Cycle News Staff | May 17, 2020

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives edition is reprinted from April 2004. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. To prevent that from happening, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

The Beginning: The Superbowl of Motocross

By Scott Rousseau

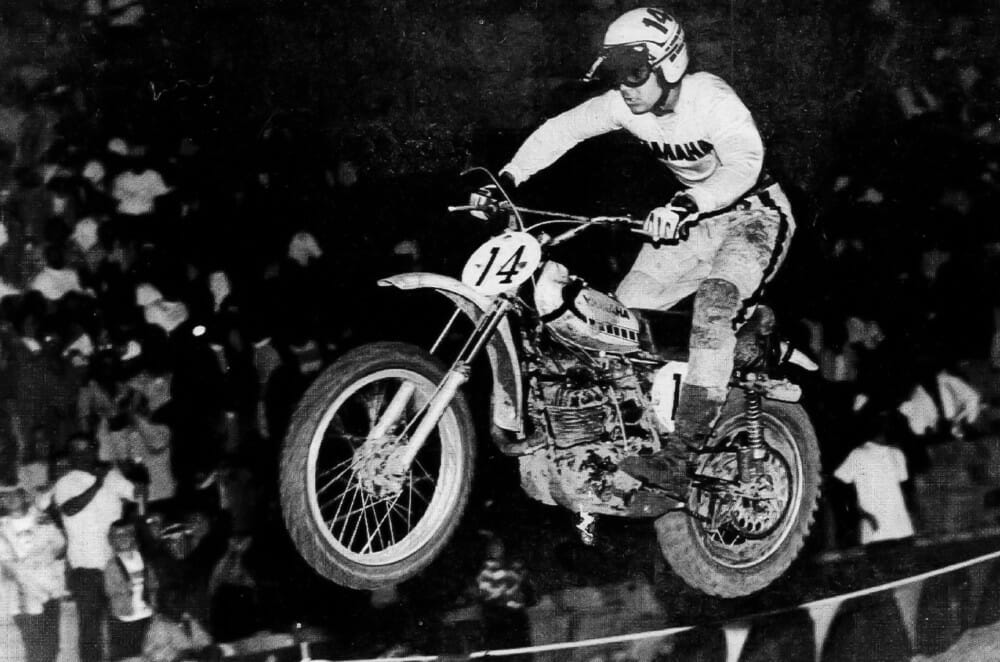

Dunn’s Law reads that “Careful planning is no substitute for dumb luck.” Nobody is sure when Dunn first wrote that little pearl of wisdom down for the first time, but it might well have been from the cheap seats in the Los Angeles Coliseum on July 9, 1972. For that was the date in motorcycling history that gave birth to the phenomenon known as supercross. And, true to its emerging form, the first one, named the Superbowl of Motocross, was highlighted by the heroic performance of a young Californian named Marty Tripes.

“I had just turned 16 on June 29,” Tripes, already a factory Yamaha rider by then, recalls. “It was a completely new thing. I had just started riding the Inter-Ams because I had turned the legal age, 16, before the Washington race. So, we went down to LA. Everyone was calling it the ‘Stupid Bowl.’ They didn’t think it was going to be cool. Nobody thought that it was going to fly. Nobody knew what to expect. I knew the promoter, Mike Goodwin, and he was definitely a kook. He showed up in a Rolls Royce with either a lavender or a pink suit on (laughs). He was definitely trying to do the rock & roll thing with supercross. Everyone thought that he was nuts.”

Tripes says that a lot of riders complained about the layout of the track. “But more I looked at it, the more I liked it,” Tripes says. “It was tight, fast, and it required a lot of control over the bike. The more the other riders looked at it and thought that it was crazy, the more I thought, ‘You know, this is going to be fun.’ The concept was great, and I think that a lot of riders weren’t looking at it like that. They were looking at it like, ‘Do we really have to ride this?’ The track was nothing like an outdoor track. The creation of doubles and triples, everything started from there, and that was all new to us. I think they even had a big mud puddle there, if I remember right.”

Tripes says that there were about 15,000 or 20,000 people on hand, but Cycle News’ coverage of the event listed closer to 35,000 in attendance.

“To look at it from the inside, it didn’t look like very many, but it was a lot,” Tripes says. “The Inter-Ams, we were probably pulling 10,000, maybe 15,000 if we were lucky.”

“I think that it was three 20-minute motos, a lot of laps,” Tripes remembers. “I think we made 25, 30 laps per moto. They were long races. On a track that tight, putting out that kind of effort under those conditions was completely different for us.”

Putting out maximum effort was something that the invading Europeans were used to, however, and the factory Husqvarna team was represented by some of the best, including its number-one rider Torlief Hansen. Also on hand for Husky were Arne Kring and Torsten Hallman, while Yamaha had the equally tough Hakan Andersson. Of these, Hansen drew first blood by winning the opening moto, with Tripes second.

“Some of the guys who didn’t do so well really bitched out about it [the track], but I just liked it more,” Tripes says. “They [the Swedes] were tough business, but I was so young that I didn’t really care. I remember my dad saying that I only needed to worry about beating one of the Czech riders, and that’s what I just focused on.”

American John DeSoto and his factory Kawasaki took the early lead in the second moto, but it wasn’t long before Kring was pressuring him, and the Swede soon took over the lead. Tripes worked his way from a bad start to run second at the finish. The published account is that while he didn’t look all that fast, Tripes was smooth as silk.

Then came the final of the three motos. Hansen and Tripes were tied for the overall lead, but it was Andersson’s turn to shine, as he got the holeshot ahead of Hansen and Kring. It appeared to be all over for Tripes who was mired back in 10th place. Then Tripes began to get the crowd charged up as he managed to pick off a rider per lap, making seemingly impossible passes to make his way to third place, behind the smooth-motoring Hansen. Slowly but surely, Tripes closed the gap on Hansen. The crowd went wild as the kid blew off the main Swede, passing him for second place and pulling away to secure the overall Superbowl of Motocross win via a trio of runner-up finishes.

“That was the biggest win of my career to that point,” Tripes says. “That race put me on the map. I was so young. Everyone thinks that Bubba Stewart beat my record [youngest rider ever to win a supercross], but he was actually off by a few months. And what he did was win a 125 supercross. I won a 250 race against the world’s best. Not to take anything away from Bubba, but I think I accomplished a little bit more.”

That said, Tripes cites Stewart as one of few riders on the scene today with the heart and killer instinct that Tripes says most of the top riders had back in his day.

“I don’t even go to the races anymore,” says Tripes, now 47 and living in Fort Wayne, Indiana. “The riders today make me so mad because most of them don’t care. They don’t race. There’s maybe three guys, and the rest of them are just there, wondering how they look in their uniforms. Bubba Stewart is like that and more. He wants to win, and you can see it. Back when I raced, you had at least seven guys fighting it out for first place. Now, these guys get paid so much, they think that it’s okay to get third. To us, the money didn’t mean as much as winning the race.”

Having retired from active competition at the end of 1981 [he attempted a one-time comeback at the Rose Bowl in 1984], Tripes has spent the last 20 years of his life in the paintball game industry. He is currently developing ammunition for Tippmann Pneumatics, one of the industry leaders.

“I love it,” Tripes says. “I have been doing it for a long time now.”

Even though he has been away, Tripes says he has a lot of fond memories of his racing days, several of them from that 1972 Superbowl event that spawned an entirely new and exciting form of motocross. If there is a single memory that stands out, though, it was the return to the Superbowl in 1973.

“That second year, when I switched from Yamaha to Honda, when we went back, the place was packed,” he recalls. “They had like 52,000 or 53, 000 people there in ’73. That was big. From the riders’ point of view, we were in awe. All those people, and they’re here to watch us. That’s when we knew.”CN