Cycle News Staff | April 26, 2020

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

This Cycle News Archives edition is reprinted from September 2004. CN has hundreds of past Archives columns in our files, too many destined to be archives themselves. To prevent that from happening, we will be revisiting past Archives articles while still planning to keep fresh ones coming down the road -Editor.

The Original Bubba

By Scott Rousseau

After finishing fourth in the 1983 AMA Grand National Championship Series, a Texan by the name of Don “Bubba” Shobert wanted a factory Harley-Davidson dirt track ride in the worst way, but the company was already fielding a top-notch, three-rider squad.

Honda, however, was looking to make a run for the title, and it needed good riders. Shobert was one of two men fit for the gig.

“For ’84, Harley had Springer [Jay Springsteen], [Randy] Goss and [Scott] Parker, and me and Ricky Graham were like the next two guys in line,” Shobert says. “had a pretty full boat already. There was nowhere else for me to go.”

It was hardly a second-class option, as Honda’s once-laughed-at dirt track program had begun to turn around. Following Scott Pearson’s win at Louisville on the Honda NS750—an odd machine with an engine based on the company’s CX500 street bike—Honda introduced its RS750, a “full-race” motor that would prove itself in competition over the next four seasons.

“It looked like it was working good enough that I could ride it, and it would be worth it for the money,” Shobert recalls.

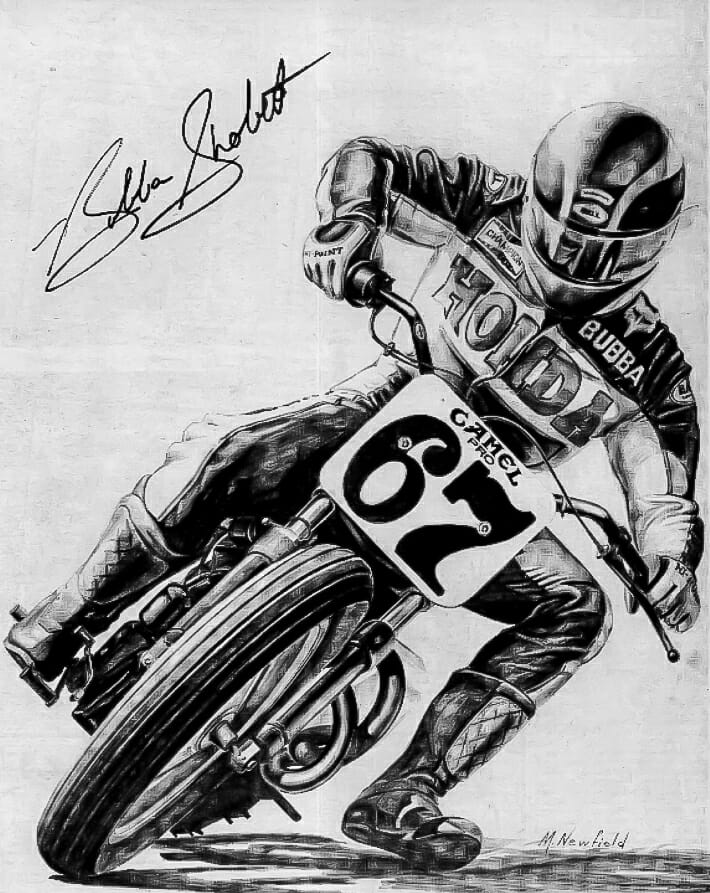

Bubba Shobert won his first flat track title in 1986. The Texan went on to win two more.

Bubba Shobert won his first flat track title in 1986. The Texan went on to win two more.

Shobert was assigned to tuner Skip Eaken. Immediately, the two were successful. If it weren’t for his listening to some bad advice at the St. Louis Short Track, which led to an altercation with fellow Texan Terry Poovey and a subsequent nine-race suspension for Shobert, he might have won the title in his first season with Honda.

“Poovey wasn’t with the Honda deal anymore, and he was kind of mad because we were doing good,” Shobert recalls. “I had raced against him a lot growing up, and he was always older than me. I took a lot of him stuffing me along the way. In St. Louis, it happened in practice. We were going down the straightaway, and he put me into the hay bales that were lining the track. I hit one and endoed.

“Graham was my teammate, and he was in the pits, and he said, ‘Man, if he’d done that to me, I would punch him!’ ”

Shobert did, got busted by the AMA, and effectively “boxed” himself out of title contention. Years later, Graham would admit that his suggestion was more calculated than emotional, though Shobert isn’t as angry about that as he is about how the AMA handled the affair.

“I fell for it,” Shobert says, “but what gets me is that they suspended me for nine races, and I got to race at St. Louis and one more race, which I won, while I was under appeal. Then when they ruled against me, the AMA took my points away from those two races and counted them as two of the nine. Yet when Bill Werner got caught cheating—he grabbed the wrong cylinder off the shelf, you know that deal—King got suspended for four races, but he got to keep the points he earned while he was under appeal. What did I ever do to them [AMA]?”

The aftermath of the Shobert suspension was probably the most dramatic finish in AMA Grand National Series history. Shobert lost the ’84 title to Graham by one point at the Springfield Mile. Even so, the magic was just beginning for Shobert and Honda, who went on to be the toughest trio in a field as talent-rich as at any time in the sport’s history, with Shobert reeling off three consecutive titles in 1985, ’86 and ’87.

Then and now, there are those who would argue that it was Shobert’s motorcycle—backed by Honda’s might—which was doing all the winning. Shobert scoffs at that notion.

“I think it was the combination of the way me and Skip and [engine-builder] Ray Plumb worked together,” Shobert says. “We worked really good together. Except for one time, I don’t remember ever winning any of the miles that I won by a large margin, and I definitely wasn’t the fastest qualifier every week,” Shobert says. “What’d they think, that I just wasn’t trying?”

Yet it seemed that every time the AMA rules were amended, they seemed to favor the Harleys and hurt the Hondas—or so the legend goes. Shobert doesn’t really recall that, nor does he recall the oft-fabled hatred by dirt-track fans toward the Japanese in the uniquely American sport of dirt track.

“I feel like I was treated good … equally,” Shobert says. “I didn’t never see that [negativity] personally, but I was so focused on my racing that I didn’t see a lot of things that I see now.”

Animosity or no animosity, Shobert’s time at the top was finite. He and Honda lost the number-one plate to Parker and Harley-Davidson in 1988. The defeat cost him a shot at a true milestone. If he had won, he would have joined the great Carroll Resweber as a rider who won four consecutive titles.

“Records like that never really did cross my mind when I was out there,” Shobert says.“I guess the main record that I’m proud of is winning the five different types of racing [grand slam]—Dick Mann, Kenny [Roberts] and me. Doug [Chandler] actually did it after it [road racing and dirt track] was separated, and it was a Superbike class—not to take anything away from him, because he deserves it.”

For Shobert, being recognized for what he had done was never as important as what he was going to do next, and while he isn’t exactly thrilled to have lost to Parker—this after Shobert was disqualified for winning the Syracuse Mile on a motorcycle that was half a pound too light—both he and Honda were already moving on anyway. It was announced that neither would be back for the 1989 dirt-track season.

“For me, it wasn’t so much that Honda said they weren’t going to do it anymore as much as I didn’t want to do it anymore,” Shobert says. “I won the Superbike championship in ’88, and my next step was going to be the GPs.”

Unlike his long and storied dirt-track career, Shobert’s GP career was not as long—though it was no less storied. At Laguna Seca, in Monterey, California, Shobert’s career came to a crashing end just three races into the ’89 season when he ran into the back of Australian racer Kevin Magee, who was parked on the track, showboating for the crowd by doing a burnout—a typical postrace celebration. Shobert suffered massive head trauma in the horrific incident, which was captured on national television. He would eventually recover, though he would never race again.

Today [in 2004], at age 42, Shobert says he has no regrets about his career or his decision not to attempt a comeback.

“I would have if I could have,” Shobert says, “but I knew that I wouldn’t be near as good as I was even if no one else did. It’s like you climb that ladder to the top, and it’s hard to start at the bottom again. Even today [2004], a lot of people say, ‘Why don’t you race dirt track and help us out?’ I can’t do that. In the ’80s, Bubba Shobert was the only thing I lived for. The only thing that I thought of was myself, but having kids changes that.

“Plus, I guess a guy likes to think that he’s as good as he was.”

Bubba Shobert is as good as he was. Anyone who knows him will tell you that. CN