Alan Cathcart | March 28, 2020

Riding The Roberts Family World Title 500s | Like Father, Like Son.

There has only been one father and son who have each won the 500cc World Championship, our own Kenny Roberts and Kenny Roberts Jr. Come for a trip down memory lane as we ride the bikes they made famous.

Photography by Henny Stern and Paul Barshon

Exactly 40 years ago this year, Kenny Roberts Sr. defeated the theoretically more powerful rotary-valve Suzukis to win the third of his hat-trick of 500cc GP World Championship titles aboard the factory piston-port Yamaha YZR500 OW48R. Coincidentally, exactly two decades later, his son Kenny Roberts Jr. became King Kenny in his own right, by following in dad’s tire tracks and beating the then much more potent Yamahas and Hondas to win the 2000 500cc GP title on his Suzuki RGV500. In doing so, he achieved a unique double victory—the first time ever that a father and son had won 500cc GP world titles on two wheels, exactly 20 years apart.

I’ve been rather lucky in my career in that I have tested many a great rider’s machine, but to ride the Kenny Sr.’s Yamaha and Kenny Jr’s Suzuki on separate occasions was indeed special.

Let’s take a trip down the Roberts family memory lane, starting off with Kenny Roberts Sr.’s 1980 Yamaha YZR OW48R.

Is there a Yamaha more legendary than that of King Kenny? This is the steed from his final championship year of 1980.

Is there a Yamaha more legendary than that of King Kenny? This is the steed from his final championship year of 1980.

Kenny Roberts 1980 Yamaha YZR500 OW48R

Vital Ingredient

The chance to test the actual reverse-cylinder OW48R Yamaha which Roberts Sr. rode to win the last of his trifecta of 500cc world titles came at Assen, the circuit at which this piece of lateral thinking hardware made its debut back in June 1980. Thanks to the enthusiasm and commitment of British collector Chris Wilson, and the inspired restoration skills of former factory race mechanic Nigel Everett, the yellow and black Roberts Yamaha represents yet another vital ingredient of the early days of 500 GP two-stroke history saved from the scrapheap and returned to the racetrack as part of the Wilson collection.

The Yamaha’s Monocross rear suspension was a marked improvement over the twin shocks used by the Suzuki.

The Yamaha’s Monocross rear suspension was a marked improvement over the twin shocks used by the Suzuki.

40 Years On

“The OW48R is basically a set of TZ500 cassette-gearbox crankcases with a special factory top-end on them, with guillotine power-valves, a quite different stud pattern for the separate cylinders, and special porting,” says Nigel Everett of the OW48R motor, whose only weak point seems to have been the extractable gearbox—a fact confirmed by former works Yamaha TT-winner Charlie Williams, who also rode the Roberts bike at Assen and recalled the time he was leading the 1981 Senior TT in the Isle of Man by a comfortable margin on an OW48R, when the gearbox broke flat out in top gear around the fast sweeper at Ballacrie, just after Ballaugh. Ouch…

Thanks to the attention of his quality team of race mechanics, headed by Kel Carruthers with Nobby Clark and Trevor Tilbury alongside, that wasn’t a problem that Roberts ever encountered in a race in 1980—and it also didn’t feature on the impeccably restored reverse-cylinder bike at Assen. On this, a gearshift linkage which kept going over dead center before Everett fixed it for me, and underdamped fork settings which had the front wheel chattering a little on some of Assen’s banked, sweeping turns, were all there was to worry about.

With 18-inch slicks now unobtainable, Wilson runs his bikes on treaded Avon race tires, which probably have at least as much grip as the Goodyears that KR used to race with 20 years ago, and certainly allowed me to appreciate the Yamaha’s key advantage compared to its more powerful rivals—its more capable and forgiving handling.

The OW48R’s piston-port engine wasn’t as powerful as the more explosive disc-valves motors of the Kawasaki KR500 and Suzuki RG500.

The OW48R’s piston-port engine wasn’t as powerful as the more explosive disc-valves motors of the Kawasaki KR500 and Suzuki RG500.

Smaller, Faster

The OW48R feels quite modern for a 40-year-old racer, low and compact in build with a balanced setup and tight riding position, especially compared to the taller, rangier stepped-cylinder square-four Suzuki which was its main rival in its championship season.

It steers really well, and not only on faster turns as at the end of the Assen main straight, where I could maintain an improbably high turn speed after flicking down four gears in swift succession on the race-pattern gearbox while squeezing hard on the front brake lever to take advantage of the surprisingly potent brakes for such period Japanese stainless steel kit. Kenny told me he did not like them in a long race, but in shorter track outings they work okay—and I’m usually very dismissive of 1970s brake technology. Not this time.

But the Yamaha also steered well, flicking from side to side in the chicane, where its low, compact build and short 51.15-inch wheelbase made changing direction quickly easy and confidence-inspiring.

Despite being so short by later 500GP standards—but thanks also to the low center of gravity—the Yamaha was also stable over bumps. Although the Monocross rear end isn’t as compliant as modern rear suspension, it’s still a big improvement over the twin shocks it replaced. Suzuki took a long time to come up with their Full Floater rising-rate rear end as an answer to the Yamaha monoshock system, whose long nitrogen-charged DeCarbon shock with its separate gas canister, is fully adjustable for compression and rebound damping.

The short 53.15-inch wheelbase makes for dynamite agility on the Kenny Senior 500.

The short 53.15-inch wheelbase makes for dynamite agility on the Kenny Senior 500.

Better Brakes

Going back to the brakes, although the aluminum brake calipers each only have two pistons, the slotted Yamaha stainless-steel discs solidly mounted to their meaty aluminum carriers surprised me both by their effectiveness, as well as their initial response when you just touch them lightly to scrub off a bit of excess speed in a turn—though Kenny Roberts’ insistence on maxing out front disc sizes surely helps here.

Plus, it was noticeable when braking hard from high speed for the Assen chicane, and again for the National circuit’s tight Turn 1 hairpin, that the brake-operated hydraulic anti-dive on the Kayaba forks really minimizes weight transfer, by using caliper reaction to close a valve and increase compression damping, thus slowing front-end dive.

Though KR Sr. wasn’t a big fan of the system, frequently opting for non-anti dive forks with adjustable damping obtained by changing externally accessible jets, I found it added to the feeling of stability delivered by the accomplished Yamaha chassis, without at the same time resulting in that dead feeling you get from most other anti-dive systems, where you can’t feel what the front tire is doing because the hydraulics dial out front-end suspension response when trail-braking into a turn. Here, you can.

The King throws it up for the fans during the 1980 Dutch TT at Assen.

The King throws it up for the fans during the 1980 Dutch TT at Assen.

On The Pipe

There’s no denying that the OW48R’s piston-port engine simply doesn’t feel as powerful as the more explosive disc-valves motors of the Kawasaki and Suzuki, even if the YPVS power-valve system does help max out top-end power, without doing so at the expense of rideability.

Just as KR was later to tell me himself, I found you can’t crack the throttle wide open at low rpm exiting a slow turn like the Assen Nationale Kurve, or else the engine will bog down and struggle to get back on the pipe. It’ll pull okay on part throttle from as low as 6500 revs—but get it revving above 8000 rpm, keep up the turn speed, and you’ll be rewarded with good drive by the standards of the day, as well as a smooth transition into where you really want to be, in the strong powerband above 10 grand. From there to the engine’s peak at 12,000 rpm the power builds pretty strongly, though not in the same eager way as the rotary-valve bikes—engine acceleration is more progressive and user-friendly, but also not as fast.

Kenny chills with Aussie Kel Carruthers, the man he credits with helping him to his three world titles.

Kenny chills with Aussie Kel Carruthers, the man he credits with helping him to his three world titles.

In fact, Everett had fitted a set of later 38mm TZ500J Powerjet carbs to the Roberts bike, because they make more power on back-to-back dyno tests than the factory magnesium flat-slide carbs which came with the bike, which are also much harder to set upright, as well as to jet properly on the day.

But even with these, the Yamaha definitely wasn’t as fast as Chris Wilson’s ex-Kork Ballington KR500 Kawasaki I happened to be riding later the same day. And that narrow power band would have meant the OW48R’s extractable gearbox was a key element in its championship success, with the art of setting it up just right in terms of the right choice of ratios for every circuit (Kenny had a choice of four possible ratios for first and second gears, and three each for third and fourth) really critical, with zero over-rev on an engine that’s all done at just over 12,000 rpm.

Roberts took three of the eight rounds in 1980 to win his final world title.

Roberts took three of the eight rounds in 1980 to win his final world title.

Kenny Roberts really had to work hard to earn the third of his world titles, and the key element in allowing him to do so was the OW48R Yamaha’s more assured handling package—but 40 years on, nothing has changed. During the MotoGP era, Valentino Rossi and the now-retired Jorge Lorenzo won a succession of MotoGP world titles for Yamaha on a well-rounded YZR-M1 that, whether in 990cc or 800cc guise, always handled better than its Honda and Ducati rivals, while only rarely being as fast. So, just like nowadays, the key element in making the last of the piston-port YZR500 Yamahas into a world champion was the man who rode it.

King Kenny, we salute you.

This has to be one of the best-looking bikes ever to take to the Grand Prix grid, wouldn’t you agree?

This has to be one of the best-looking bikes ever to take to the Grand Prix grid, wouldn’t you agree?

Kenny Roberts Jr. 2000 Suzuki RGV500

One Better

Mission accomplished. After winning four GP races and finishing second overall in the final 500cc World Championship of the last millennium, with a bike which was the surprise package of the 1999 season, Kenny Roberts Jr. and the RGV500 Suzuki XR89 went one better in 2000.

KR Jr. clinched the world title two races early after again winning four races in the 16-race season—one more than anyone else—with a single DNF at Assen after the engine seized when he was seemingly set for a fifth victory. A total of four pole positions, nine rostrum finishes, and three fastest laps stamped King Kenny II and the XR89 as the dominant force in Y2K 500GP racing, ahead of Valentino Rossi in his 500GP debut season for Honda.

This came after the Suzuki rider took the championship lead in the third race of the season in Japan, and held it for the rest of the year, despite an obvious horsepower deficiency on the part of the RGV500 Suzuki’s twin-crank engine that Kenny was especially vocal about all year long. It just meant he had to work a little harder to succeed his dad as master of the 500 GP universe, exactly 20 years on after KR Sr. scored the last of his trio of world titles for Yamaha.

Roberts took the title lead in 2000 at round three at the Japanese Grand Prix and never looked back.

Roberts took the title lead in 2000 at round three at the Japanese Grand Prix and never looked back.

20 Years On

The chance to test the newly crowned 500cc World Champion’s bike came at Phillip Island in 2000. The previous year, I test rode Junior’s RGV500 at Jerez, where I’d discovered the bike’s crucial advantage—its sweet steering and refined handling. This was the product of the effective three-way collaboration between rider Roberts, the Suzuki design staff back home in Hamamatsu, and the late Australian race engineer and former top rider Warren Willing, which endowed the XR89 chassis with a level of balance and refinement that set it apart from its rivals. However, the ability to cut inside the opposition and hold a tight line in a slower bend that I discovered at Jerez was one thing—but the fast, flowing Phillip Island track posed a different kind of exam: was the Suzuki’s agility and poise in changing direction in tight turns only obtained at the cost of high-speed stability, which might compromise its performance on faster tracks?

Twenty-five laps of the Island later, I had my answer—as well as a vivid lesson in the phenomenal levels of skill needed to ride one of the final evolutions of a 500cc GP two-stroke.

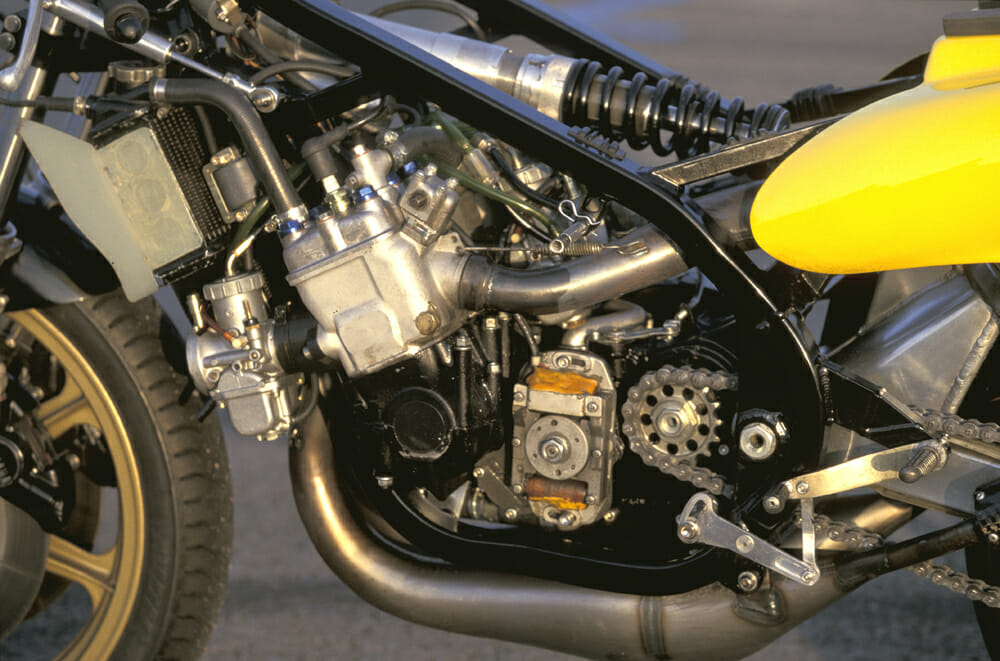

Stripped bare. Roberts complained bitterly about his Suzuki’s lack of acceleration—a deficit he could only make up with demon late-braking.

Stripped bare. Roberts complained bitterly about his Suzuki’s lack of acceleration—a deficit he could only make up with demon late-braking.

Reprogram The Brain

I needed to reprogram my brain to convince myself that what seems like an insanely fast entry speed for Siberia really was the right and proper way to ride the more-or-less guided missile that a 500 GP represented.

One lap, this time climbing away from Siberia, thanks to the Suzuki’s excellent traction when cranked over, I got such a good drive that I missed my cutoff point into the next right-hander at The Hayshed and went in too deep, which in turn put me wrong for all the rest of the hill up to Lukey Heights.

There, I was effortlessly out-braked by Kenny Roberts himself—complete with pitying shake of the head, before he gave me a master class in how to stop for the downhill MG hairpin immediately after.

That came after a different kind of lesson in my previous session, where I was busy complimenting myself about how late I’d left my braking for the balls-out first-turn Doohan Corner, waiting till the 150-meter [500-foot] board at the end of the main pit straight before knocking it back two gears from wide open in top, and braking pretty hard—when KR blasted past, still hard on the gas in top gear!

“I’ve done a ’31 round here, but only by not braking at all for Turn One,” confirmed Kenny laconically later. “I just hook it back two gears at the 100-meter [330-foot] mark and scrub off the speed on the tire. It takes a while to work up to that—but it’s one of the Suzuki’s main advantages—how much turn speed you can carry on it. But our big handicap is we are down on horsepower compared to the Hondas and Yamahas. If we can get away ahead of them in a race, we’re looking good to win it. But if we have a Honda rider ahead of us, every time he gets on the gas hard, he pulls distance on us before our bike responds, because they have better power. That makes it awful hard to get past—I can out-brake anyone on the Suzuki, but not if I’m starting from 20 yards back, because of the power deficiency.”

Cathcart tries to reprogram his brain to ride “the more-or-less guided missile.”

Cathcart tries to reprogram his brain to ride “the more-or-less guided missile.”

All The Feel

Even at my slower pace on the Suzuki, I could appreciate how well Kenny’s Suzuki kept up turn speed, with a good feel from the Öhlins fork adopted by the team midway through the 1999 season. It was ideally set up to give lots of feedback from the 17-inch Michelin front tire the team invariably raced with, rather than the 16.5-incher favored by other teams.

But lessons in maintaining momentum aside, it was the braking from high speed that took the most coming to terms with on the world champion RGV500—for sure, that’s where I lost most time. The previous year at Jerez this was the one aspect of the bike I felt able to criticize, and indeed its lack of stability under heavy braking was also commented on by some of Kenny’s rivals, including the man he succeeded as world champion, Honda’s Alex Crivillé.

At Phillip Island a year later, this was the single greatest obstacle to a faster lap time, especially in terms of relearning all my Superbike braking points to reflect the awesome effectiveness of the Brembo carbon brakes. Manufactured by the Italian firm from Mitsubishi composite material, which maintained heat longer and so gave better feel at lower lever pressures, as well as super-effective stopping at higher speeds, these were also more durable.

“The Suzuki team has consumed just three sets of discs per bike all season,” said Brembo technician Eugenio Gandolfi at the Phillip Island test, “but we’d prefer them to use smaller 290mm discs at Phillip Island, as they do at several other tracks to help keep up disc temperature in colder conditions. Only Kenny prefers the bigger 320mm discs for their extra performance at the several points of heavy braking from high speed in Australia.”

Like his father with Kel Carruthers, Kenny Jr. relied on another legendary Australian to help him to his title, the late Warren Willing (right).

Like his father with Kel Carruthers, Kenny Jr. relied on another legendary Australian to help him to his title, the late Warren Willing (right).

Supreme Stability

The Suzuki’s capable chassis proved just as forgiving around a fast, fearsome track like Phillip Island, as it is at a slower, switchback one like Jerez. It still changed direction so easily and felt beautifully balanced driving hard over the bumps exiting Siberia, shrugging off their effects effortlessly as it drove hard up the hill, holding its line perfectly as it did so.

Through the next fast right, though, it was better to take it one gear lower than expected to stay on line, with the engine singing at high revs but off the end of the torque curve—use a higher gear, and this had the effect of pushing the front wheel wide and making you back off to correct.

Under power, the Suzuki was so finely poised, only shaking its head once per lap over the big bump in Turn 12 leading on to the Gardner Straight past the pits, though that was probably down to a rear shock setting a little too soft for my extra weight compared to Kenny’s. Elsewhere, the XR89 chassis was ultra-stable—though if you squeezed the brakes to correct your entry speed once leaned over and committed to a turn, it did sit up and understeer straight ahead. This meant it rewarded a clean, precise 250 GP-style of riding that Kenny excelled in and once I worked up to it, I could keep up turn speed by taking lots of angle, which the extra side grip of the 16.5-inch Michelin rear allowed me to take advantage of when driving hard out of the exit.

Neat and tidy: This was the view most had of Kenny Jr. In 2000, but it didn’t get better for the American in 2001.

Neat and tidy: This was the view most had of Kenny Jr. In 2000, but it didn’t get better for the American in 2001.

Pushing, Pushing…

The only time the XR89 chassis felt nervous was when braking really hard—especially downhill into MG Corner—when the extra weight transfer supplied by gravity made an already awkward situation even worse.

Though Kenny Roberts said he used the back brake first to counter this, it really felt like a handful, especially compared to the more balanced behavior of Valentino’s rival Honda NSR500 I rode the following month in Jerez.

Ironically, this was particularly apparent at Honda Corner, where I’d come sweeping around the left-hander at what is now called Stoner Corner at high revs in fifth gear on the side of the tire, then have to brake really, really hard while still cranked over, for the bottom gear right-hand Honda hairpin immediately after.

The fearsome grip of the carbon brakes, coupled with the high-speed momentum, lifted the back wheel in the air as I was trying to pull the Suzuki upright, sending it waving around as the bike snaked under stopping—all of which made it very hard to pick a line for the turn and hold to it.

Twice I chickened out of trusting the front Michelin’s ability to make up for all this and take me through the turn at excessive speed on the wrong line and took to the escape road.

Mission Control for the Roberts Suzuki. Compared to a modern MotoGP machine, this looks positively prehistoric.

Mission Control for the Roberts Suzuki. Compared to a modern MotoGP machine, this looks positively prehistoric.

The Motor Game

It was the engine that was the greatest improvement between the Roberts runner-up bike I rode in 1999 and his title-winning motorcycle. This was because the bottom-end power, which Warren Willing confirmed back then was one of the bike’s weak areas, had been greatly improved—plus the transition into the stronger midrange zone around 10,500 rpm was smoother.

Compared to the meatier, more abrupt power delivery of the Honda at the same revs, the twin-crank Suzuki engine was now more user friendly, only just not as powerful as the more brutal, brusquer single-crank NSR500 motor. Arguably, though, it was now better low down than the Honda, so that exiting MG I could short-shift from first to second around 10,000 rpm while briefly upright, before flicking it into the long, long left-hander that followed, playing the responsive throttle to drive cleanly around and pick up speed as the track opened out.

This let me reap the benefit of the 2000 Suzuki’s revised porting and electronically controlled variable-dimension exhausts (same effect as a power valve) to save me from having to do the rather notchy bottom shift gear change while leaned over when it’d get the rear wheel slightly unhooked.

The quickshift gear change on the race-pattern gearbox was nicely set up, though I’ll admit to not paying too much attention to the row of five red shift lights that illuminated in succession across the top of the analog tacho, because I was too busy holding on tight as the Suzuki’s front wheel pawed the air on such a daunting track.

Two kings: Roberts Jr. (left) and Roberts Sr. The only father and son 500cc World Champions.

Two kings: Roberts Jr. (left) and Roberts Sr. The only father and son 500cc World Champions.

Remembering what Warren Willing had told me the previous year as I struggled to keep the front wheel on the ground exiting the final turn at Jerez before the pits, I coped with the similar power wheelies out of Siberia by revving the Suzuki hard so that the engine fell off the end of the torque curve, which paradoxically provided a better drive than using the fat part of the power band around 11,500 revs. That was better for my heart rate, too—at least I could now see where I was pointing it for the next turn, without landing the front wheel with the ‘bars all crossed up.

King Kenny II may have had his work cut out to defend his 500 GP world crown in 2001 after Suzuki suspended two-stroke R&D in favor of its new four-stroke MotoGP project. But he won it fair and square in 2000 on a Suzuki which proved to be the best all-around package on the grid—just as his dad did 20 years earlier on a similarly underpowered Yamaha. Like Father, like son.CN