Alan Cathcart | September 21, 2018

A Brave New World

Moto2 is ditching the old Honda CBR600RR four-cylinder screamer for the growling snarl of Triumph’s Street Triple 765RS-based inline three-cylinder next year. Alan was one of the very select few to ride the prototype at Silverstone.

Alan Cathcart swoops around Silverstone’s Stowe circuit on the new 765. Moto2 will be very different in 2019!

Alan Cathcart swoops around Silverstone’s Stowe circuit on the new 765. Moto2 will be very different in 2019!

When the news broke 18 months ago that Triumph was set to replace Honda from 2019 onwards as the control-spec engine supplier for Moto2 with a specially tuned version of its then-brand new 765cc three-cylinder engine powering the all-new Street Triple, eyebrows were raised around the world, shortly followed by smiles.

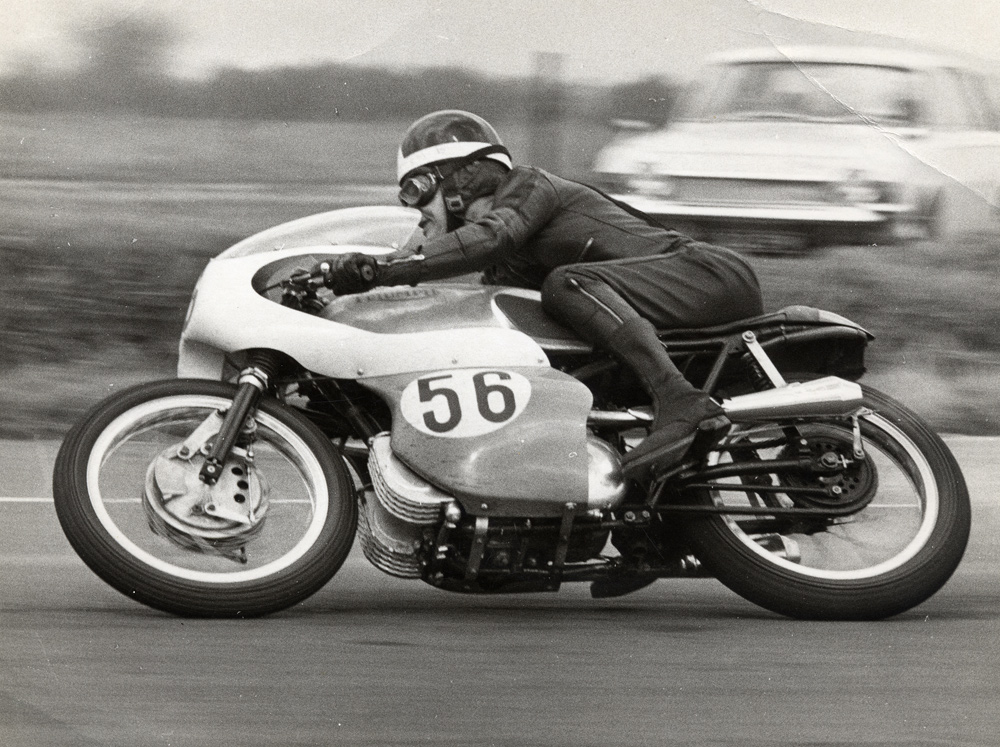

For the world’s joint oldest extant motorcycle marque, which built its first bikes in 1902 but hasn’t competed in Grand Prix racing since 1969, was finally making its way back to the MotoGP paddock—albeit as an engine supplier, rather than with its own factory-supported race team.

Photography by Kel Edge

And with the deal later cemented contractually in June 2017, it meant that from 2019 onwards the no-holds warfare that is Moto2 will play to a new soundtrack, with Honda’s high-revving four-cylinder 600cc screamers replaced by the glorious mellifluous howl of a herd of open-pipe three-cylinder racers. It’s a triple treat that hasn’t been heard on a GP racetrack for the best part of 50 years, ever since Giacomo Agostini last scored successive GP race victories and world title crowns on the three-cylinder 500cc/350cc MV Agustas in the early 1970s.

This totally unexpected three-year deal comprises the biggest shake up in GP racing’s intermediate class since Moto2 replaced 250GP two-strokes in 2010. For not only will the larger-capacity new Street Triple RS-based 765 motor be upwards of 10 horsepower more powerful than the outgoing Honda 600 four, as well as delivering lots more midrange torque, in 2019 for the first time the class will run traction control and clutchless downshift autoblippers, delivered via the Magneti Marelli control ECU that’ll be adopted in tandem with the three-cylinder Triumph engine. The arrangement will see the British manufacturer provide around 200 engines annually for the class, similar to what Honda has currently furnished for a full grid of 32-34 riders. That’s together with the supply of components to Dorna subsidiary ExternPro, based at Motorland Aragon in Spain, for them to refresh each motor after every three rounds in a current 19-race series.

This is very much a test mule, as the bike still uses a Daytona-derived chassis. The Moto2 race bikes will have bespoke chassis from the likes of NTS, Kalex, KTM, etc.

This is very much a test mule, as the bike still uses a Daytona-derived chassis. The Moto2 race bikes will have bespoke chassis from the likes of NTS, Kalex, KTM, etc.

Sealing The Deal

To be anointed as Dorna’s partner in taking the Moto2 category up a level in terms of performance and sophistication next season, Triumph had to overcome rival bids from several other manufacturers with established links to MotoGP—KTM, Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki are all believed to have tendered for the deal.

But it was the British manufacturer which clinched it, and Triumph’s R&D team has thus spent the past 18 months developing the engine, and evaluating the result on track mounted in a 2013 Daytona 675 test mule ridden by their designated R&D rider, 2009 125cc World Champion, Julián Simón, in a series of tests at Aragon and Calafat.

K-Tech has been heavily involved in the development of the test mule.

K-Tech has been heavily involved in the development of the test mule.

This June at Aragon the engines were finally matched for the first time on track with Magneti Marelli’s specially developed customisable control ECUs, and three key chassis manufacturers (Kalex, KTM and NTS) ran the Triumph engine for the first time in their prototype 2019 frames, evaluating the 765cc powerplant in near-race conditions. That left the Daytona test mule fitted with Triumph’s stock Keihin ECU off the Street Triple 765 surplus to requirements, so what better than to expose it to a group of journalists and ex-racers now working as TV commentators by letting us loose aboard it at Silverstone’s short 1.08-mile Stowe circuit? Thus, we could sample the fruits of Triumph chief engineer Stuart Wood and his R&D team’s efforts in producing a mechanical gamechanger for the Moto2 category from next year onwards.

This dash should be familiar to any Triumph riders.

This dash should be familiar to any Triumph riders.

Riding The Future

The Moto2 engine’s improvement in performance was very quickly apparent during my quarter of an hour spent riding the test bike fitted with a Street Triple RS Keihin ECU, dash and quickshifter—but no autoblipper yet—and with its ABS and traction control disabled, on the short but just about adequately quick Stowe circuit, where a true fourth gear is the best you’ll get.

However, that was sufficient to appreciate the tuned-up Triumph’s inherent qualities—starting with the one thing you’re aware of first, last and always when riding this bike, especially without earplugs, and that’s the glorious, haunting howl from the Arrow pipe that’s devoid of any silencing.

Imagine how good 30 un-muffled triples are going to sound like!

Imagine how good 30 un-muffled triples are going to sound like!

I’m fortunate to have ridden several classic MV triples, as well as the Chaz Davies Supersport 675 which was quite stirring to ride in terms of the engine note, mainly because of the intake roar you got even with an airbox fitted, but that wore a silencer to meet WSBK noise limits. Whereas like the MV Agustas, the Moto2 Triumph’s exhaust is free to air and all the better for it. When the lights go out for Moto2’s first race of the Triumph era, the sound of 30-plus open-piped triples surging down to the first turn will be worth the ticket price alone!

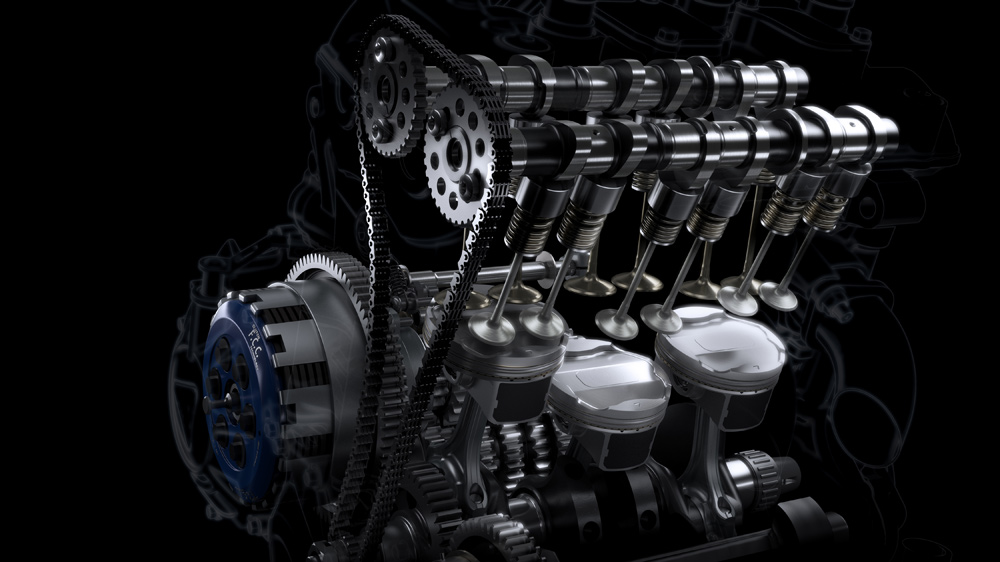

The standard crankshaft, counterbalancer, conrods and cast three-ring pistons are all retained in unmodified form on the race engine.

The standard crankshaft, counterbalancer, conrods and cast three-ring pistons are all retained in unmodified form on the race engine.

But there are no prizes for sounding great, so where the 765 motor really delivers is the strong hit and broad spread of midrange torque, coupled with the smooth pull out of second-gear turns, of which there are several on the Stowe circuit. It’s more of a souped-up street bike you could go to the shops on very quickly than a gnarly, peaky GP racer.

Throttle pickup on the ride-by-wire system is ideally controlled, with no jerkiness to get the rear Dunlop Moto2 control slick spinning in the absence of traction control, just a smooth but relentless drive out of the bend as you ride what feels like a substantially fatter torque curve, and flat-shift wide open down to the next turn.

To begin with I had to remind myself to use all the revs that this meaty, muscular, middleweight motor is so eager to deliver, with the row of blue lights across the top of the dash building in number en-route to the 14,000 rpm rev limit. The fact I could only see the upper numbers on the analogue tacho thanks to Triumph’s PR team sticking a GoPro camera directly in front of it, didn’t help but after a couple of laps I’d programmed my mind to cut down on the gearshifts and rev it right out on the two short straights. I was rewarded with the kind of vivid acceleration a factory one-litre Superbike delivered only a handful of years ago, as the Moto2 Triumph boasting a similar power-to-weight ratio howled its way down the track, revs shooting to that fourteen-grand rev limit almost instantaneously. Phew! This is fun.

Having now started to exploit the extra power available at higher revs, I thought I should try to start using that longer first gear in a couple of the slower turns. Mistake. Apart from saving two unnecessary gearshifts by sticking in second, the peakier top-end performance had the front wheel lifting after I’d pulled the Triumph upright from full lean and pinned the throttle wide open. Better to surf that fat, flat torque curve and drive cleanly away from the bend from around 8,000 rpm upwards—not exactly low down the rev scale by street bike standards, but lower midrange on a Moto2 GP racer like this one.

Triumph last competed in Grand Prix racing when factory tester Percy Tait (seen here at Thruxton) finished second to Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta triple on his 500 Daytona twin in the 1969 500cc Belgian GP run on the ultra-fast Spa-Francorchamps circuit. He was the only rider not to be lapped by the Italian world champion!

Triumph last competed in Grand Prix racing when factory tester Percy Tait (seen here at Thruxton) finished second to Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta triple on his 500 Daytona twin in the 1969 500cc Belgian GP run on the ultra-fast Spa-Francorchamps circuit. He was the only rider not to be lapped by the Italian world champion!

Just Like A 250

Equipped with K-Tech race suspension front and rear, this Daytona-chassised junior superbike steered like an old-school 250GP racer on steroids, with agile handling thanks to its slim build occasioned by the narrow three-cylinder engine. I do feel the Triumph to be a little taller than the innumerable Honda 600 Supersports I’ve ridden down the years, so presumably current Moto2 riders will notice the same when they switch to their new-generation triples. The Triumph engine’s narrower build will surely result in Kalex & Co. producing radically different frames compared to their current 600cc four-cylinder packages, resulting in even more nimble packages. Will this result in Kalex’s current domination of Moto2 grids being challenged? Let’s wait and see.

More K-Tech goodness with their specially developed shock.

More K-Tech goodness with their specially developed shock.

Though I really missed the absent autoblipper that’s now become second nature when riding a modern sportbike on a racetrack, which meant I had to use the clutch when downshifting under braking, the Triumph stopped well thanks to the excellent Nissin radial front brakes, and a fair bit of engine braking left dialed in to the slipper clutch setup. Yet it was totally stable driving hard through the only fast third-gear turn on the Stowe circuit. Nice, but it left me thirsting for more—more distance on the racetrack to get a better idea of how the engine will perform at higher speeds on a faster circuit, and more time on this totally addictive motorcycle with that great-sounding and ultra-responsive motor.

The compression has been raised to 14:1 from 12.65:1 on the stock RS by skimming the head, with a lighter, low output race alternator used to reduce inertia.

The compression has been raised to 14:1 from 12.65:1 on the stock RS by skimming the head, with a lighter, low output race alternator used to reduce inertia.

For this brief hands-on introduction to Triumph’s Moto2 R&D was all about the engine, and you can’t help but relish its linear drive all through the powerband, with no layers in the powerband as their Supersport 675 once suffered from before being refined into an Isle of Man TT-winning, BSB Supersport Champion, and WorldSSP rostrum finisher. The Moto2 Triumph 765 has a well-rounded power delivery with a fatter hit of midrange torque compared to a comparable four, and its trump card versus the Honda 600 it replaces will be its acceleration out of turns, aided by that addictive rush of grunt—it feels smooth and refined in its engine response, especially in terms of pickup from a closed throttle. The Triumph is basically the best of both worlds. It pulls like a twin from low down, but revs like a four up high. However, you must force yourself to use a gear higher than often seems appropriate in lots of turns, which allowed me to hold second gear all through the Stowe circuit’s final complex of tight turns, working on and off the throttle.

Riding this work-in-progress prototype felt good—but the nature of the track Triumph had chosen for this brief test meant this was all about demonstrating the mechanical attributes of their tuned-up 765RS engine, rather than exploiting the handling—and the absence of the Marelli ECU made this a snapshot of a certain stage in the development of that motor.

I can’t wait to ride one of the Triumph-engined Moto2 racers further down the R&D line, fitted with the full Marelli race ECU, to get a better picture of how good the complete package will be, but this taster test proved very enticing. Oh, and please, Triumph—build that Daytona 765!

This test was a teaser, the real acid test comes when the motor is fitted to a real race chassis.

This test was a teaser, the real acid test comes when the motor is fitted to a real race chassis.

Triumph’s Racing Philosophy

Headed by one-time HRC race engineer (and Nicky Hayden’s former crew chief) Trevor Morris, ExternPro took over Moto2 engine preparation at the end of the 2012 season, and will be responsible for supplying a new or reconditioned Triumph Moto2 powerplant to each rider. The Honda engines used currently are reconditioned every three GP races with a new crankshaft, pistons and rods, then re-allocated via a lottery system. All engines are numbered, with a detailed record available for each, and they’re each sealed in four places to ensure that teams can’t make their own internal modifications.

Steve Sargent has been charged with leading the Triumph’s development in race guise.

Steve Sargent has been charged with leading the Triumph’s development in race guise.

ExternPro’s contract with Dorna and the FIM allows a three percent variation in peak power of just under 130 bhp for the CBR motors—but the company’s attention to detail has helped them reduce that difference to around one percent. That’ll be their target with the Triumph engines, too!

As the Triumph executive in charge of the project, Chief Product Manager Steve Sargent (who we will have a separate interview with in a later issue if Cycle News), confirms, this move is an ideal entry into MotoGP racing for Triumph, delivering an important presence at the highest level to the British firm.

“I think the big benefit for Triumph is obviously in terms of exposure, and also the demonstration of [our] engineering capability,” he says. “We’ll be getting the Triumph name out there to an audience that might be less familiar with the brand, and our products.”

Some commentators have stamped this move as a surprise on the grounds that Triumph is supposedly anti-racing—somewhat unreasonably, given that it’s already competed in the WorldSSP series with world champion (on a Yamaha) and today’s WorldSBK star Chaz Davies, who scored four rostrum finishes on his 675 Daytona en-route to fourth in the championship in 2010.

As company owner John Bloor told me in a personal interview some years ago, he supports racing when it can be beneficial to Triumph’s street bikes.

The Triumph brand has recent history in world racing, having competed his success with Chaz Davies in WorldSSP.

The Triumph brand has recent history in world racing, having competed his success with Chaz Davies in WorldSSP.

“We’re interested in racing—we don’t rule anything out that might be a benefit to improving the product,” Bloor said. “I go to Donington Park every year, I’ve been to Assen to watch, I’ve been to Daytona—it’s totally incorrect for people to say I hate racing, because it’s quite the opposite. It’s just that in the early days when we were building things up, I didn’t want to dilute the effort—try to do everything, and you’ll make a good job of nothing.

“Our main objective as a company is to get the street product right, and if racing can help that, we’ll do it.”

The emphasis placed by Dorna on reliability above all else for Triumph’s Moto2 engines when stressed out in the white heat of competition will surely benefit 765 streetbike customers—let alone lead to the surely inevitable development in due course of a race replica sportbike incorporating the performance enhancements to the RS version of the engine, which would be an exciting middleweight rival to, say, the Suzuki GSX-R750.

Despite this, Sargent insists there are no plans yet to produce such a bike.

“We keep being asked if we’re going to do a Daytona 765 street version using the same engine tune,” he says, “but fundamentally we’ve always said that, if there’s enough demand for one, then we’ll consider doing it!”

After axing the Daytona 675 for 2017 when the 765cc engine made its debut, Triumph may already be preparing the ground for the (re-)introduction of such a bike “by popular demand.”

This is still a Daytona chassis under the bodywork, but obvious clues like the gigantic radiator hint at a more serious purpose.

This is still a Daytona chassis under the bodywork, but obvious clues like the gigantic radiator hint at a more serious purpose.

Making the 765 Into A GP Racer

Stuart Wood’s technical marvel retained all the stock 765 engine castings, including the Nikasil-lined cylinder block, and modified the internals—though rather surprisingly not as much as you might expect. “We’d agreed with Dorna to use our new larger-capacity 765cc three-cylinder motor rather than the old 675, and we knew what we wanted to do with it, which was obviously to get more power and more torque out of the engine compared to the standard street bike,” says Steve Sargent. “To do that, we needed to spin the engine up faster, and to reduce the inertia within it.” This entailed removing superfluous items like the starter motor, then comprehensively re-porting and gas-flowing the cylinder head to allow the engine to breathe better.

The stock offset chain drive to the cams has been retained, with max revs punched out to 14,000 rpm.

The stock offset chain drive to the cams has been retained, with max revs punched out to 14,000 rpm.

They fitted lighter titanium valves the same size as on the 765RS street engine, but with stiffer valve springs, and race camshafts with higher lift and greater duration on the valve timing. The shape of the combustion chamber is essentially unchanged, but compression has been raised to 14:1 from 12.65:1 on the stock RS by skimming the head, with a lighter, low output race alternator which Sargent says makes a big difference in reducing inertia. There are revised engine covers to reduce the engine’s width, as well as a different cast alloy engine sump to permit a more tucked in run for the 3-1 Arrow titanium exhaust’s headers.

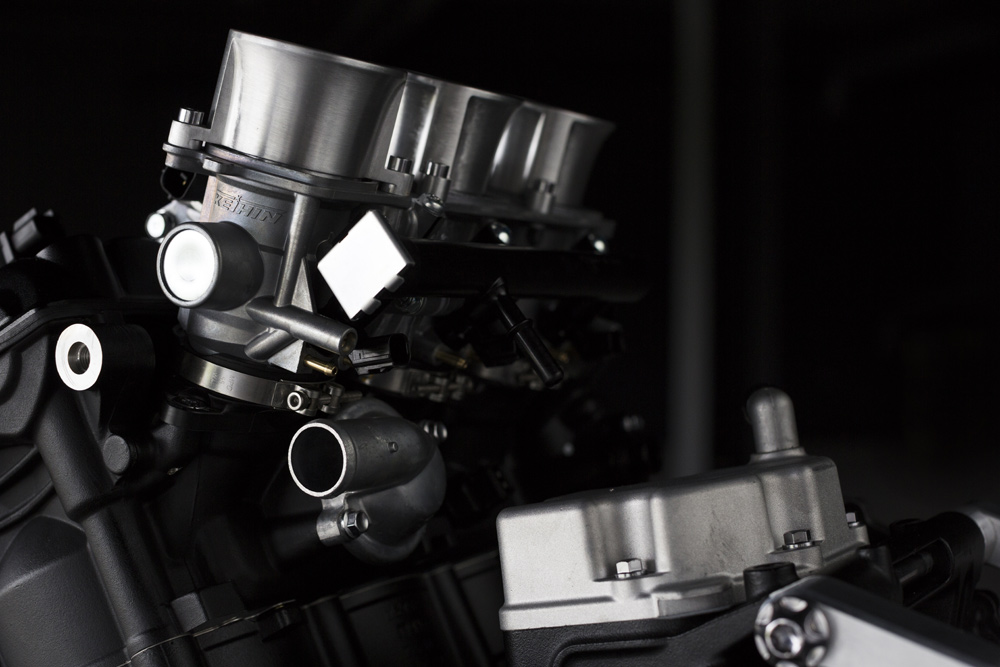

Keihin throttle bodies will be exclusively used on the Moto2 engine.

Keihin throttle bodies will be exclusively used on the Moto2 engine.

The standard crankshaft, counterbalancer, conrods and cast three-ring pistons are all retained in unmodified form—so the crank hasn’t been lightened—but a close-ratio six-speed gearbox has been created by fitting a taller ratio first gear and slightly shorter second gear, while retaining the same upper four ratios in the 765RS street bike transmission. It’s worth noting that Moto2 teams aren’t allowed to change the internal ratios of the gearbox, nor the primary drive, which is also standard on the Triumph motor, but the race-developed slipper clutch now fitted is tuneable.

The stock offset chain drive to the cams has been retained, rather than gears, and the rev ceiling’s been raised from 12,650 rpm on the road bike, to 14,000 rpm—an impressive demonstration of the robustness of the 765 Street Triple engine.

“It’s an engine that we know very well, because the fundamentals of the design remain the same as the Daytona 675 that came out in 2006,” says Sargent. “So, we do know the engine very well, and in terms of understanding what we needed to do to it to provide adequate performance, it meant doing things that we pretty much knew already anyway.”

Davies’ smaller capacity WorldSSP motor pumped out a massive 144 hp in race trim, 14 hp more than what Triumph is claiming for the Moto2 engine.

Davies’ smaller capacity WorldSSP motor pumped out a massive 144 hp in race trim, 14 hp more than what Triumph is claiming for the Moto2 engine.

The result delivers what Sargent confines himself to stating is “over 135 horsepower” at 14,000 rpm versus the street 765RS’s 123 horsepower at 11,700 revs, with 59 lb-ft of torque at 13,500 rpm versus 56.7 lb-ft at 10,800 rpm on the RS. But whereas the 765RS figures are taken at the crankshaft, Sargent declares the Moto2 readings to be taken at the gearbox i.e. on a dyno (however, Chaz Davies’s smaller capacity 675 Supersport revved as high as 15,500 rpm and produced 144 bhp at the rear wheel, so there’s surely room for development).CN

| SPECIFICATIONS |

Triumph Moto2 Prototype |

| Engine: |

Water-cooled DOHC 12-valve transverse in-line 3-cylinder 4-stroke with offset chain camshaft drive and 120-degree crankshaft |

| Bore and stroke: |

78 x 53.4mm |

| Capacity: |

765cc |

| Max power: |

Over 135 bhp at 14,000 rpm (at gearbox) |

| Max torque: |

59 lb-ft at 13,500 rpm (at gearbox) |

| Compression ratio: |

14:01 |

| Engine management (as tested): |

Multipoint sequential Keihin electronic fuel injection with 3 x 44mm throttle bodies, RBW digital throttle, and single injector per cylinder (Magneti Marelli ECU for racing) |

| Gearbox: |

6-speed with quickshifter |

| Clutch: |

Multiplate oil-bath slipper clutch |

| Chassis: |

Gravity-diecast aluminum twin-spar frame |

| Front suspension: |

43mm K-Tech inverted telescopic forks with fully adjustable pressurized gas cartridge internals |

| Rear suspension: |

Gravity-diecast aluminum swingarm with fully adjustable K-Tech shock and progressive rate link |

| Front brakes: |

Front: Dual 310mm steel discs with 4-piston Nissin radial calipers |

| Rear brakes: |

Single 220mm steel disc with 1-piston Nissin caliper |

| Rake: |

23.5° |

| Trail: |

3.41 in. |

| Wheelbase: |

55.1 in. |

| Weight: |

341 lbs. with oil and water, no fuel |

| Weight distribution: |

51/49 percent static |

| Front tire and wheel: |

120/70-17 Dunlop Moto2. 3.50 in OZ forged aluminum wheel |

| Rear tire and wheel: |

195/75-17 Dunlop Moto2. 5.50 in. OZ forged aluminum wheel |

Click here for all the latest MotoGP news.