Michael Scott | August 3, 2018

The Beautiful Sport

COLUMN

As the faint afterglow of the soccer World Cup in Russia dies away, there are still some truths to be gleaned from the embers. They have to do with sport, scoreboards, and the essence of purity.

We all love motorcycle racing. It has athleticism, non-stop potential for all sorts of surprises, and also quite a lot of hectic action. Not to mention interesting engines and absorbing technology. But I have personally never warmed to what footie fans are wont (nay, determined) to call “The Beautiful Game.”

Oh, I can see the artistry of ball control, the agility of the footwork, the tactical teamwork. I can also see the passion of the fans, often at boiling point or beyond.

But I think the main problem is that the all-important potential for surprises is so very seldom fulfilled. It’s the long, drawn-out one-all games that are a real turn-off. Worse still, the no-score draws. Lots of seemingly pointless running around and kicking the ball about, all for nothing. Then an anti-climax: after what now feels like many hours of unrewarded skill and artistry, the result is decided by the random good or bad luck of a penalty shootout.

For some reason, the recent soccer series in Russia did stimulate a wider interest than usual, for me and many others. And it was while watching one or another game in one or another public house that I wondered out loud: wouldn’t it be better if they could get some scores on the board? It is clearly very difficult ever to score a goal. Why not make it easier?

Why don’t they simply make the goals a bit wider?

This suggestion was howled down by the real fans. Apparently I’d missed the point. In the same way that the players were missing the goal mouth. Such a change would destroy the purity of The Beautiful Game.

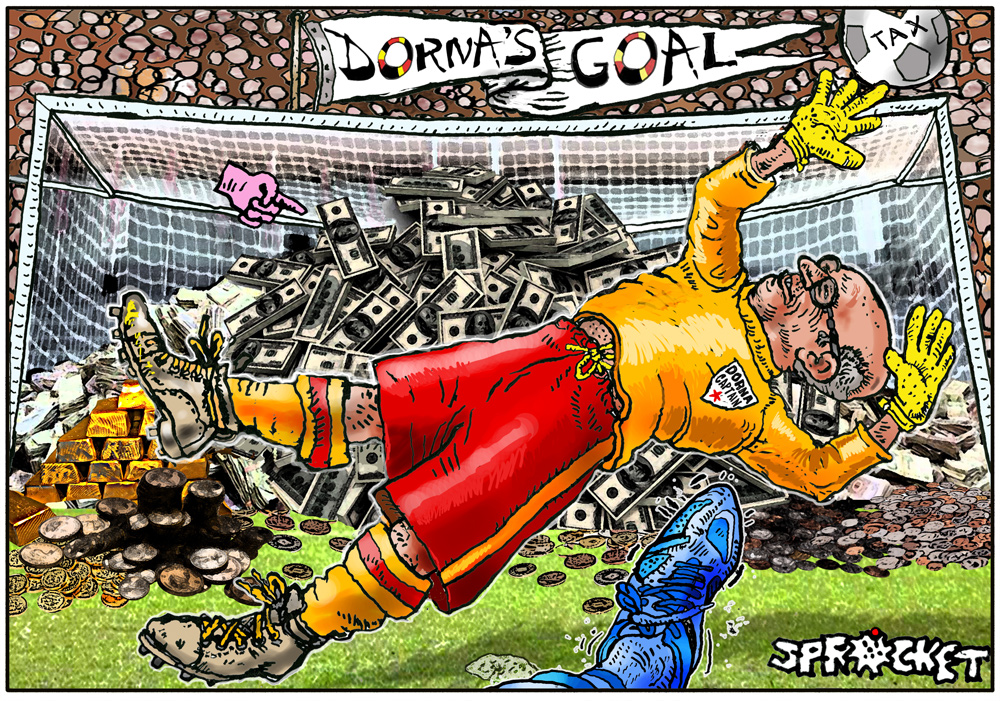

It came to me, while I was on the way home a bit later: this is effectively what Dorna has done. The continuing MotoGP dumb-down drive, applied with steady pressure over the past five years, has made the goal mouth wider.

All the bikes have become more similar to one another, with the number of cylinders and the maximum bore size prescribed, leveling their performance, to a degree. At the same time, as electronics have become exponentially more sophisticated and useful, they have also become less sophisticated, in terms of control hardware and software. One size fits all, and an area of individual team/rider specialization has been nullified.

In a nutshell, although the limit keeps getting faster as technology develops, it has also become easier and safer to attain.

Repsol Honda recently released a surprisingly un-cheesy video, using trick photography, of Dani Pedrosa interviewing himself. As an interviewer and an interviewee, he is a very good rider, but one insight struck home.

“Before,” he told himself, “it was easy to see the potential of a rider, with the two-strokes. Now, with the four-strokes, I find it hard to figure out who is a good rider.”

This is the consequence of making the limit easier to find.

The question is this: has it damaged the purity of the sport?

It’s actually harder to answer than you might imagine.

In one way, yes. It is of course far from easy to get the most out of a bronco with well over 250 horsepower, but the way is open to more people than ever before. The exam is simpler, and the number of people passing with distinction therefore larger.

In another way, hell no.

Just look at what happened at Assen this year. A record close top 15 was one thing, but more to the point was how large was the group contesting victory, how much it changed every lap (somebody claimed to have counted more than 200 overtakes, though I’m not quite sure how they managed that), and what a thrill it was to watch these massively fast motorcycles trading blows with as much ferocity as one expects in relatively gutless Moto3.

When Marquez rose above the brawl, leaving the rest tripping over one another, it was very revealing about the level of his talent.

This confirms an old truth about bike racing: that no matter what else changes, the same people tend to win. There was a record nine different race winners in 2016, but that was an exception. Last year, it was more normalized, with five different winners, and Marquez and Dovizioso each taking a third of them, six out of 18.

So far this year, four different winners in the first nine races, one each for Dovizioso and Crutchlow, two for Lorenzo, and the remaining five for Marquez.

So if the same person wins, but the fans have more fun, is MotoGP still The Beautiful Sport? CN