Larry Lawrence | May 21, 2019

Archives: We’ll Miss You Burritto

One of my most memorable evenings of racing was spent hanging out with Gene Romero. It was the Indy Mile and the 1998 AMA’s Dirt Track Grand Championships. I was doing PR for the event featuring the leading up-and-coming amateur flat track racers and Gene was the honored guest of the event. If you’ve ever been to one of these amateur events you know with all the classes they tend to drone on, but hanging with Gene made watching kids racing until 1 am bearable, enjoyable even.

Archives: We’ll Miss You Burritto

Gene Romero flashes his million-dollar smile.

Gene Romero flashes his million-dollar smile.

Gene, American Motorcyclist magazine senior editor Grant Parsons and I were watching the racing from the grandstands. Gene was entertaining us with stories of his racing exploits over the years and we were soaking in every minute. We loved being the private two-person audience to one of racing’s all-time great raconteurs and Gene was definitely in his element. In between stories, Gene would give us his expert opinion on what needed to be done with track prep. “It’s almost where it needs to be right now,” Gene said looking over the dirt on Indy’s famous mile oval. “All they need to do is spritz it. Just a light mist and it’ll be perfect.”

For years after, whenever Grant and I ran into each other at an event, all we had to do to crack each other up was repeat Gene’s line, “Just spritz it!”

That was Gene Romero. He was the kind of guy you remembered with a smile. Over the years I’d occasionally call up Gene for a quick chat. We’d talk about whatever issue was going on in the world of motorcycle racing at the time, and inevitably Gene would have the answer to world’s problem. And I would usually get a bonus of another epic Gene story I hadn’t heard before.

Gene Romero leads the pack in front of a massive crowd at the 1969 Sacramento Mile.

Gene Romero leads the pack in front of a massive crowd at the 1969 Sacramento Mile.

I first met Gene when he was managing Honda’s dirt track program, which was based out of my hometown of Indianapolis. He was freshly retired from racing at that point, so he could give Bubba Shobert and Ricky Graham great pointers in dialing in Honda’s new RS750 racing machine. As a young race reporter for Cycle News, I quickly learned I could always get a good quote from Gene. And Gene was always accommodating, even to a new reporter who was getting his first opportunity to cover national races at that time.

I once sat next to famed auto racing reporter Robin Miller on a plane coming back from Charlotte, and he told me some great stories about he and Gene promoting some indoor flat track races, one particular at the old Cincinnati Gardens arena where practically no fans showed up and they lost their shirts. Robin said that race made him realize he didn’t have the stomach (or the funds) to be a race promoter. But those misfires didn’t phase Gene, he kept right on promoting racing events for the rest of his life.

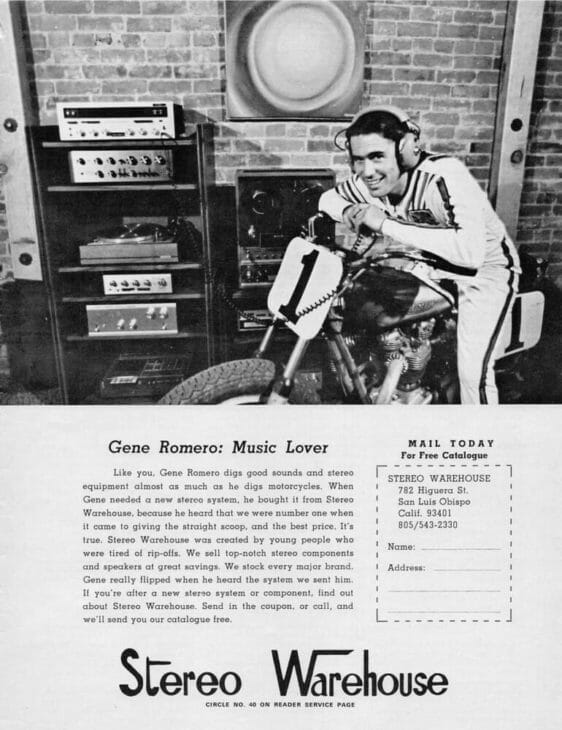

Stereo Warehouse was one of Gene Romero’s many sponsors.

Stereo Warehouse was one of Gene Romero’s many sponsors.

Robin also told me a funny story about Gene conveyed to him by Dave Despain. Dave was an aspiring flat-tracker in the early ‘70s and they were running a flat track the Sedalia, Missouri, but the track was so rough and rutted all the national numbers refused to run. “Send out those novices,” barked Romero pointing at Despain. “They don’t know any better.”

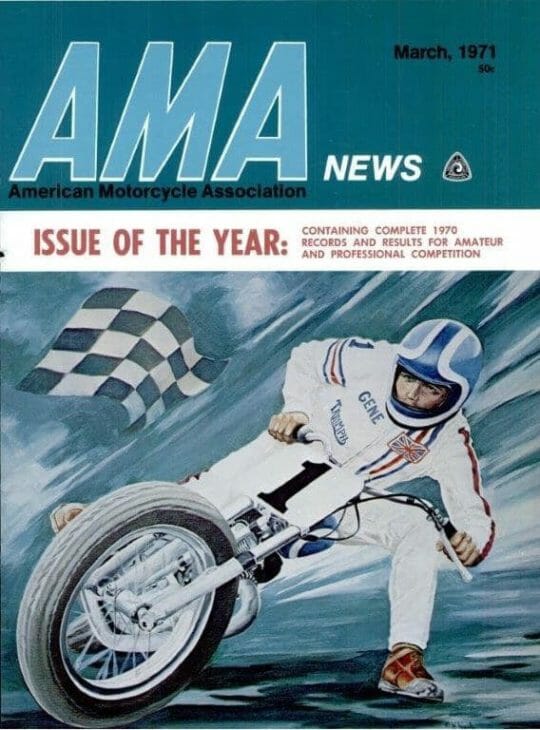

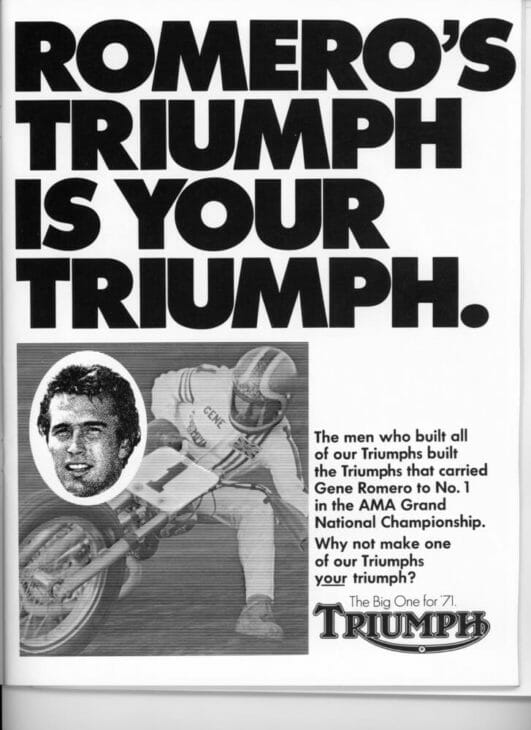

Even though he raced for other makers, Gene will forever be linked to Triumph. It was with the British brand that he won his 1970 AMA Grand National Championship.

“Riding for Triumph was really cool, they were wonderful,” Romero said, after being named Grand Marshal for the AMA Vintage Motorcycle Days at Mid-Ohio in 2009. “I had been on multiple brands with factory rides, but I kind of grew up around the Triumph thing, and I have some really fond memories of them. It’s funny. The real hell-raisers were kind of thought to be on the Triumphs, and that suited me just fine.

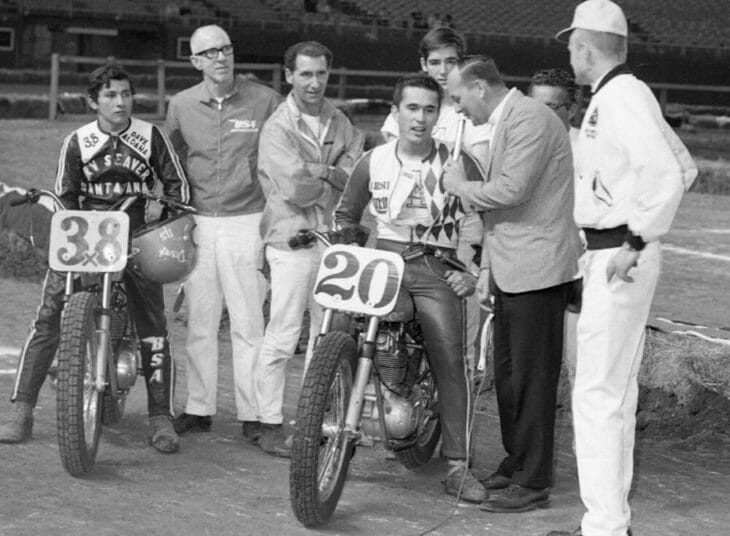

Gene Romero being interviewed by longtime AMA racing announce Roxy Rockwood at Houston in 1969. His friend and fellow racer David Aldana looks on. Aldana said Gene looked out for him when he first entered the pro ranks.

Gene Romero being interviewed by longtime AMA racing announce Roxy Rockwood at Houston in 1969. His friend and fellow racer David Aldana looks on. Aldana said Gene looked out for him when he first entered the pro ranks.

“Guys like Skip Van Leeuwen, Dick Hammer, who were kind of the real pioneers on Triumph, and Neil Keen and Evel Knievel, who actually sponsored me for a year. Knievel impressed on me the whole idea of promoting yourself, and the fact that if you ask for the moon, sometimes you’ll get it.”

That last point was one of Gene’s last legacies in the sport. He wasn’t afraid to ask for big money from sponsors and sometimes he landed those sponsors during a time when very few, if any, in motorcycle racing were bringing in those kinds of deals. He hustled and brought in big-time sponsors to his racing programs from outside the motorcycle industry. At one point or another he had Ocean Pacific (swimwear), Anheuser-Busch, Valvoline and a stereo company as sponsors. As mentioned, Evel Knievel even backed his racing team one season. Gene was one of the first to show up with leathers that were custom designed featuring a sponsor’s logo (Busch Beer) emblazoned across the entire outfit, top to bottom.

Gene Romero made the cover of the AMA’s magazine after he was voted Rider of the Year.

Gene Romero made the cover of the AMA’s magazine after he was voted Rider of the Year.

Gene came up in an era when motorcycle racers didn’t make a lot of money, so he was always hustling, looking for an angle to earn a little extra cash. Used to operating that way most of his life to make a living, meant often when you talked to Gene about making an appearance, even if he was being honored, the first thing he wanted to know was how much he was going to be paid – and his fee wasn’t cheap.

The other thing most people don’t know about Gene is that he wasn’t a natural on a motorcycle. He had to work really hard at getting to the level he got to and much of it was by sheer will and hours of practice. It took him several years to get to the point that he was consistently competitive at the national level. He didn’t ride too much recreationally. If he was on a motorcycle, he was racing.

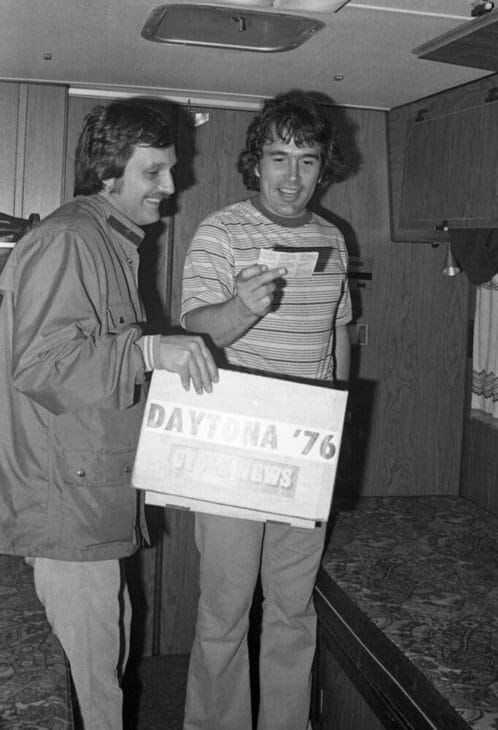

Former Cycle News editor Jack Mangus and Gene Romero share a laugh at a race in the 1970s.

Former Cycle News editor Jack Mangus and Gene Romero share a laugh at a race in the 1970s.

His good friend David Aldana laughs when he talked about the time he talked Gene into going trail riding with some of their buddies. “He couldn’t ride a dirt bike worth a darn,” Aldana grins. “We’d get to a steep hill and somebody would have to get off and ride his bike to the top.”

But everybody loved having Gene around. When he and Aldana got together, you might as well forget it, they were going to own the floor. The best part was that no one minded. They knew Gene and David’s stories were the best you were ever going to hear.

A lot of people in the industry I’ve talked to since Gene died say he’s gone too soon. While that’s true in a sense, if you heard about a chain-smoking motorcycle racer who came up in the lethal racing era of the 1960s, who would go on to become national champ, win one of the biggest races in the world then live to just shy of 72, you realize it puts things in a completely different perspective. He lived a rich and full life.

We’ll miss you Burritto.