Larry Lawrence | November 21, 2018

Archives: The Bavarian Underdog

When motorcycle road race fans think of BMW and Reg Pridmore, the first thing that comes to mind is the impeccable Butler & Smith BMW R90S Pridmore raced to the inaugural AMA Superbike Championship in 1976. Lesser known is the Butler & Smith R75/5-based machine Pridmore campaigned for four seasons in the old AMA Formula 750 National Road Race class beginning in 1972. Without the knowledge gained by way of development of the R75/5 (and later /6 engine) Formula 750 machine, the championship R90S Superbike would have never been possible.

Archives: The Bavarian Underdog

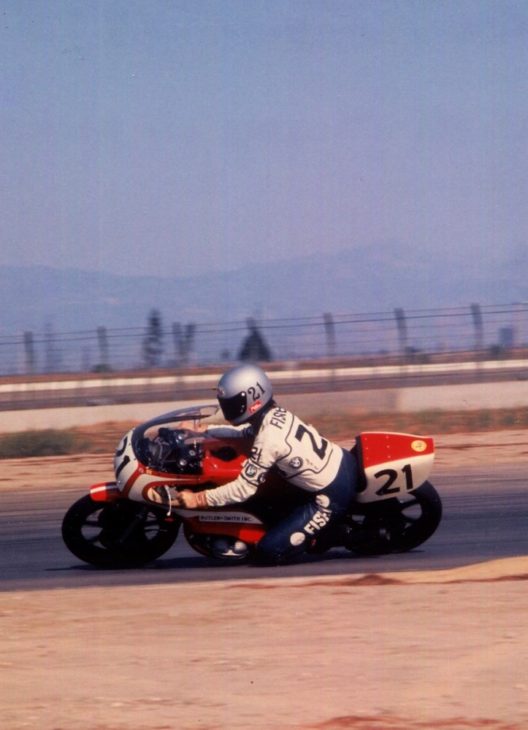

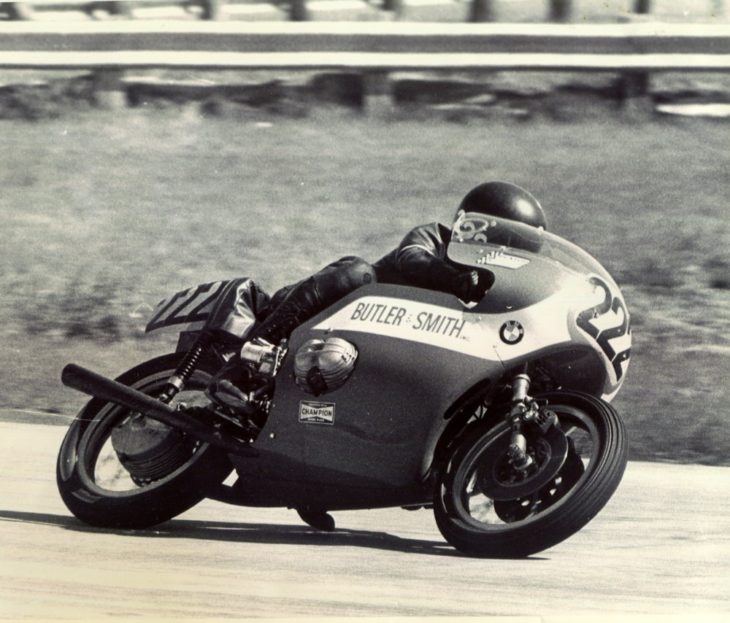

Gary Fisher at Ontario in 1975, racing the final version of Butler & Smith BMW F750 machine. It featured a monoshock rear suspension and Rob North chassis. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

Gary Fisher at Ontario in 1975, racing the final version of Butler & Smith BMW F750 machine. It featured a monoshock rear suspension and Rob North chassis. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

BMWs had been road raced in AMA Grand National road race competition from the beginning. Riders like Joe Tomas, Stan Myers and Ed Labelle earned solid top-10 finishes at nationals held in Daytona Laconia and Watkins Glen, but by the early 1960s the BMW marque was gone from AMA national competition.

When it first appeared at an AMA Road Race National in 1972, the Butler & Smith BMW F-750 drew a lot of attention. People know today that BMW can built excellent sport bikes, but understand that in America in the early 1970s BMWs were considered an old man’s touring bike. Reliable, solid and steady to be sure, but fast and nimble? No way!

Butler & Smith’s boss, Dr. Peter Adams, was looking to shake BMW’s stodgy image as an old man’s touring machine. In 1969 Adams authorized a small group within Butler & Smith to begin working on building racing motorcycles. Working part time on the project was an ex-Bultaco-backed motocross racer named Udo Gietl, who would later come to fame for leading both BMW and Honda’s successful AMA Superbike programs.

Gietl, with assistance primarily from Helmut Kern and Miles Rossteucher, built BMW /5 Series Boxers that were fielded successfully on the club level by Kurt Liebmann and Justus Taylor on the East Coast and Reg Pridmore out West. That year a pair of Butler & Smith BMWs went 1st and 2nd in an endurance event in Danville, Va., at what is now Virginia International Raceway. Development continued and BMW had excellent success in the low-key world of American and Canadian endurance racing. That spurred BMW on to develop a short-lived AMA Formula 750 (later called Formula One) machine to compete against the powerful Japanese two-stroke GP bikes. The racing Beemer had engines originally designed to spin at 6000 rpm, yet Gietl made them reliable at 10,500. The BMW factory in Germany was already building BMW F750 racers to compete in the 1972 Imola 200 and the newly formed FIM F-750 class with riders Helmut Dahne, Dave Potter, and Hans-Otto Butenuth (Dahne finished 13th).

Chuck Dearborn on the first version of what would eventually morph into the Butler & Smith AMA Formula 750 bike. This one had a production frame. It would go on to become the early Reg Pridmore F750 machine. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

Chuck Dearborn on the first version of what would eventually morph into the Butler & Smith AMA Formula 750 bike. This one had a production frame. It would go on to become the early Reg Pridmore F750 machine. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

After initially using a modified production frame in the endurance iteration of the 750cc project, Gietl said it was the BMW factory frames that were used to develop the AMA Formula 750 racers.

Kurt Liebmann and John Potter began racing the BMW F-750 machine in 1972, in club events and select AMA National Road Races in the Junior class. In August of ’72 Liebmann won the Junior class at Pocono, giving the machine its biggest win ever.

The Formula 750 BMWs were then raced in the Daytona 200 in 1973 by Pridmore and Liebmann. There’s no question Daytona with its long straights and high-banked turns was not an ideal circuit for the BMW against massive horsepower of the bike 750cc two-stroke F-750 machines. To give you an idea of the speed disadvantage Liebmann and Pridmore faced, Paul Smart won the pole for the 200 that year on a Suzuki TR750 with an average speed of 101.871 mph hour. Liebmann and Pridmore qualified 74th and 75th respectively both at an average speed of just over 91 mph. Pridmore dropped out relatively early, while Liebmann finished the race four laps behind winner Yamaha’s Jarno Saarinen.

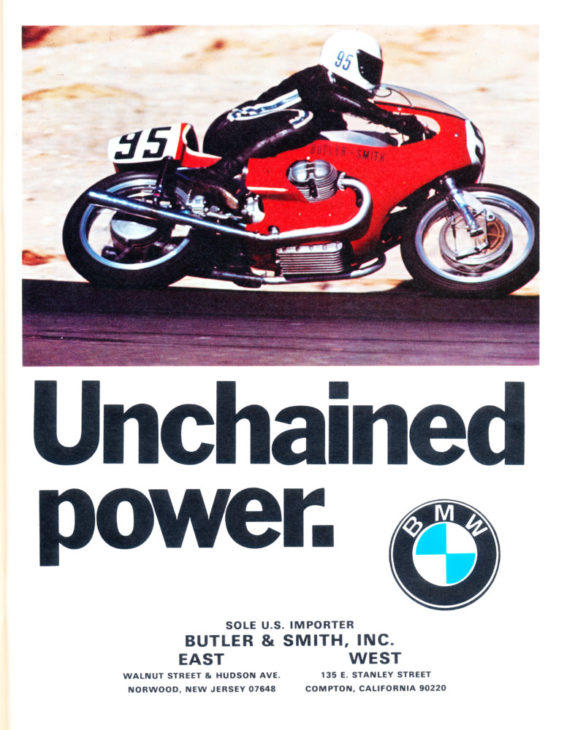

A mid-1970s BMW ad featuring Kurt Liebmann on the Butler & Smith R75/5-based Formula 750 motorcycle.

A mid-1970s BMW ad featuring Kurt Liebmann on the Butler & Smith R75/5-based Formula 750 motorcycle.

The tight and twisty Loudon, New Hampshire circuit was much better suited to the strengths of the BMW and Liebmann finished a respectable 13th, Pridmore 18th. Pridmore then gave the BMW F-750 racer its best finish of the season with an 11th-place at Pocono.

That would ultimately prove to be the best AMA Grand National result for the Butler & Smith F-750 machine, although Liebmann, Pridmore and Justus Taylor won numerous club races on the bikes.

The team continued to refine the bike and it improved over the next couple of seasons, but by now the Japanese two-strokes got better by leaps and bounds and had pretty much chased out nearly all of the four-stroke entries.

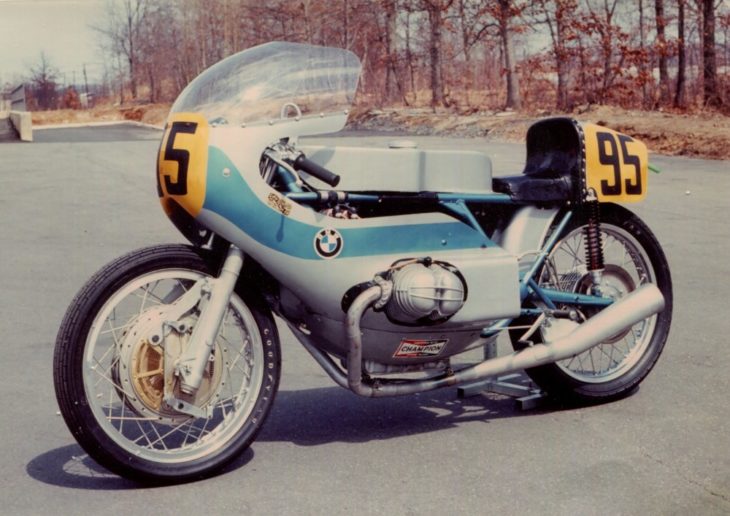

Kurt Liebmann won the Pocono AMA Junior class pro road race in 1972 on this version of the Butler & Smith F750 machine, which featured a factory Motorsport BMW frame. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

Kurt Liebmann won the Pocono AMA Junior class pro road race in 1972 on this version of the Butler & Smith F750 machine, which featured a factory Motorsport BMW frame. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl)

The BMW F-750 race bikes reached a peak of development in the project’s final season, 1975. The bikes were now revving to a stunning 10,500 rpm, producing 86 horsepower and capable of 165 mph. They were likely one of the most powerful pushrod twin motorcycle ever raced in AMA competition. That year Pridmore was pleasantly surprised to find that his machine was able to out accelerate even the mighty Yamaha TZ700s up the hill coming out of turn one at Road Atlanta, “As long as the TZs weren’t revved up to peak,” he added.

A more detailed look of the Butler & Smith BMW, which was housed in a factory Motorsport BMW frame. (Photo courtesy of Udo Gietl)

A more detailed look of the Butler & Smith BMW, which was housed in a factory Motorsport BMW frame. (Photo courtesy of Udo Gietl)

In order to produce that kind of power out of the mild-mannered R75 powerplant, Gietl was pushing the engine to its limits. “These were 50-mile motors,” Gietl grinned. “You’re not going to run an endurance race with these things. And you’d better rebuild them before the next race because the wear rate was quite high. The amount of flexing in the motor was pretty serious.”

Perhaps the biggest development of the last version of the BMW was the implementation of Rob North frames, which took place late in 1974. It was at Pridmore’s urging that the North frames were used. North had famously made excellent frames for factory Triumph and BSA Triples that finished 1-2-3 in the 1971 Daytona 200. The frames worked amazingly well.

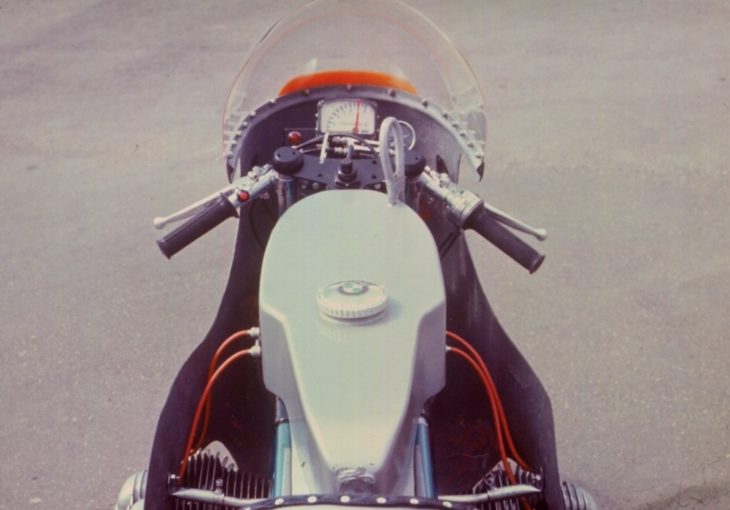

A look from the cockpit of the Butler & Smith BMW that won the Pocono Junior Road Race National with Kurt Liebmann at the controls. (Photo courtesy of Udo Gietl)

A look from the cockpit of the Butler & Smith BMW that won the Pocono Junior Road Race National with Kurt Liebmann at the controls. (Photo courtesy of Udo Gietl)

“Even with the cylinders sticking out with the North frame we could ride the bike to the edge of the tires without hitting anything,” Pridmore recalls. “It was an excellent handling machine, maybe 340 pounds and it flicked side to side very nicely.

At Daytona in ’75 Pridmore was having an excellent run. “I was right around the top 10 fairly late in the race when the bike broke,” he said.

Also, in 1975, Gary Fisher was recruited to race one of the B&S BMWs with a prototype monoshock and the new machine showed good speed in practice at Laguna Seca. During the race the monoshock broke, sidelining the bike. Fisher’s best result was 16th in the two-leg Ontario road race national at the end of the ’75 season.

Fisher’s Ontario finish marked the end of the BMW F-750 project. By then Butler & Smith was shifting focus to the up-and-coming AMA Superbike class and the excellent BMW R90S. Pridmore would win the 1976 AMA Superbike Championship on the Butler & Smith BMW R90S.

Justus Taylor racing the famous Butler & Smith BMW R75/5-based Formula 750 racer. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl.)

Justus Taylor racing the famous Butler & Smith BMW R75/5-based Formula 750 racer. (Photo courtesy Udo Gietl.)

The North-framed BMW F-750 bikes still survive according to Gietl. One he says one is at the Barber Museum and another at Irv Seaver BMW in Orange, California.

Gietl feels the F-750 BMW gave them the knowledge to put them at the top of the Superbike class in the early years.

Reg Pridmore’s gorgeous Butler & Smith BMW. Pridmore was the one who scored the highest placing in an AMA Grand National Road Race on the machine.

Reg Pridmore’s gorgeous Butler & Smith BMW. Pridmore was the one who scored the highest placing in an AMA Grand National Road Race on the machine.

“We learned so much from that Formula 750 bike that translated over,” Gietl said. “We put a lot of time and effort into that F-750 bike and we were proud of what we were able to get from the machine, but by then it was a lost cause with the domination of the two-strokes.”

Lost cause or not, the Butler & Smith Formula 750 machine was a motorcycle that began to change the staid image of BMW and its lasting legacy was helping to produce a championship-winning Superbike.