Michael Scott | July 4, 2018

Talent Versus the Poverty Gap

COLUMN

Questions asked at parties, number nine: “Do bike grand prix racers get paid millions like F1 drivers?” My reply’s been the same for years.

Racing is like rock music. Those who make it big make it very big. Riches beyond avarice. Think Rolling Stones. Or the rolling Stoner—in spite of his, Casey Stoner’s early retirement aged just 27. (A rather different kind of “27 Club” from that in pop.)

But there are hordes of superbly talented musicians who end up starving in lonely garrets. Or doing the dish washing. Talent by itself is not enough.

It’s even more the case—even less room at the top—in bike racing. In spite of successful commercialization, and in spite of the continuing redistribution of wealth initiated by IRTA in the 1990s (currently aimed at giving independent teams financial stability), there are many, many more good riders struggling to make ends meet than there are buying luxury homes in Andorra.

Oh boy, it’s not as bad as it used to be. I recall talking in the paddock in Austria to South African rider Mario Rademeyer, a privateer 250 podium finisher in the mid-1980s. He was describing his struggle, in his ripe accent. “You know when bread goes green and you throw it away?” “Well, we ate it.” Eventually 250 champ Christian Sarron saw him rummaging in the dustbins at suppertime, took pity and helped supplement his diet.

He was far from the only impecunious racer. In the even older days, riders had to earn their keep in non-championship races that paid relatively decent money—often highly dangerous affairs run on public roads. That would buy enough fuel to get to the next GP, although even then it was a gamble whether your entry would be accepted.

But the Rademeyer plaint was in a different era. By now, the new teams’ association IRTA was flexing its youthful muscles and picking the fat cats’ pockets on behalf of its members. Even more significantly, a phalanx of tobacco sponsors—increasingly denied the chance to spend their ill-gotten gains on advertising by spreading international legislative bans—were flooding GP racing with great pots of money. It was the start of high-end paddock living, with chefs and fancy food for the big teams, mouldy green crusts for others. It didn’t get past the guys at the top. Still doesn’t.

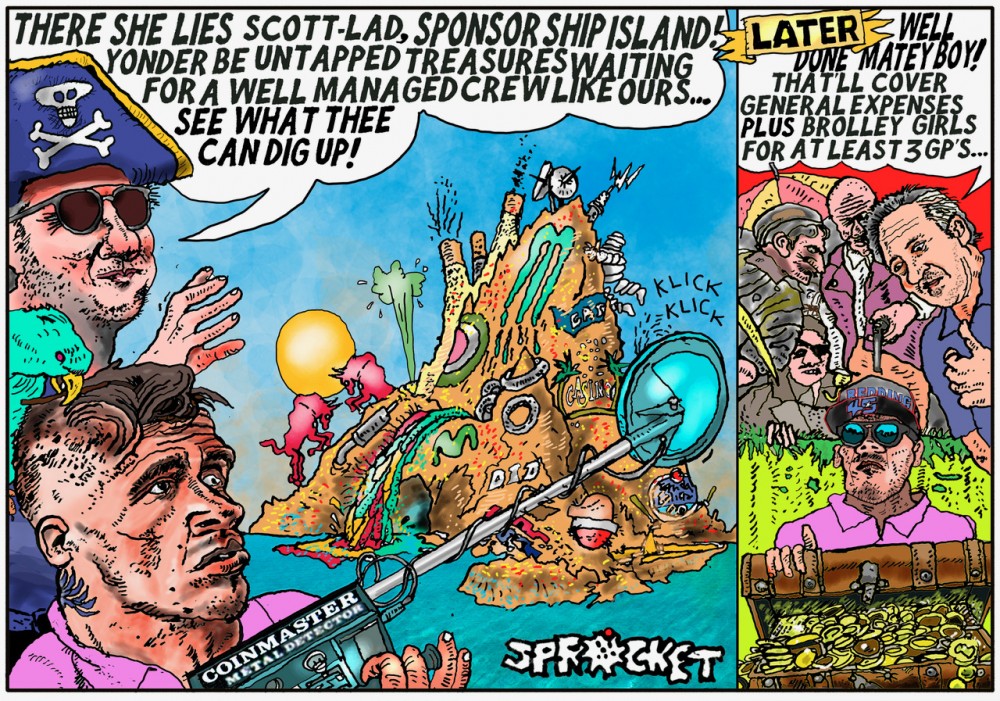

Consider the plight of Scott Redding. Good enough to win GPs (still the youngest ever to do so) and challenge for the Moto2 title. But sadly not good enough to keep his MotoGP ride. He’s due for the chop after battling along on a second-rate Honda, then a Ducati and now Aprilia. None of this made him enough to pay for early retirement, but unless he can find a sponsor to buy him a seat. Maybe in Superbikes or back in Moto2, that is what he is facing. Being fast hasn’t made him rich.

There’s a lot more like him, coming from 10th to last, in all three classes. The gap between their talent and the winners’ is very narrow, sometimes (like in the rain) imperceptibly so. The gap in prosperity is staggeringly large.

Another for-instance: Jorge Lorenzo, 12-million Euros a year. Xavier Simeon—minus at least one million Euros a year, the cost of his MotoGP ride. Maybe the Belgian isn’t a good example. He’s won only a single Moto2 GP, and was never a shining light, but has good backing as the only Belgian in the business. But it’s rumored that Thomas Luthi’s ride with the controversial Marc VDS team cost him the same. He is a former 125 World Champion, and another serious race-winning Moto2 talent.

Level notwithstanding, it’s pretty normal, especially in the smaller classes, to have to buy your ride. Motos 2 and 3 are full of examples, though the number of zeros behind the cost is not as large. Just this weekend came the news that the first Kazakhstani rider in the series, 19-year-old Makar Yurchenko, has been dropped by his French CIP/KTM team because promised sponsorship payment didn’t materialize. Never mind that he’d made it into the points three times in the last four races.

It gets worse. For all these unfortunates, the bikes they are paying for aren’t really up to much either. Which is why it’s so hard to break the circle, and why they generally pray for rain to level the chances.

We in the press are guilty of reinforcing this status quo. It’s the big stars who get the ink. But to be fair it’s not only because they have better PR organizations and more press releases. The fans are interested because they’re winning. So it’s your fault, too.

Now and then, though, spare a thought for those who—often through little fault of their own—aren’t.CN