Michael Scott | March 9, 2018

Is this a second golden age of MotoGP racing? The new MotoGP season—at 19 rounds the longest ever—begins on March 18, and after eight months of racing the fans, and the 24 riders in the premier class, will provide the answer.

Marc Marquez is the odds-on favorite to win 2018, but this is MotoGP, and anything can happen!

Marc Marquez is the odds-on favorite to win 2018, but this is MotoGP, and anything can happen!

MotoGP 2018 Season Preview—The New Golden Age

2018 comes off the back of two epic years. In 2016, there were a record nine different race winners. This showed that Dorna’s dumbed-down technical restrictions really did level the odds, and cut the factory teams down to size.

In 2017, there were fewer winners—just five. But the battle for overall victory between defending champion Marc Marquez and veteran Andrea Dovizioso on the reinvigorated Ducati was only resolved at the final race. The pre-eminent pair shared six wins apiece. Three more went to Maverick Vinales, one to Movistar Yamaha teammate Valentino Rossi, and two to Marquez’s Repsol Honda stalwart Dani Pedrosa.

The crown went, as we know, to Marquez, his fourth in five years on the factory Honda, confirming his status as the dominant force of modern racing. But, thanks to some miscalculations at Honda combined with Dorna’s rule freezing engine development throughout the season, it was an uphill struggle and a classic example of genius turning hubris into victory.

Dovizioso is back with a faster bike for this year. Can he finally wrestle a MotoGP title away from Marquez?

Dovizioso is back with a faster bike for this year. Can he finally wrestle a MotoGP title away from Marquez?

The roots of Marquez’s difficulties were nourished by HRC’s sometimes fruitful but often pig-headed determination to do things their own way. While rivals prepared for the unified hardware of 2014, then unified software in 2016, HRC persisted with their own highly sophisticated in-house electronics until the last possible moment. Yamaha and Ducati were already familiar with the Magneti Marelli systems and techniques, Honda had to learn from scratch. It proved complicated.

Another dimension came from the freeze in engine changes. In 2015, Honda installed a low-inertia crankshaft, giving very jagged throttle response and spoiling acceleration. The next year, they reversed crankshaft rotation, and the revised torque reaction upset everything they knew about chassis behavior. And in 2017, another major change—different firing intervals with a more Big Bang effect.

In all cases, they were stuck with it, giving riders a whole new set of parameters to master.

He may have a two-year-old bike, but Zarco has been hauling butt in testing so far.

He may have a two-year-old bike, but Zarco has been hauling butt in testing so far.

In 2015, a flummoxed Marquez was third overall to the Yamahas, but over the next two years, his skill and determination prevailed. Hugely helped by a willingness to have many crashes—17 in 2016 and 27 last year. He had to fight hard for both of those titles.

Last year, by mid-season, he had managed just two wins and had crashed out twice. After that, he and his engineers finally getting to grips with the bike’s latest quirks, it still took him until the 18th and final race before he was confirmed champion for the fourth time.

For 2018, pre-season tests have sounded an ominous note for the opposition. This year’s Honda appears to have fewer built-in quirks and a significant power boost. Instead of struggling and crashing, Marquez and Pedrosa have made smooth and very rapid progress.

Aleix Espargaro has a new bike and teammate at Aprilia and will be looking to finally grab a podium for the Noale team in MotoGP.

Aleix Espargaro has a new bike and teammate at Aprilia and will be looking to finally grab a podium for the Noale team in MotoGP.

Last year’s opposition was from Ducati, where, in its fifth year under ex-Aprilia engineer Gigi Dall’Igna, the Italians had done the opposite of Honda—at last finding a way to harness their desmodromic engine’s class-leading horsepower in a chassis that was able to find its way around corners better than ever. For the first time since winning with Casey Stoner in 2008, in the experienced hands of Andrea Dovizioso, Ducati was a serious title threat.

He was helped by a switch (by popular demand) to a harder front tire construction, leading directly to his first win of the year at Mugello. Twice he out-braved Marquez in last-corner shoot-outs, but the Ducati still struggled at tracks where sustained turning momentum was required, like Phillip Island, where a lowly 13th place lost him the championship.

New teammate Jorge Lorenzo proved a fast learner and made the podium three times; satellite rider Danilo Petrucci (on a factory bike in Pramac colors) got four.

Rossi is back for another crack at a 10th World Championship but will be up against it this season.

Rossi is back for another crack at a 10th World Championship but will be up against it this season.

Further improvements were obvious at this year’s pre-season tests, and Lorenzo topped the time-sheets at the first Sepang outing. More impressively, new Pramac recruit Jack Miller, on a 2017 bike, was right up with the fastest guys.

The question that needs answering concerns race pace and consistency over different tracks. Only if the Duke is strong here can it pose a serious challenge to the mighty Hondas.

And Yamaha? Last year, the traditional Honda rival stumbled. New recruit Maverick Vinales had dominated the tests and took the first two races, but took only one more win; Movistar teammate Valentino Rossi also won only once; while class rookie Johann Zarco (up from winning the first double Moto2 crown) made hay on the 2016 bike.

A winter of development was based on the 2016 chassis. But the early tests were not too promising. The factory riders both had problems with sustained runs, and (as last year) were complaining of different issues, adding to further confusion.

Jack Miller has taken to the Ducati like a duck to water. The Australian will surely be in for a podium shot this year.

Jack Miller has taken to the Ducati like a duck to water. The Australian will surely be in for a podium shot this year.

And all the while Johann Zarco, who had elected to retain his 2016 bike, was going consistently fast. The Frenchman underlined his strength by posting the top time at the final tests at Qatar.

Alex Rins’s first year at Suzuki was spoiled by several injuries: his second started in flying style when he placed fifth at Buriram (Thailand) tests and eighth at Qatar. The factory has reverted to “concession” status after poor results last year, meaning extra tests and free engine development. The GSX-RR chassis already boasts sweet handling, and the Japanese poor relation could pack some surprises. At the same time, hot property Rins might inspire his erratic team-mate Andrea Iannone to greater feats in his own second year. The Italian was fastest on day two at Qatar.

Franco Morbidelli moves up from Moto2 as champion and will have more than a few eyes on his progress after fellow Moto2 champion Johann Zarco’s incredible performances last year.

Franco Morbidelli moves up from Moto2 as champion and will have more than a few eyes on his progress after fellow Moto2 champion Johann Zarco’s incredible performances last year.

Aprilia and KTM remain as concession teams, with a different status. The Italian squad retained hard charger Aleix Espargaro and recruited the so-far disappointing Scott Redding, and has furnished them with a new engine. Aprilia has plenty to prove.

So too KTM, after a very strong debut 2017. Pol Espargaro and Bradley Smith are staying on, with test rider Mika Kallio promised the odd wildcard outing. If the Austrian bikes—with their heretical steel-tube frames and WP suspension—continue to improve at the same rate, they could attract stronger riders for next season.

Racing starts in Qatar on March 18 and spans the globe (including a new round at Buriram) before finishing as is now traditional at Valencia on November 18.

Place your bets. My money is going on Marquez. But with the Michelin control tires again adding a variable, it could be more open than it at first appears.

The Title Contenders

Marc Marquez

Youngest-ever champ at 21, Marquez won four of the last five titles, the last two without much help from the bike. He is a super-talent who is already easily the greatest of his generation. Now 25, he has a better bike, plus experience and enough maturity to cut the crash rate. Watch him go.

Andrea Dovizioso

Dovi surprised everybody last year, adding well-timed aggression without betraying his careful and mature riding technique. The wins should strengthen his hand still further, and if his Ducati also comes back stronger, who knows what he can achieve.

Maverick Vinales

Last year’s test form and early races suggested a runaway win for the fancied Spaniard. A slow start this year, but what changed for the worse last year might do the opposite in 2018. Maverick does seem to get thrown off the scent rather easily, but there’s no doubting his talent.

Dani Pedrosa

Will 2018 finally be Dani’s moment? Vastly experienced and a race winner every year since joining MotoGP in 2006, the former 125 and double 250 champion has been always the bridesmaid. Teammate Marquez will keep him there. But if anything happens to Marc…

The Dark Horses

Johann Zarco

By the end of last year, the double Moto2 champ was more than a rostrum threat. He nearly won in Valencia. Now he topped the timesheets in the final test. He’s smooth, stylish, clever, and much faster than a non-factory rider is expected to be.

Valentino Rossi

Now almost 40, can one take Rossi seriously as a title contender? Ask it the other way around, and, as always, only a fool rules Rossi out. He’s not as fast as he once was, but he’s at least as clever. If the odds move even slightly in his favor, he will play them to the max.

Jorge Lorenzo

An unexpected role for a former multi-time champion, but Lorenzo’s switch to Ducati is still a work in progress. If he can sustain the fast learning rate, however, he might be strong enough to regain pre-eminence and join Rossi, Stoner, Lawson, Agostini, and Duke to win titles on different makes.

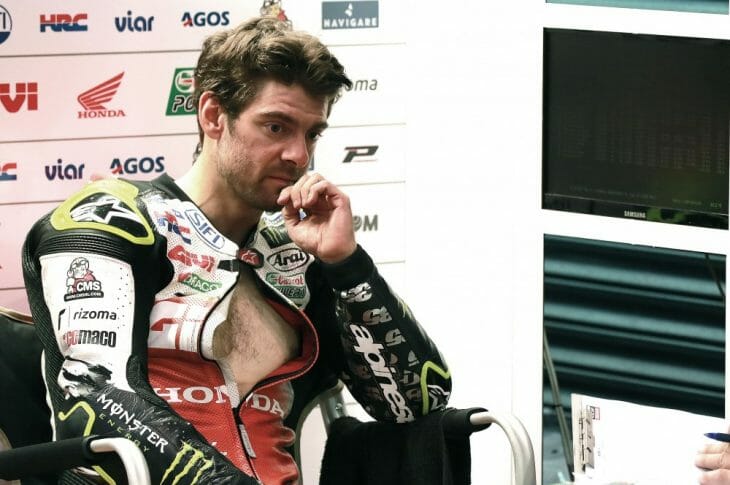

Cal Crutchlow

Fast but at times erratic, Crutchlow is often leaned on by HRC to do all the testing donkeywork as a contracted factory rider in the satellite LCR squad. The Briton has two wins to his name already and has the same equipment at Marquez and Pedrosa at his disposal. A certain podium threat and capable of stealing the odd win when circumstances go his way.

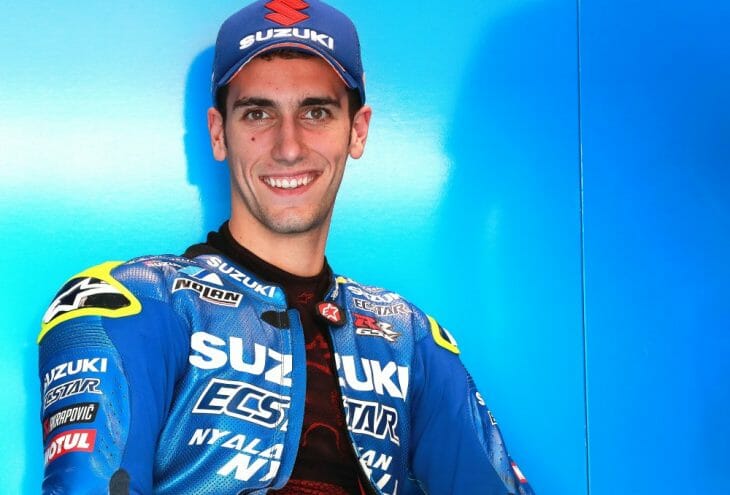

Alex Rins

A title for the Suzuki sophomore is a tall order, but race wins could be available in the right circumstances, and Rins has plenty of high-level support. Given some help by the Japanese team, it will be a big surprise if he is not on the podium at least once.

The Rookies

Takaaki Nakagami

Nakagami bears the hopes not only of Honda but also all of Japan. A patchy Moto2 career (just one win) might not augur well. But MotoGP is a different proposition, and he was top rookie in tests at Sepang, Buriram (an impressive 10th) and until the final day in Qatar as well.

Franco Morbidelli

Rossi’s protégé Morbidelli is calm and collected; his progress in Moto2 was rapid and yet well-controlled; and dominant in 2017. His learning year puts him on a relatively ill-favored private Honda. Give him time and he is bound to impress.

Thomas Luthi

Former 125 champion Luthi had to wait until he was 31 before he finally got his MotoGP chance, by when the ex-125 champ had won 11 Moto2 races and twice been title runner-up. He is teamed alongside 2017 rival Morbidelli. Perhaps that will inspire him.

Hafizh Syahrin

Malaysia’s top rider Syahrin got his break with the Tech3 Yamaha team at the last minute after German Jonas Folger withdrew due to continuing health problems. In six Moto2 years, he has been promising without scaling the heights, and excellent in the wet. His progress in the big class will be interesting.

Xavier Simeon

Simeon’s promotion was a surprise to many after seven mainly undistinguished Moto2 seasons, illuminated by a single win in 2015. Sponsorship connections and the desire for a Belgian rider were credited with the deal with the Avintia Ducati team, but let’s give him a chance.

The MotoGP Tech Race

The normal course of engine development seeks more power, and to make it more manageable.

Honda brought three different-spec engines to pre-season tests, and by the second of three all factory riders had chosen the same—with the emphasis on horsepower rather than good manners. They were also testing a new carbon-fiber swingarm.

Crutchlow believed the engine could be tamed with electronics. Similar thoughts emanated from Ducati, also with more power—along with a chassis development that has addressed and possibly solved the Italian bike’s reluctance to hold a corner line in long turns.

Fairing design is frozen from the first race, with one update allowed during the season.

Fairing design is frozen from the first race, with one update allowed during the season.

But Yamaha has found the unified software an unreliable friend, and after two of three tests were still struggling to find the balance for which the M1 has always been famed. It deserted them last year, and satellite rider Zarco was emphatic in choosing to stick with the 2016 chassis for his campaign, after serial success on it last year.

The Frenchman will go with the latest aerodynamics—an area of major development for all. Windjamming leaders Ducati had an updated and more skeletal version of their fairing-flank box kites; while the rest had moved towards a similar solution, Yamaha ditching the sandwich-sided ducted fairings for boxed-in wings. Honda was testing something similar, along with Aprilia; while Suzuki had shapely side pods giving their bodywork a notable trout-pout.

Fairing design is frozen from the first race with one update allowed. We have not yet have heard the last words.