Cycle News Staff | July 12, 2020

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives edition is reprinted from issue #15, April 21, 2004. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. To prevent that from happening, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

Viva Pomeroy!

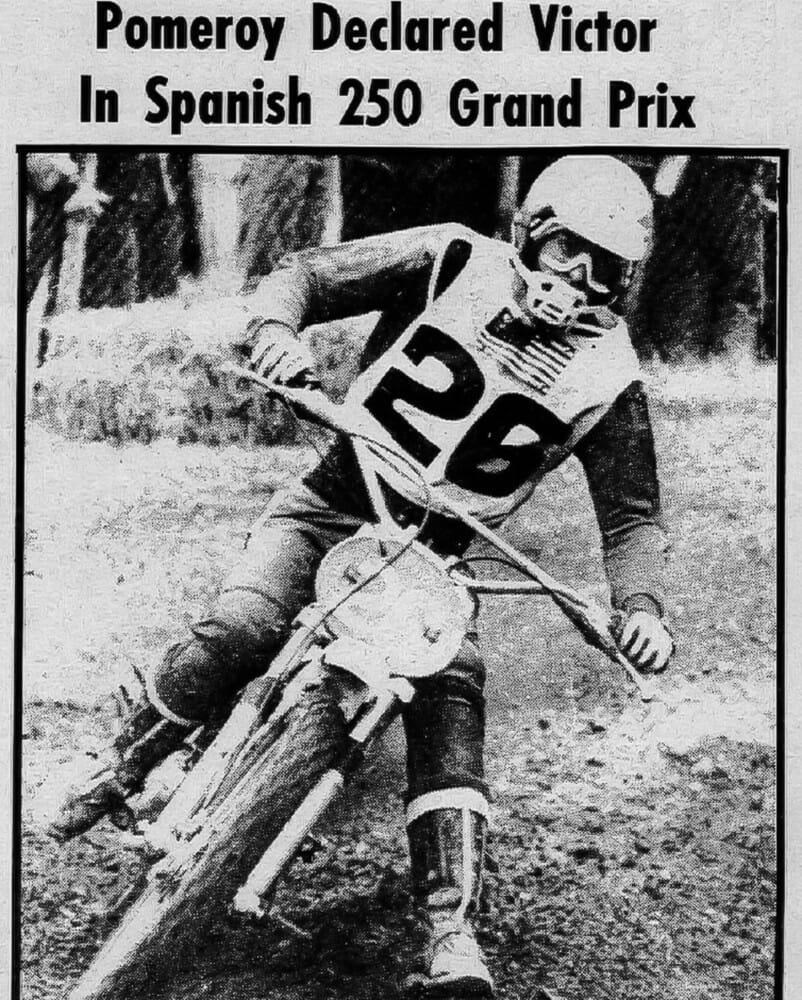

When asked about his historic victory at the opening round of the 1973 250cc World Motocross Championship GP series at Sabadell, Spain, Jim Pomeroy isn’t necessarily proudest of the win itself, nor even the trophy for that win—a trophy that he didn’t even see for 30 years. Rather, he is proudest about what it meant for those who would come after him.

“What I’m proud of is that I gave confidence to everybody on this side of the ocean that yes, we’re capable, and yes, we could win,” Pomeroy, now 51, says. [Pomeroy passed away in 2006 at the age of 53.] “No other American had even been in the top 10 in any GP moto up to that time. I just did what I did because I loved the sport and I loved to ride.”

And if not for the love, Pomeroy might not have made history, because the money certainly wasn’t there in those early days. In fact, he almost didn’t make it to that first GP in Spain.

In 1973, Jim Pomeroy became the first American to win a motocross grand prix, and he did it in Europe.’ The story behind that historic win is legendary, as was the man himself.

In 1973, Jim Pomeroy became the first American to win a motocross grand prix, and he did it in Europe.’ The story behind that historic win is legendary, as was the man himself.

“About a month before that GP, I ran out of money,” Pomeroy recalls. “I was out of my per diem, and the Americans were only getting, like, $50 or $100 for start money because none of us had ever finished in the top 10. Basically, I couldn’t come home early either, because a return ticket would cost me $1000. So, I got desperate and borrowed a 125 and went to a race in Belgium about three weeks before the GP. Andre Malherbe was the champion, riding for Zundapp, and Gilbert de Reuver was number two, and I ended up beating them. So, I go up to the window to get my money after the race, and I’m watching DeCoster and watching Malherbe pick up their $800-$1200 in start money, and I’m thinking, ‘It’s okay, because I’ll get the purse money. They gave me $350. I thought, ‘This isn’t like America at all.’ Then a week before Sabadell, I won a race just outside Barcelona, and I got another $400. Roger got $1500. I wasn’t liking the system at all. And I was homesick.”

If Pomeroy was homesick, then the Sabadell circuit was a welcome sight, as it at least reminded him of home. The fast, hard-clay track was not unlike Saddleback Park in California.

“The narrowest spot was maybe 60 feet wide,” Pomeroy said. “It was so wide that nobody would take outside lines. That was to my advantage, because I didn’t have to deal with traffic then.”

Pomeroy remembers getting off to an 11th- or 12th-place start in the first moto, but he quickly went to the outside, and he began passing one or two riders per corner.

In years past, guys would be a whole gear faster on the outside, but it still wouldn’t be enough to make a pass,” Pomeroy says. “I was going two gears faster on the outside.”

Part of his confidence to charge came from the adrenaline rush brought on by the 150,000-strong partisan Spanish crowd, who cheered the American like a homeboy simply because he was riding a Bultaco Pursang. They didn’t care who was on the Bul’, and they screamed all the louder when he took the lead about three-quarters of a lap into the race. Pomeroy was never headed after that, giving Bultaco a GP win—as a privateer.

“I was a definite privateer,” Pomeroy said. “I had a sponsorship through University Honda/Bultaco of Seattle.

“They bought the bike. It was a stock ’73 Pursang Mk. 6 that I had taken out of the crate three days before and put together myself. The day of the race, I got two free tires from Pirelli. I wasn’t used to getting free stuff, and it took me 45 minutes to change them that morning. I didn’t have a mechanic to help me.”

After winning that first moto, however, Pomeroy suddenly found himself with eight [mechanics], as a swarm of factory Bultaco mechanics jumped in and tore apart the Pursang to freshen it up for the second moto. You’d think that Pomeroy would be pleased to see it, but instead he was pissed.

“When I pulled in, I was surrounded by press and people, and I didn’t know what happened to my bike,” Pomeroy remembers. “It was running so perfectly that I didn’t want anything touched. Then finally, the crowd started going to other people, and I looked and saw my bike had all these mechanics on it, and they had torn it apart. I couldn’t believe it, and I ran over and said, ‘What are you doing?!’ But it was too late. They had already torn the clutch apart and put new plates in it. Then in the second moto, the clutch slipped so badly off the line that I got a really bad start.”

Pomeroy once again worked the outside to perfection. Using his momentum to baby the clutch, he passed his way up to third place by the 30-minute mark. But then came disaster, as he crashed in a fourth-gear corner. Fortunately, Pomeroy was able to regroup and get going again.

“I got back up and caught back up to Hans Maisch to get fourth place, which gave me the overall win.”

Or did it? When the awards were handed out on the podium, Maisch was given the GP trophy, and Pomeroy was relegated to second place. It turned out to be a mistake of monumental proportions.

“What happened was that in years before you had to finish both motos to get GP points, but they changed the system for 1973 to points by moto, and that’s where the officials got confused and gave my trophy away. I went up to the podium and they put me in second place.

“I wasn’t too happy about that.”

By the time the officials realized the mistake and corrected it, Maisch had made off with the trophy, and, when told of the change, the German refused to relinquish it.

“I asked him for it three or four times, and then I just gave up on it,” Pomeroy says. “So I went without it, but it didn’t matter, because I won half a dozen more GPs after that, and a lot more motos. And after that race, I started picking up $1200 in start money, and then I started liking the system. It took that GP win to get it going.”

He would continue riding Bultacos through the 1976 season before coming home to race AMA nationals for Honda in ’77 and ’78. He then returned to Europe for Bultaco in ’78 and rode until the factory closed its doors before switching to an ill-fated ride on the Italian Beta brand in 1980. Upon returning to America in 1981, Pomeroy was more or less forced into retirement by a bizarre AMA rule that labeled him as a non-qualified rider for AMA nationals even though he had held an FIM license.

But that wasn’t the end of Pomeroy’s racing days. Based in Washington, he remained active in the AHRMA vintage motocross scene while taking care of his real-estate concerns. In fact, it was just last year, at an AHRMA National MX event in Chehalis, Washington, that Pomeroy got the surprise of his life, as he was awarded his first-place 1973 Spanish GP trophy.

“I couldn’t believe it when that happened,” Pomeroy says. “My brother [Ron Pomeroy] and a couple other people put it together. I never dreamed I’d get that back. It choked me up pretty good.”

Trophy or no trophy, Jim Pomeroy was the first American ever to win an FIM motocross grand prix. They never gave out a trophy for that accomplishment, but it’s also something that they’ll never be able to take away. CN