In The Paddock

COLUMN

There’s a couple of riders currently ruining racing. They’re just too good.

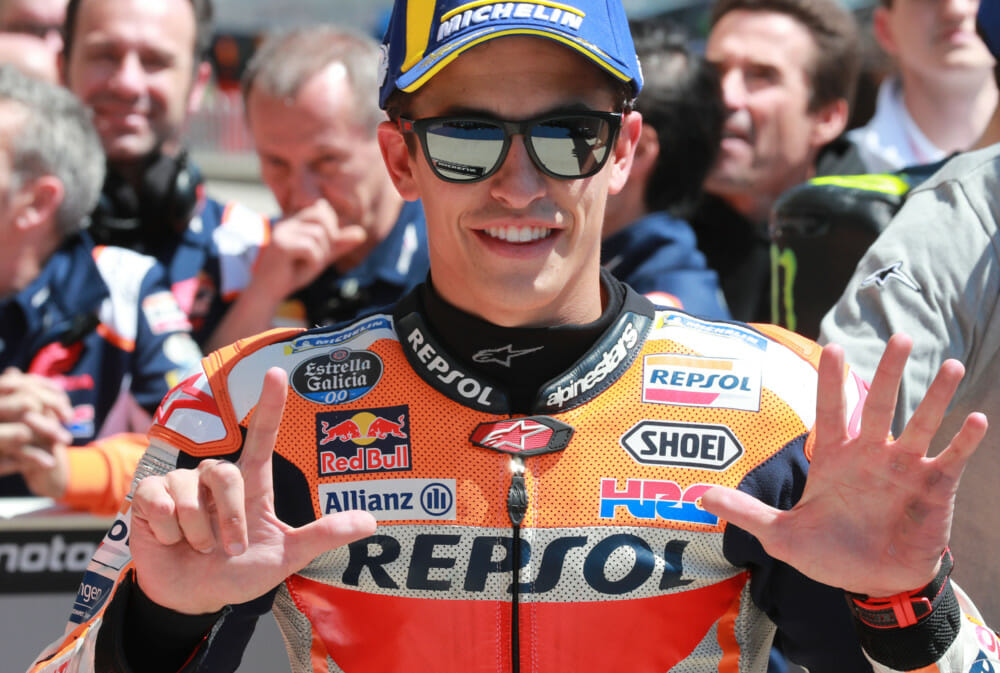

I’m talking about Marc Marquez and (over in the Proddie-bike paddock) compatriot Alvaro Bautista.

Admittedly, Marquez demonstrated a comforting streak of humanity at the last race in Texas, by falling off. But he had by then set his seventh successive pole position at the fast and complicated CotA circuit, and had built up a commanding lead, ready not just to take a seventh straight CotA win, but repeating his utterly dominant performance of two weeks before in Argentina, and in the championship five times over the past six year.

But displaced ex-MotoGP rider and former 125 World Champion Bautista, riding the new V4 Panigale Ducati much faster than anyone else on the MotoGP-inspired street bike, hasn’t come close to being beaten once in the first four WorldSBK weekends, taking every Superpole, every Sunday sprint race, and every main race, too.

Why should they win so much? It just spoils everything for everyone.

This at least is a view clearly cherished by the control-tower cronies who run both series. Why else would Dorna and their FIM allies conspire to make racing more equal?

In general life, it is humane to succor the disadvantaged and to help make things fairer for all. I’m not so sure that an active social conscience is quite so desirable at World Championship level. It’s hard for excellence to thrive when it is hobbled at the source.

And what is a World Championship if it is not about excellence?

In MotoGP, the thrust of dumb-down regulations includes limited fuel and engine numbers, frozen engine development and restricted testing, along with control tires, electronic software and hardware, and clamped-down aerodynamics. All of it has come in the name of cutting costs. But the hidden agenda (not so hidden back in the days of production-based CRT bikes) is to restrain any sporting advantage of the big-spending factories by limiting their engineers’ access to adventure.

This secondary aim has been much more successful than the so-called primary one. Cost-wise, factories still spend just as much as they like (or can afford)—Honda a heck of a lot more than Aprilia, for instance. Or Suzuki, making the recent Texas win all the more sweet, even if it took crashes and a breakdown to the three factory Hondas for it to be achieved.

The technical socialism is all more blatant in WorldSBK. Always has been. Fair enough: these are production-based bikes and not a field for prototype experimentation. There have been decades of attempts not to help the slow guys get quicker, but to slow down the fast guys—the very opposite of the ethos of racing.

Remember the intake restrictors? The different engine capacities allowed for different numbers of cylinders? And how in spite of it all, the same guys kept on winning?

It’s more sophisticated now, with a complicated and regularly reviewed system of component control via concession parts, and on top of that controlled rev limits. These are updated every three races to make sure that nobody gets too big for his boots.

In this way, after Bautista and the new V4 Panigale had won every outing at the first three rounds, Ducati’s rev limit was cut from a giddy 16,350 rpm to 16,100; Honda’s went up from 14,550 to 15,050—a jump of twice the usual 250 rpm to take account of its feeble early showing.

Did it make much difference at Assen? Nothing you’d notice. Bautista still took Superpole and won both races. The best Honda result for Leon Camier was 10th place.

Mediocrity is sought. As if the best outcome of any race is a mass dead heat. In the distant past, at tracks like Brooklands, there was actual handicapping. The slowest guys started first. Which actually does sound like quite fun but turned out to be open to all sorts of corruption.

Can mediocrity be found just by regulations?

Back in the late 1960s, the FIM banned technical complexity (like Honda’s five-cylinder 125 and the multi-geared multi-cylinder two-strokes of Suzuki and Yamaha, with hairs-breadth power bands) from bringing the factories under control.

More recently there was the talk of how to slow down Valentino Rossi. One idea, borrowed from saloon car racing, was that every victory should oblige the rider to carry extra weight, with lead ingots to be cable-tied to the chassis. This was rejected, but when somebody suggested that maybe Rossi’s bike should be fitted with a sidecar, he was only half joking.

Now it’s Marquez who should be obliged to carry a passenger, unless, as he demonstrated at CotA, he can find his own way to avoid winning everything by miles.

You know what? Strap on as much ballast, as you like. If he doesn’t crash, he’ll probably still win anyway.CN

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Click here for all the latest motorcycle Industry News on Cycle News.

Click here for all the latest Road Racing news.