoy this festival of speed. Later that same year, Henne piloted the supercharged BMW R63 to a new world record of 216.60 km/h (134.60 mph) in Germany, the first of several new such marks this “intelligent, diligent man” would achieve for the German manufacturer, all recounted by Oxley in fascinating detail.

Mat also tells us about French Canadian Jake De Rosier who wore “wind-cheating theatrical tights, canvas running shoes, and a woolly jumper”—crash helmets came later, and were originally optional—to win races galore for Indian in the early teens on the USA’s “Murderdrome” board tracks, but who also finished second to British teammate Oliver Godfrey in the 1911 Isle of Man Senior TT, the first run over today’s 37.73-mile Mountain Course. Figure Jared Mees being narrowly bested by Marc Márquez in the Italian GP at Mugello for a modern equivalent! And there’s Britain’s Joe Wright, the first man to break the 150-mph barrier, doing so in then-remote Southern Ireland aboard his own Zenith-JAP practice steed, because the OEC he was being paid to break the record with had broken its engine. But its owner then displayed the OEC to tens of thousands of visitors to the London Show a month later as the record-breaking bike, all to collect the agreed bonus money! Indeed, the pursuit of the pounds due as bonuses at Britain’s Brooklands banked oval is well described, with riders like Charles Mortimer, father of ’70s GP racer Chaz, owning up to colluding with his fellow denizens of the Brooklands “sheds” to beat the on-track bookies they bet with. The likes of Brooklands regular “Woolly” Worters earned the then equivalent of millions of pounds today in 1929 bonuses from oil, tire, spark plug and other manufacturers, all from carefully planned record breakings. Riders were careful not to break the old record by too much, so that their friendly rivals could earn their own payday a couple of weeks later!

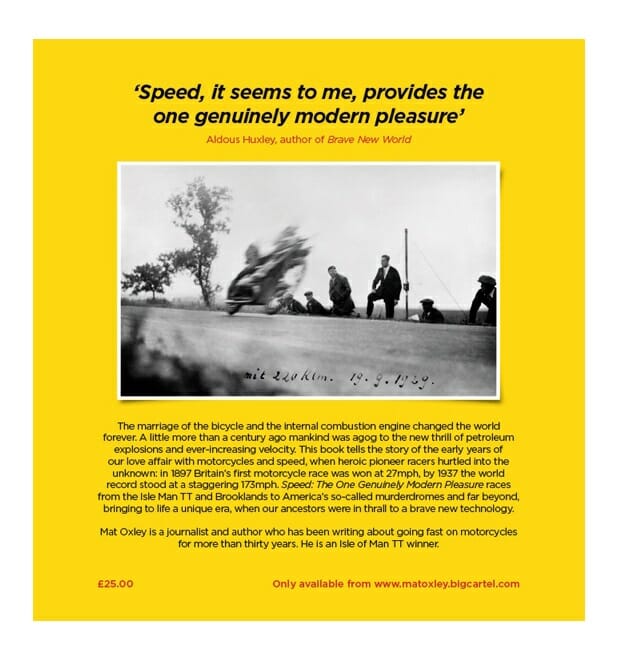

So after recounting how monied aristocrat Charles Jarrott won Britain’s first race for “motor-bicycles” held in 1897 on an oval cycle track in a private park just outside London, following a six-course lunch with “copious bottles of wine,” and in doing so thrilling spectators with speeds as high as 27 mph, Oxley leads us through the next four decades of an increasingly more gripping tale of the pursuit of speed, and how to achieve it. To begin with, going fast in circles on cycle tracks was all that counted, but then with the advent of the murderous city-to-city races in Europe, bikes were expected to stop as well as go, and turn right as well as left, neither of which they did very well, to start with. Even after the advent of the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy, the quest for speed meant straight-line performance above all else, resulting in an all-consuming hunger to break the World Land Speed record. From being primarily a British fetish tussled over by the likes of ex-WW1 fighter pilots, such as Owen Baldwin, sated with the thrill of danger who were looking for a postwar fix, or canny working-class heroes like Bert LeVack, who brewed noxious fuels good for an extra few mph aboard a record-breaker he built from someone else’s cast-offs, the pursuit of speed became an issue of national pride for Germany’s Nazi party. Plus, Italy’s Fascists led by Mussolini, an avid motorcyclist himself.

Mat Oxley tells the story of this battle for supremacy in a truly gripping manner. He puts you right there alongside Italy’s Piero Taruffi as, in 1937, he survives graphically described tank-slappers to become the first rider to officially break the 170-mph barrier aboard the Gilera Rondine streamliner, which invented the across-the-frame format for a four-cylinder motorcycle’s engine. Thanks to Mat’s impressive detailed research into what today is a little-known era so very different from our own, there’s a huge degree of graphic detail in each one of these chapters. Like the unthinkable fact that practice for such events took place in open roads, resulting in the need to pass a donkey-towed cart on a narrow road at over 120 mph, or the revelation that John Alfred Prestwich, creator of the record-setting JAP engines, made his name as a manufacturer of cine cameras. It was a hand-cranked Prestwich 35mm camera that was used to record Captain Scott’s doomed mission to reach the South Pole in 1913. Or how King Leopold of Belgium’s private army ensured untold personal wealth for him—and death for an estimated 10 million native Congolese—in the years leading up to 1908, by cornering the supply in Belgium’s African colony of the only kind of rubber suitable for making John Boyd Dunlop’s newly-developed pneumatic tires. And there’s more—much more.

In an unusual step sure to be appreciated by those readers hooked on learning more about these early days of speed, Mat lists the 58 different books he derived so many of these facts from, and there’s also a fine array of period photos which add immeasurably to the story. Strangely, though, Daytona Beach barely figures in the book, and Glenn H. Curtiss, who essentially invented the V–twin motorcycle before becoming an assiduous record-setter himself, rates only a short mention for his achievement in travelling at 136 mph in 1907 on his self-built V8 motorcycle. But otherwise this book sets Mat Oxley at the very top table of motorcycle historians, and the best compliment I can pay him is that I wish I could say I had written it myself. CN

SPEED: The One Genuinely Modern Pleasure

By Mat Oxley

Price: $48

Pages: 188

Published by Mat Oxley

Click here to read this Book Review in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Click here for more New Products on Cycle News.

Click here for all the latest Road Racing news.