Rennie Scaysbrook | January 19, 2019

The Incredible Story of Beppe Gualini

Beppe Gualini is the man responsible for the day-to-day running of Ducati press launches, but his story is so much more than that.

Gualini exits a village in Niger at the finish of the Special Stage on the Suzuki DR 750 Big.

Gualini exits a village in Niger at the finish of the Special Stage on the Suzuki DR 750 Big.

In Africa, 40 years ago, was dangerous,” says Italian Beppe Gualini. “Was a problem to enter, because you go completely into a war. You can go to Algeria, but you don’t know if you come back.”

As you roll through life, people like Gualini are ones who stick in your mind. They bury a place in your memory, for people like Beppe are prime examples of living life to its maximum potential, to leave nothing on the table when your day of reckoning comes.

Photography by BG Archives

Beppe is better known these days as the man who organizes and marshals the rides for Ducati’s international press launches, ferrying journalists from one photo stop to the next, at a pace he’s learned to live with compared to his previous life as one of the pioneering Italians for African rally racing.

Gualini in his day job, putting machines like the Ducati Multistrada 1260 Enduro through its paces at the Ducati Riding Experience center.

Gualini in his day job, putting machines like the Ducati Multistrada 1260 Enduro through its paces at the Ducati Riding Experience center.

A veteran of 65 rallies on the African continent, Gualini was an integral part of the golden years of the Paris-Dakar—the treacherous, life-affirming mission from the French capital of Paris to Dakar’s capital of Senegal on the coast of West Africa, back when there were no phones, no GPS, just you and your navigational wits against the beast that is the Tenere Desert.

Born into a family living below the poverty line in Bergamo, Italy, Gualini’s introduction to motorcycling came after he found an abandoned machine in the local dump that he fixed to running condition with the help of his mechanic father.

“Bergamo is the town where was [I was] born,” Gualini begins in very good, Italian-English. “There you have the Valli Bergamasche enduro race, because in Bergamo there are the mountains and there are two valleys, and this race ran through those valleys.”

Senegal, Dakar, 1987. Gualini rode three years with Suzuki, one on the DR600 and two with the legendary DR 700 Big.

Senegal, Dakar, 1987. Gualini rode three years with Suzuki, one on the DR600 and two with the legendary DR 700 Big.

Engulfed by a love of two wheels, Gualini did not have the financial means to compete as a young lad. Instead, he placed a priority on education, going on to attain a degree as a teacher in Physical Education.

But, even though competing was not yet an option, traveling was, and with a Ducati Scrambler 450 under him, in 1979, the young Gualini set off for Africa.

“I was in Algeria and the military stopped me in a control and ask me [for] money. They said, “If you want to pass, you pay.” I said, “Sorry, I don’t have money”. “Okay, f— off,” they said. “You don’t pass here”.

“So, I stop there. I sleep one night in the sleeping bag, me and my bike. I go the second day with the passport. They said, “Okay, money!” I say, “Sorry, no money”. They said, “F— off. You don’t pass.” Was like this for three days.”

Little did 22-year-old Gualini know on the third day, his life was about to change forever.

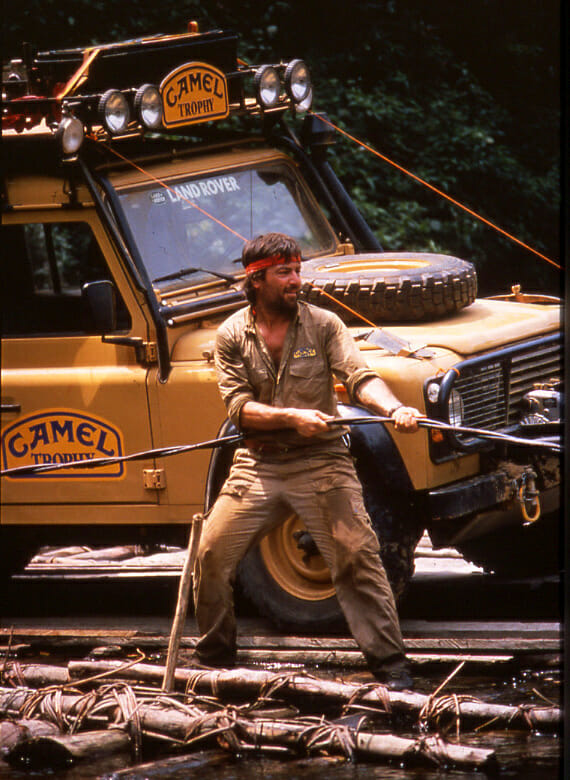

Gualini also competed with distinction on four wheels, with a record of 15 Camel Trophy starts, widely regarded as the toughest race ever conceived for cars. Here, Gualini does his best to cross a river in Borneo with a handmade wooden raft.

Gualini also competed with distinction on four wheels, with a record of 15 Camel Trophy starts, widely regarded as the toughest race ever conceived for cars. Here, Gualini does his best to cross a river in Borneo with a handmade wooden raft.

“The third day I see a car with a sticker with a number and a sponsor. It was a magazine from France, and after, I see a motorbike with the number.

“I said, ‘What is this?’”

“Oh, it’s a race,” the rider told me.

“Which race?”

“We start from Paris and we go to Dakar,” he told me.

“I meet the first Paris-Dakar. The [rider] said they will cross the Tenere Desert. That was my dream. Like a sailor crossing the ocean. So, I jump in the convoy of the Paris-Dakar, tell the military to f— off, and I cross the border.”

The original Paris-Dakar, running from 1979 to 2007, was a far cry from the manicured South American spectacle it is today. A 12,400-mile kilometer epic that originally ran from Paris to Algeria, through Mali, then skating the outskirts of Mauritania to Senegal (in later years the race route would change and take in destinations such as Libya to Africa’s central northeast, Tunisia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, with the 1992 race spanning the entire continent of Africa north to south) the Paris-Dakar was the brainchild of French explorer Thierry Sabine, a man who became obsessed with the Tenere desert after getting lost in it for three days while competing in the Abidjan-Nice race in 1977.

Gualini chills in the Namibian desert with the mighty Yamaha Super Tenere. The 1992 race changed from Paris-Dakar to Paris-Cape Town and spanned the entire length of Africa.

Gualini chills in the Namibian desert with the mighty Yamaha Super Tenere. The 1992 race changed from Paris-Dakar to Paris-Cape Town and spanned the entire length of Africa.

Gualini had a similar feeling of the never-ending Tenere terrain on his return to Italy, and knew he found his calling.

“It took two years to get the money to buy a [new] bike,” Gualini said. Working odd jobs, including as a lifeguard, and with rallying gaining momentum as a sport in Europe, Gualini decided to enter Pharaohs Rally in Egypt on a 125cc Fantic two-stroke.

Running 560 miles south non-stop through the night from Venice to Brindisi on the little Fantic to catch a three-day ship to Alexandria in Egypt was another experience for Gualini.

“I jumped on the motorway with the bike that is not allowed. If the police see you, you are in prison,” Gualini says. “With the petrol in the tank, I was putting in the oil because I have the two-stroke without [pre] mix. So, I was putting [oil in] during the ride without a stop. Just open the tank and put oil. Big, white smoke everywhere!

“When I arrived, the boat was closed. It was 6 a.m., but the captain sees me. I have a backpack, I have a spare tire on the back. He says, ‘Who is this stupid man?’ But they stretch the rope and I get in.”

Paris-Cape Town, 1992. After being hit up the butt by the official works Peugeot, Gualini crashed and smashed his radiator. After 30 minutes of repairs, he was on his way and finished the rally 10th overall again as a privateer.

Paris-Cape Town, 1992. After being hit up the butt by the official works Peugeot, Gualini crashed and smashed his radiator. After 30 minutes of repairs, he was on his way and finished the rally 10th overall again as a privateer.

What followed was the kind of thing movies are made of.

“It was really hard because I was not French. My name was not Beppe, it was “The Italian” to the French officials. There were a lot of French guys with 125cc motocross bikes, with big tanks in aluminum, and cooling pumps to pump the petrol to the carburetor. Also, many [riders] have a mechanic and all this stuff. I thought I was f—ed. But I win the category in 125 and was 26th overall with 156 riders, because I was good in navigation.”

Gualini went from nobody to a minor celebrity almost overnight on his return to Italy. Within months, he was featured in renowned Italian publications Motociclismo, Motocross and Motosprint, their covers glowing with an image of the Italian adventurer on the 125cc Fantic and the great Pyramids of Egypt in the distance. Then the phone started ringing.

Gualini styles it for the cameras in front of the Great Pyramids after claiming victory in the 125cc class of the Pharaohs Rally, 1982. This shot landed on the front cover of many magazines in Italy and made Gualini a rally star almost overnight.

Gualini styles it for the cameras in front of the Great Pyramids after claiming victory in the 125cc class of the Pharaohs Rally, 1982. This shot landed on the front cover of many magazines in Italy and made Gualini a rally star almost overnight.

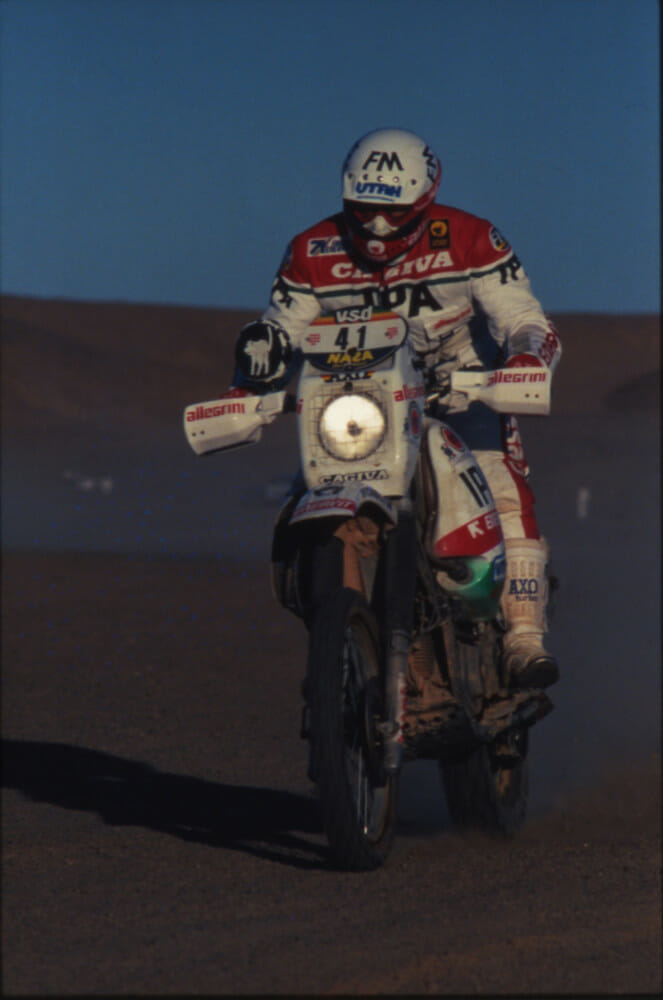

“Honda, Yamaha call me. I said, ‘You put the money, the best now.’ But after the Pharaohs Rally, I also did the Atlas Rally (Morocco) with the Cagiva 125, because Cagiva said, “Come with us.” So, I choose Cagiva.”

Success with the first Cagiva four-stroke, the 350 Ala Rossa (Red Wings) in the Pharaohs Rally in Egypt and victory in the only edition of the Norwegian Island Rally (otherwise known as the Dark Desert rally where riders traversed sections of volcanic lava) followed, with Gualini gaining a reputation as a man who could find his way.

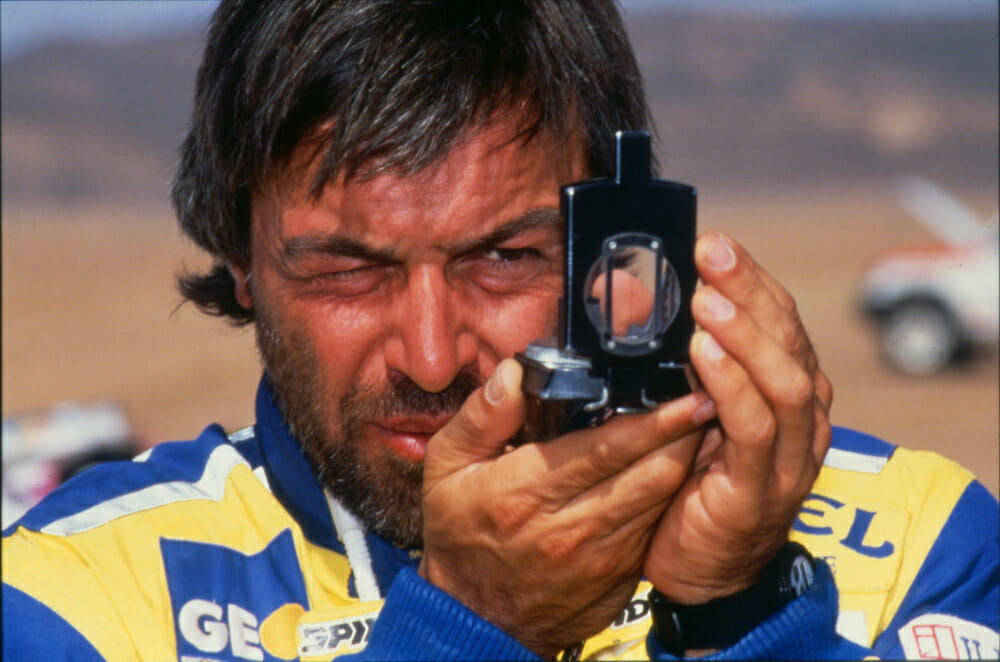

“I have a lot of big results because I was good in navigation,” Gualini says. “When I was riding a lot alone, I have knowledge of a compass, and of maps. You must be very careful in the desert to read the compass, because many times you have no reference point. Sometimes in the Paris-Dakar, I would arrive in the stage finish and 80 riders would be lost in the desert. I make a lot of experience with my extreme trips. It is very easy to get completely lost in the desert. If you do two degrees of difference with 80 kilometers, you are out by 22 kilometers. So, for this reason, for me it was important [to know] the navigation, because the navigation give you the possibility to obtain great results, especially in the Paris-Dakar.”

Paris-Dakar, 1988. Gualini checks the direction in Algeria before the start of the special stage. Navigation was always one of his strong points.

Paris-Dakar, 1988. Gualini checks the direction in Algeria before the start of the special stage. Navigation was always one of his strong points.

In 10 attempts of the Paris-Dakar, always as a privateer with the backing of Camel cigarettes, Gualini finished the event eight times and won the Marathon category three times in a race that took a staggering 22 days to complete with no rest day. The Marathon riders are not permitted to change key components on the motorcycle—engine, forks, frame, swingarm, etc.—so the rider must be gentle on his equipment to ensure he makes it to Senegal.

Gualini on the legendary Cagiva Elephant. “It had the Ducati 750 motor and was so powerful! It was a wild horse on the sand, fast but hard to ride. This was the first prototype.”

Gualini on the legendary Cagiva Elephant. “It had the Ducati 750 motor and was so powerful! It was a wild horse on the sand, fast but hard to ride. This was the first prototype.”

“Those are the most important [victories in his career]. I never have assistance. Only with my backpack. [It is] a big achievement because [it] means to sort out any problem. The only two races I don’t finish was a mechanical problem that I fall down for the Paris-Dakar with the Honda Africa twin. I was 10th overall. I was catching an official rider, four hours in the desert, and the shock absorber exploded completely. So, I had an accident.

“Another time we had an accident was in the dunes. There was another rider that was for two months in a coma. The bike arriving [on] the head, break the head. When I arrive, I don’t have the power to overtake, so I jump from the bike. I roll over. I don’t have any accident rolling on the dunes, but my bike land on my head. So, I broke the ligaments. Was the only two accidents I had.”

The Paris-Dakar is legendary not only as a motorsports event, but as test of human endurance. Sometimes the power of the mind outweighs the drive of the body, pushing it to the outer limits of its physiological design.

On the beach of Dakar, 1986, before the start of the last stage along the sea.

On the beach of Dakar, 1986, before the start of the last stage along the sea.

“The first Paris-Dakar, I ride 72 hours without sleep and without eating,” Beppe says. “Only to fill [gas] up in the middle of the desert, negotiating the price of the petrol in a drum of 200 liters!”

Read that again. The man rode for three days and nights, non-stop, with no sleep or food.

“I arrive at the finish of first day and the official said, ‘Beppe, move.’ I fill up the tank and go.

“No eat, no sleep. I fell down several times because I was sleeping [on the bike] and I don’t use the goggles because I need fresh air. So all the sand come in my eyes and I have conjunctivitis. My eyes were completely finished, so I don’t have good visibility. Was to the limit of my capacity.

“The people said, ‘shit, you can’t ride 72 hours.’ Okay. I have done it. But only with the brain. I say, if you have the brain, and no physics, you can achieve. If you have physics and no brain, well, I have seen world champions of motocross and great American, Italian, European, and French riders arrive, and after two days, they are crying in the desert. They have the fear. They do not see the exits. Don’t see the finish, only desert. They cry, and they leave the Paris-Dakar.”

Gualini powering through the Angolan jungle during the massive 1992 Paris-Cape Town event on the Yamaha Super Tenere.

Gualini powering through the Angolan jungle during the massive 1992 Paris-Cape Town event on the Yamaha Super Tenere.

Riding through countries that were conflict zones bought with its own set of challenges for the Paris-Dakar field.

“What I say all the time, remember, that you are sure you are starting but you are not sure you are coming back,” Gualini says. “For three times in Paris-Dakar they shoot at me, the military. Tried to kill me. But [I] was not shot. We were in a civil war in Angola. So, you take thousands of risks you can’t imagine.

“One time a truck exploded in the desert on a landmine. In the road book, in Mauritania, there was ahead, ‘Danger, Warning.’ There were mines on the road. You have to follow the line because [it] was near the border. The truck moved 10 meters off and explode. It’s so hard, so risky. It’s like going to Afghanistan. Could be you never come back.”

1992 Paris-Cape Town. Gualini powers through the treacherous fesh-fesh (“sand like talcum power”) in Cameroun in central Africa. The Super Tenere suited Beppe, this edition having a standard motor that was good for 120 mph but with official Yamaha factory race suspension.

1992 Paris-Cape Town. Gualini powers through the treacherous fesh-fesh (“sand like talcum power”) in Cameroun in central Africa. The Super Tenere suited Beppe, this edition having a standard motor that was good for 120 mph but with official Yamaha factory race suspension.

But there were other, happier stories Gualini keeps close to his heart regarding the world’s most famous races, including when, on the Atlas Rally, he broke a piston and was stuck in the middle of the Moroccan desert with a dead motorcycle.

“I have the Cagiva in the second race, the Cagiva 125 two-stroke,” Gualini says. “There was a big storm, so the air become less [dense]. When I closed the throttle, the piston, small like a finger, stopped the engine. No compression. I opened the engine, saw the piston, and said, “f—. I have no possibility [to fix the engine].

Paris-Dakar, Libya, 1985. Gualini offers up his front wheel to official Cagiva rider and close friend, Giampaolo Marinoni, after the latter destroyed his magnesium hub. Later, the Cagiva truck arrives with a new wheel for Gualini, who arrives at 4 a.m. and starts again at 5 a.m. Tragically, Marinoni is killed in the last Special Stage of the rally in Senegal.

Paris-Dakar, Libya, 1985. Gualini offers up his front wheel to official Cagiva rider and close friend, Giampaolo Marinoni, after the latter destroyed his magnesium hub. Later, the Cagiva truck arrives with a new wheel for Gualini, who arrives at 4 a.m. and starts again at 5 a.m. Tragically, Marinoni is killed in the last Special Stage of the rally in Senegal.

“I have my jacket with all the engine on the ground. Then start to come some village people, children and old men, and say, ‘what do you want to do?’ I say, ‘nothing.’ I can do nothing. I can’t weld. I can’t weld a piston because it’s aluminum. I need arc welding.

“A young man said, ‘soudage de l’arc village!’ [There is an arc welder in the village]. So, I take I think $100. I tear it in half. I said, ‘keep it. I give you the piston. If you come back, you have the other [half].’ It was a lot of money.

“The guy start with a bicycle and disappear. Disappeared and soon it becomes night, and arrives the last car of the convoy with the doctor who said, ‘what are you doing? You jump with us in the car?’ I said, ‘no.’”

“He told me I must sign [a release document].”

“‘If you refuse, after, is your problem,’ he said. “I have the worst night.

“It was I think 11 p.m. or midnight. If I sign [the release document], I am f—ed. But my feeling was I think the guy could arrive. At 1 a.m., I hear the bicycle. He arrive with the piston! I put in the piston, but we have a big problem because the welding was too high. So I start to clean [the piston] on a stone. There was an old man watching who said, ‘Stupid! This is the good stone,’ so he give me the good stone to do [grind down the piston]. I spent I think half an hour to clean all the piston. I put inside the engine, try to start. No start. But, there were children because they stayed with me all the time. Children and the old man, and he said, ‘Push! Push!’ and the engine starts. I finished the rally and won the category. When I said that I got the piston welded in the desert, nobody believed me.”

With the madness of 65 African rallies now firmly in the rearview mirror, Gualini knows he’s lived a special life many can only dream of.

“For each Paris-Dakar, there are a thousand stories. When you start, and each night you arrive in the finish, you are like a family.

Italian Gualini still has a burning love for two wheels, although the competition days are behind him.

Italian Gualini still has a burning love for two wheels, although the competition days are behind him.

“What is my satisfaction, I was not only in Italy but in all the world and all of Europe, I was the most famous because I was what a rider dreamed [of]. I was a private rider that with his energy, his founding sponsor, and race alone without mechanic. I was the first Italian rider to do an African rally. I am very thankful for my life.

“I am a lucky man because I have the opportunity to live real adventures and I can tell these stories.” CN