| April 13, 2020

By Jim Scaysbrook

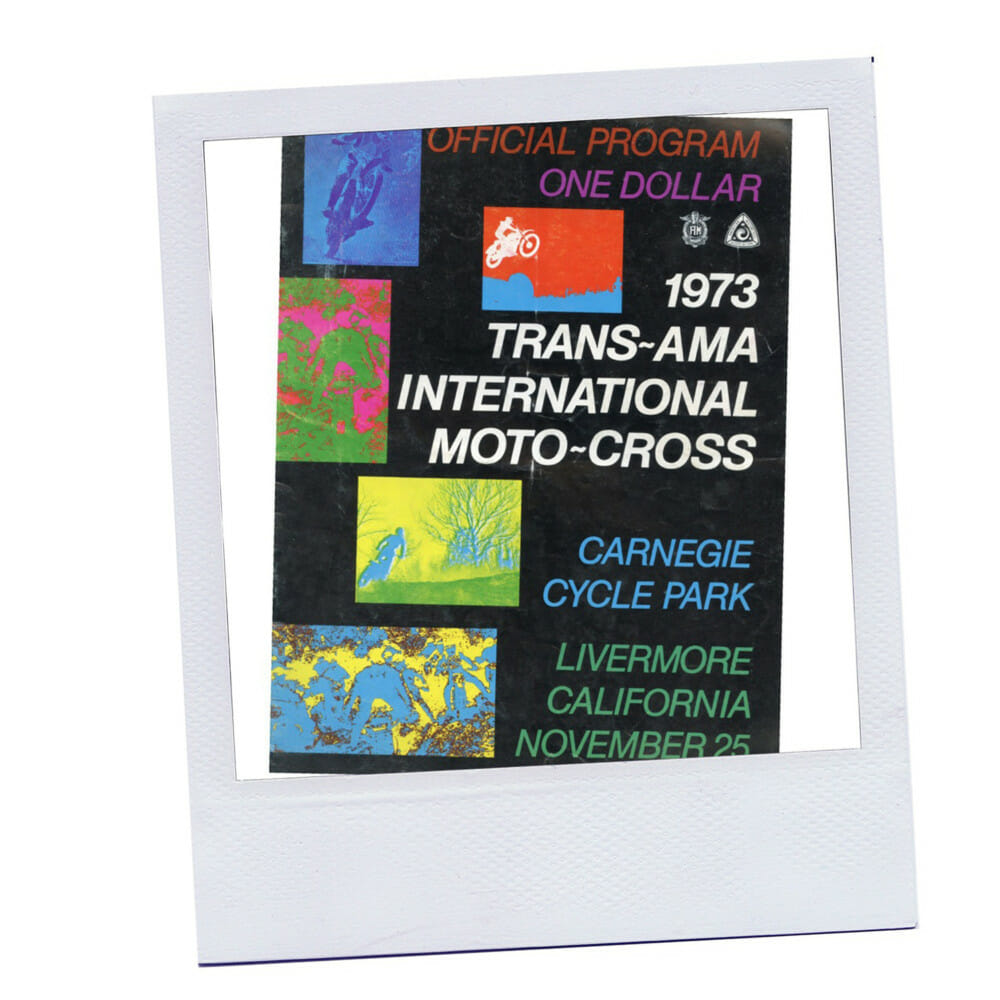

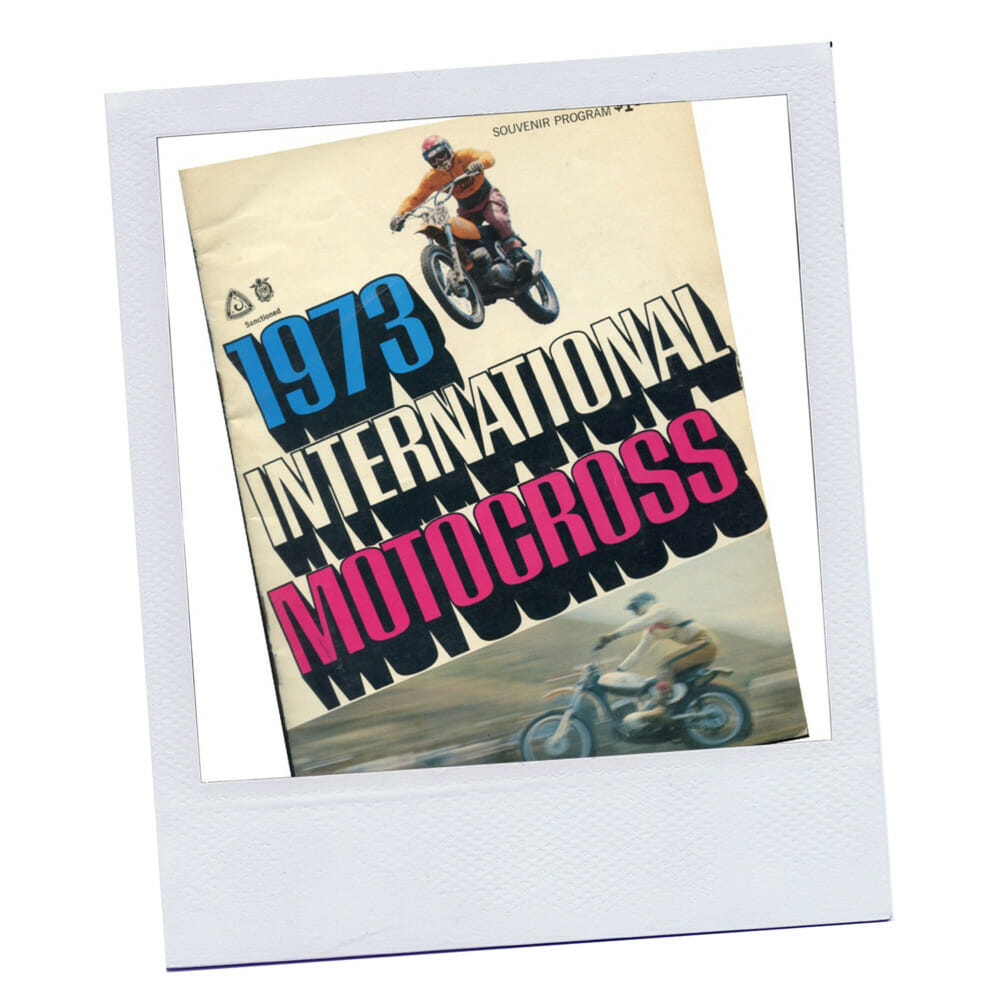

1973 Trans AMA Motocross | Tenderfoots On The Trans-AMA Trail

When a couple of raw Aussies made the foolhardy decision to mix it with the world’s best motocross riders in 1973.

Jimmy Weinert leads Aberg, Bauer and Weil in Georgia

Jimmy Weinert leads Aberg, Bauer and Weil in Georgia

By Jim Scaysbrook | Photography Old Bike Australasia

To my left, the works Maico guys were going through the usual posturing on the grid—the tall Dutchman Gerrit Wolsink, inscrutable German Adolf Weil, and the intensely focussed Willy Bauer. The bikes looked trick. Compared to my stock 400 Maico, a Lambretta Tourista looked trick.

On my right, a sea of yellow. Works Suzukis for Sylvain Geboers, Roger DeCoster and Americans Rich Thorwaldson and Mike Runyard, Pierre Karsmakers’ “Cantilever” Yamaha, Kawasakis for Jimmy Weinert and Brad Lackey, Bengt Aberg’s factory Husqvarna, Jim Pomeroy’s works Bultaco—a grid of 40—including two unknown Australians.

We noted the prize money stretched down to 20th place, so a top 20 shouldn’t be that difficult, should it?

Roger DeCoster roosts the factory Suzuki Canada.

Roger DeCoster roosts the factory Suzuki Canada.

What the hell am I doing here?

I should have been concentrating on the starting gate, or the newly graded track that stretched out beyond—a carpet that would shortly become a mass of ruts and bits of bikes. But an idée fixe dominated my mind, a single thought, “What the hell am I doing here?”

It was a fair question, which had its genesis in a spot of daydreaming nearly a year before. Back in Australia, a fellow by the name of Linden Prowse decided to off-load his successful pet food business and dabble in other things, like motocross promotion. It wasn’t his first choice. He really wanted to hold a big chess match, and announced a AUD $225,000 bid for the right to stage a World Chess Championship match in Sydney, between American Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky of the then Soviet Union. He didn’t get the gig, which was awarded to a rival bid to stage the series of 24 matches in Reykjavik, Iceland, where it was dubbed “Match of the Century.”

So, flush with cash from the disposal of his recycled animal enterprise, Mr. Prowse hit upon the idea of an international motocross series in Australia for what he termed Moto Crosse [sic]. A six-strong troupe was signed up: DeCoster, Joel Robert (who between them boasted no fewer than 11 world titles), works Husqvarna rider Bengt Aberg, winner of the 1969 and 1970 FIM Motocross World 500cc Championships, Welsh rider Andy Roberton, also contracted to Husqvarna, plus the works Maico pairing of Germans Adolf Weil and Willy Bauer. Needless to say, the “internationals” ran riot, winning every race of the three-round series, which was condensed into three meetings in just eight days across three Australian states. With a Honda dealership to look after, I managed to compete in only the Sydney round, while my mate Laurie Alderton, 10 years my senior, did two.

Later, when the Europeans had departed with the prize money, Laurie and I got to thinking that a bit more of this would be a good thing. Europe was out of the question, but the emerging U.S. motocross scene might just be possible. Originally, we thought of entering the International Six Days Trial, which in 1973 took place in Massachusetts, but the red tape associated with that quickly quashed the idea.

Instead, I wrote to Art Barda, at the time general secretary of the AMA, enquiring sheepishly about the possibility of Laurie and I getting into the Trans-AMA series, which kicked off at the end of the 1973 European season. To my great surprise, he actually replied, and in a very positive fashion. It was time to piss or get off the pot, so after a bit of soul searching and asset sales to finance the venture, we shook hands on the deal. With a partner, I imported products from Filtron (coffee goods), based in Van Nuys, California, and they were quite happy for us to ship our bikes there—my 400 Maico and Laurie’s 400 CZ.

It looks like a paddock but there’s a track there somewhere. Willy Bauer dodges track invaders in Canada.

It looks like a paddock but there’s a track there somewhere. Willy Bauer dodges track invaders in Canada.

Time to get on with it

In early September, we arrived in Los Angeles on a Saturday, grabbing a piece of carpet for a couple of nights in a minuscule apartment rented by Ken Stubbe, an American who had raced in Sydney for a while, his wife and one-month-old baby girl.

It was very cozy.

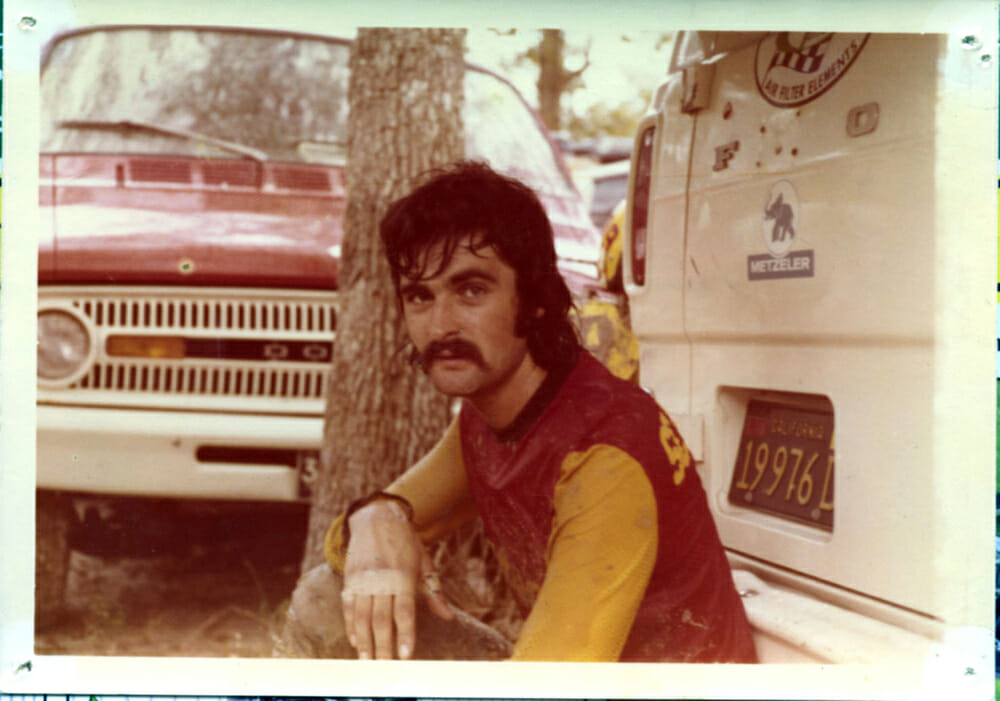

Come Monday, we were at Filtron, and, miracle of miracles, the bikes were there, ready for us to collect. Except we had nothing to collect them in or with. Soon after we found ourselves trawling the used car lots on Hawthorne Boulevard. I left the decision to Laurie, a trained mechanic who could fix anything. He was so adept at solving mechanical problems the Americas on the MX series nicknamed him “The human Swiss Army Knife.”

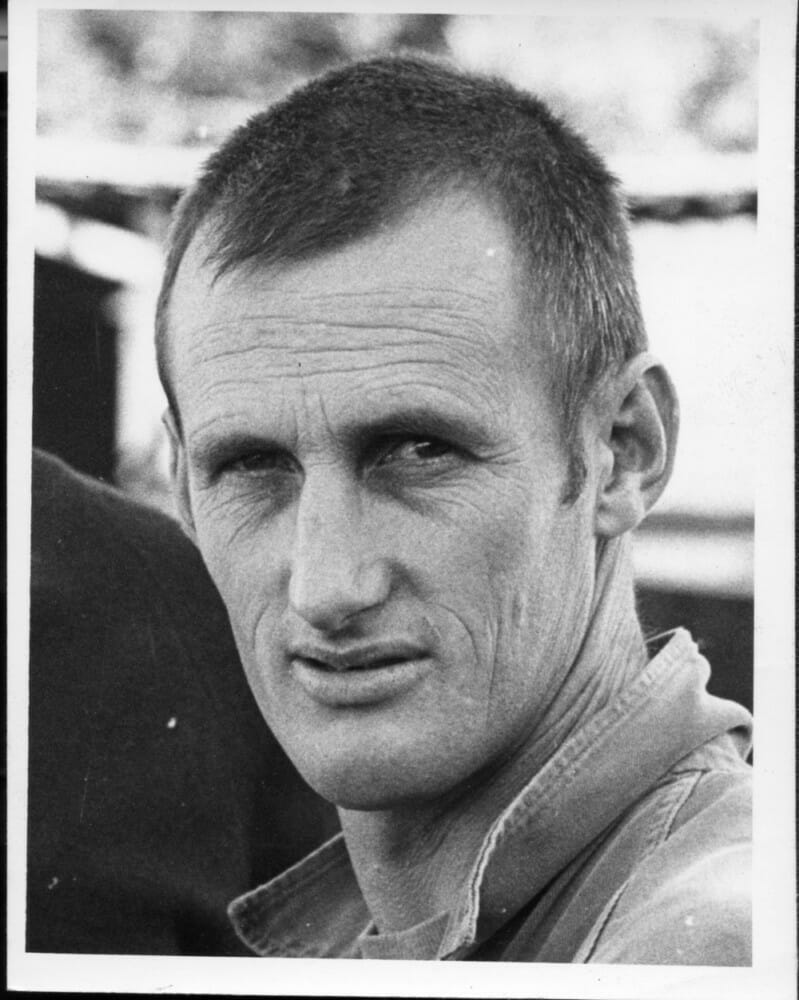

Laurie Alderton, “The human Swiss Army Knife.”

Laurie Alderton, “The human Swiss Army Knife.”

Our new set of wheels was a long wheelbase V8 Ford van, longer than anything I had ever seen, but quite normal, I was assured. It started and ran okay, and the paint was shiny, so I figured that’s all that mattered. Wrong.

One day later we were loaded up and heading east on Route 66—the first meeting of the series was at Zoar Moto Park Springville, New York, on September 23.

Our Ford van at Niagara Falls prior to the New York round.

Our Ford van at Niagara Falls prior to the New York round.

Along the way across the country, the weather got gradually colder, and so did the oil in the sump. Each morning, the big white van got progressively harder to start until one morning, it plumb refused altogether. Laurie stood staring at it for a minute or two, scratching his chin, until he drawled, “I reckon the timing chain is worn out and is jumping the sprockets when the oil is cold, ‘cause there’s no adjustment left on the distributor.”

I nodded blankly.

With that, Laurie pulled out his overalls from his toolbox and dismantled the entire front end of the van, including the timing chest of the engine. He then wrote out a list of parts we needed and pointed me in the direction of the nearest Ford dealer. This was my vital role in the process of getting us back on the road. By the next day, the whole thing was back together and ran perfectly thereafter.

Philadelphia Stadium, round two. My first (and last) indoor event.

Philadelphia Stadium, round two. My first (and last) indoor event.

Up against the world’s best

So here we were at Zoar Moto Park, and our initial thoughts of a top-20 finish and some cash to get us to the next round now seemed pure fantasy. In the first practice session, I reckoned I needed a map to find my way around the course, which was brand new. It plunged up and down the sides of a valley and seemed to go on forever. On one downhill section, DeCoster leapt clear over my head, gracefully dropping onto the valley floor and scooting up the other side, disappearing in a trice. This was going to be an interesting race. It was, and the closest we came to the top 20 was when they lapped us, which they did at least twice. We did finish though, classified around 25th and 26th, with two or three other also-rans astern of us.

The level of competition was simply beyond our comprehension. Weil was a tough guy. Unlike everyone else, he wore a Bell open-face helmet with no face or mouthguard—I think he just caught the rocks in his teeth and spat them out. At 34, he was a veteran, but as tough as teak and super-fit. After each “moto,” the Maico mechanics swooped on the three works bikes and stripped them, tossing chains, sprockets, cables and even handlebars into a rubbish bin. As soon as they weren’t looking, I swooped on the bin and recovered everything.

Jim Scaysbrook at Mid-Ohio. Two DNFs and a sore butt.

Jim Scaysbrook at Mid-Ohio. Two DNFs and a sore butt.

If Zoar was an eye-opener, what followed was science fiction. In a giant stadium in Philadelphia, an indoor motocross track had been created. Whoever was in charge of the earthworks was clearly a sinister and sadistic individual with no regard for human life or delicate machinery.

By today’s standards it was probably tame, but 47 years ago it was horrific.

The jumps were massive mounds with sheer drop-offs, no such thing as a landing ramp. In practice, I totally demolished both wheels, but just when I was contemplating spectating for the evening, a cigar-chomping fellow approached me. He had a big motorhome in the spectator car park and hitched to the rear was a 400 Maico. “Just take what you need,” he beamed, slapped me on the back and disappeared to the bar. I took both wheels and the chain. The replacement front lasted half of the first race and was rebuilt in the interim from the best bits of both, while the rear suffered a similar fate in the second leg. The entire front end of Lackey’s Kawasaki departed from the chassis, and he carried the wreckage across the line to claim points as there were so few finishers.

Knackered but happy; Scaysbrook after the second race in Texas, and his first prize money of the series.

Knackered but happy; Scaysbrook after the second race in Texas, and his first prize money of the series.

Burning the midnight oil

There were only a few days to get to the next round in Copetown, near Hamilton in Canada, so while I drove, Laurie sat in the back of the van, building wheels from bits we had scrounged. I liked the track. It was grassy and fast with rolling hills and no murderous, fiendish jumps. In the first leg, I finished 20th; things were looking up. Flushed with confidence, I burst from the starting gate in Leg 2, grabbed second gear and the gearbox exploded. Laurie soldiered on for another placing in the mid 20s.

Here began an interesting sequence of events.

Round four was at Mid-Ohio, and we had been invited (or invited ourselves, possibly) to use the facilities of the Maico dealer in Piqua, Ohio. Driving non-stop from Canada, we arrived late at night and headed for the dealership, which was naturally closed. No matter, there was a large empty car park beside the shop, so we crawled into our sleeping bags in the back of the van and passed out. Around midnight, the doors to the van were flung open and an intense white light flooded the interior. Through the glaze I could make out what appeared to be rifle barrels. A cacophony of aggressive voices demanded we get out and put our hands up, which we did as quickly as possible. Frisked and searched, the police soon decided we were not felons, arsonists or masters of crime after all, and delivered a lecture that we were lucky not to be charged with loitering, trespassing, and speaking with a funny accent. They also said we could not remain where we were, so after they holstered their weapons and departed, we drove around for a while before taking up residence somewhere less visible. The owner of the shop, which was called Honda of Piqua, was a great guy and gave me the parts I needed to rebuild the gearbox, which was just about all of it.

Series winner Adolf Weil grabs the holeshot at Road Atlanta ahead of Gary Semics (44)

Series winner Adolf Weil grabs the holeshot at Road Atlanta ahead of Gary Semics (44)

Ohio was another track that I liked, set inside the road-racing circuit over undulating countryside. A placing just inside the top 20 looked like a possibility until a single 8mm nut fell off. Unfortunately, this was the nut that held the seat in place. The wayward seat was retrieved by a spectator, who held it up for me to see as I pressed on, seat-less, to be classified 29th, standing up as much as possible but with my backside copping a fearful beating from the exposed top frame rails. The errant nut was liberally doused in Loctite, and safety wired as well, ready for leg two, but despite fitting a chain from my stock of ex-works team parts, it broke on the very last lap. Still no cash in the kitty.

Scaysbrook at Mid-Ohio before the seat fell off.

Scaysbrook at Mid-Ohio before the seat fell off.

Soldiering on in the face of adversity

Washington, Indiana was next, a very wet meeting at Snyder MX Park that brought nothing but frustration for us with bikes that were approaching the worn-out stage. At least we both finished each leg, in mid-20th positions. This was the year of the long-travel rear suspension revolution, and at every meeting, the works bikes sported some new, super-trick setup. The Yamahas, of course, had the Belgian Tilkens monoshock system, but the Maicos, Huskys, and Suzukis all appeared with various versions of the shocks moved up the swingarm closer to the pivot. Here we met an American who had bought the works Maico that Ake Johnson had used to win the 1972 Trans-AMA series. It was still as he had raced it, and someone said to this fellow, “When ya gunna move the shocks up on that thing?” His reply was priceless: “When I can ride it as fast as Ake Johnson did last year.”

On to Atlanta, Georgia, with an interesting track of red clay laid out inside the Road Atlanta road-racing track. I wasn’t feeling too good, and after a few laps of practice I decided to sit it out, grab my camera and take a few happy snaps of the action. Laurie’s stock 400 CZ was now getting pretty tired, so he grabbed my Maico for the day and finished both races in a commendable but still cashless position.

Orlando, Florida was next—a lap completely composed of deep black sand—and no one saw which way Adolph Weil went. I certainly didn’t; by the end of each leg, the sand whoops were so deep I was feeling seasick.

Laurie Alderton on Scaysbrook’s Maico at Road Atlanta.

Laurie Alderton on Scaysbrook’s Maico at Road Atlanta.

After spending a few days lolling around on Cocoa Beach, it was time to hit the road for Rio Bravo Park near Houston, Texas, and it rained most of the way across from Florida. It was still raining as the meeting began, and it never stopped. In the first leg, the chain dropped off twice due to the sprocket being buckled after swallowing a length of fence wire, but I still finished, drenched, covered in thick red mud and exhausted.

The Maico covered in Texas mud.

The Maico covered in Texas mud.

But leg two brought joy.

After nearly one hour of racing, I finished 15th, giving me 20th overall and $200 in prize money. Hallelujah! The race marked the first-ever American victory in the Trans-AMA, with Weinert taking the checkered flag.

It turned out to be my final ride in the series. Back home, in addition to the Honda dealership, I had a modest sideline importing motorcycle accessories, but the quality motocross stuff that was commonplace in the USA was still not available, so I decided to abandon the Trans-AMA and fly to Italy for the big annual EICMA Show in Milan, where all the accessory manufacturers would trot out their latest wares.

Jim’s Maico in the pits at Mid-Ohio. A factory racer, this is not.

Jim’s Maico in the pits at Mid-Ohio. A factory racer, this is not.

It was a worthwhile move as I snared the Australian distributorship for Sidi boots and held it for quite a few years. Meanwhile, I left the Maico and the van with Laurie, who completed the series, and even finished in the money once in the final four rounds—not bad for the oldest rider in the field—before selling the van in LA, crating the bikes for shipment back to Sydney, and flying home.

It had been quite an experience, humiliating on occasions, but there’s no doubt we were both far better riders as a result. But motocross was now a technology war, with suspension systems so sophisticated that you could jump over tall buildings, and tracks built to suit. It really didn’t grab me, and I switched to road racing, although Laurie continued motocross for years before branching into enduro and representing Australia in several International Six-Day Enduros. CN