| February 23, 2018

First Supercross | Supercross, Through The Eyes of a Kid | It wasn’t until the flamethrowers and fireworks went off as the gate dropped on the first 250cc heat race at Oakland that I fully appreciated the evolution of spectacle that is supercross. As a motorcycle journalist and former Team Maico race mechanic I’ve attended my fare share of races—perhaps having become a little jaded to the whole affair. But this time it was different.

By Jeff Buchanan

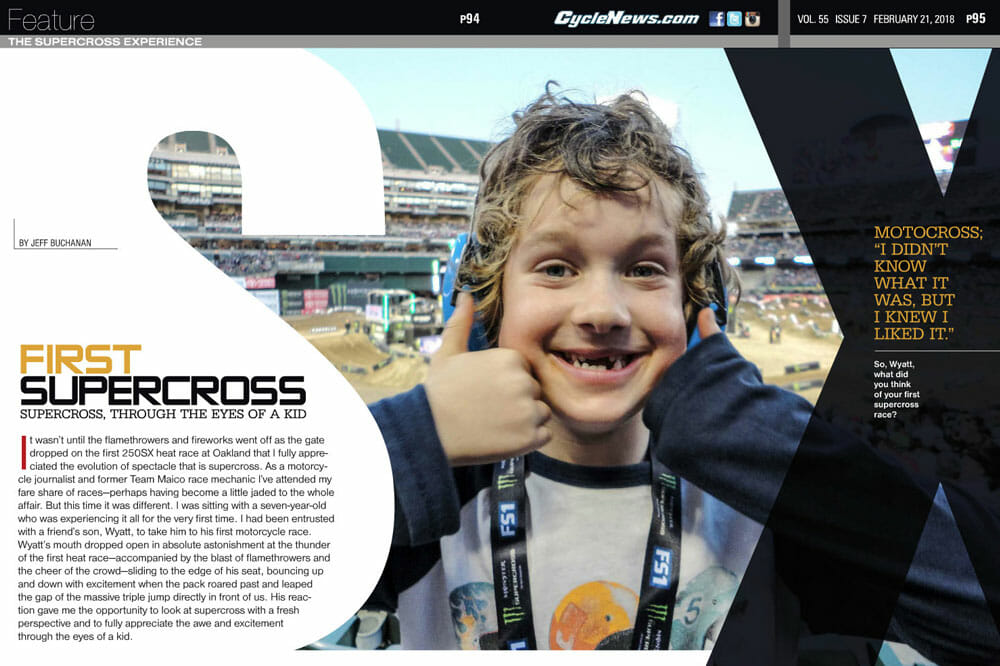

I was sitting with a seven-year old who was experiencing it all for the very first time. I had been entrusted with a friend’s son, Wyatt, to take him to his first motorcycle race. Wyatt’s mouth dropped open in absolute astonishment at the thunder of the first heat race—accompanied by the blast of flamethrowers and the cheer of the crowd—sliding to the edge of his seat, bouncing up and down with excitement when the pack roared past and leaped the gap of the massive triple jump directly in front of us. His reaction gave me the opportunity to look at supercross with a fresh perspective and to fully appreciate the awe and excitement through the eyes of a kid.

So, Wyatt, what did you think of your first supercross race?

So, Wyatt, what did you think of your first supercross race?

LOOKING BACK

The evening in Oakland had me reflecting on my first supercross experience all those very many years ago. I am from the generation that saw its invention. My personal indoctrination to motocross had been in 1971 when my dad took me to the Saddleback Trans-Am. My first exposure to motocross was seeing 500cc World Champion, Swede Bengt Aberg, blast up the entire length of the start hill on the rear wheel of his Husqvarna and then sail down Banzai Hill. I’d never seen or heard anything like it. Motocross; I didn’t know what it was, but I knew I liked it. A moment later the smell of burnt pre-mix from Aberg’s Husky wafted over me. I was hooked.

By the summer of 1972 I was a full-blown motocross devotee riding a Yamaha 100. My fellow moto-heads and I couldn’t believe our ears when a slew of ads hammered AM radio announcing the inaugural “Superbowl of Motocross.” Rock promoter Mike Goodwin had dreamed up the audacious concept of trucking in loads of dirt and transforming the hallowed playing field of the Los Angeles Coliseum into a motocross track. The L.A. venue was site of the first ever Super Bowl, so Goodwin capitalized on the name, which would eventually be morphed into supercross (an amalgam of Super Bowl and motocross) when the indoor stadium series became its own championship.

This is one photo Wyatt will hold on to for the rest of his life. Surely you have one like this, too. You and…?

This is one photo Wyatt will hold on to for the rest of his life. Surely you have one like this, too. You and…?

Although that 1972 event receives the credit for being the first, supercross had roots as far back as 1948, when a track was constructed inside the Buffalo Stadium outside Paris. In 1972, a track was constructed inside Daytona Speedway during Bike Week, utilizing the grass infield in front of the grandstands (with Jimmy Weinert winning the 250cc class and Mark Blackwell winning the 500cc race).

Goodwin understood crowds and hype, so he bombarded Southern California television and radio with high-energy ads to whip up the excitement. He’d lured top European talent with a big purse and start money, pitching the race as Americans versus the world. Announcer Larry Huffman (known as “the mouth”) was brought in to bring the atmosphere to a fever pitch.

Even as an adult, it never gets old walking into a stadium and seeing a motocross track instead of green grass on the floor. Wyatt was mesmerized by it all.

Even as an adult, it never gets old walking into a stadium and seeing a motocross track instead of green grass on the floor. Wyatt was mesmerized by it all.

The atmosphere of the Coliseum that warm July night was electric. Walking through the dark pedestrian tunnel and then having it open up to reveal the track, banners and hay bales laid out over the stadium floor was incredible. For motocross purists—including a number of attending Euros—there was a lot of skepticism about the legitimacy of a genuine motocross track being conjured out of a flat football field. But as night fell and the lights illuminated the stadium it brought an otherworldly aspect to it all. It was different, but after all, it was a dirt course, and it was still all about racing.

In a perfectly scripted night the inaugural Superbowl of Motocross was won by an unknown 16-year old Yamaha-mounted kid from Santee, California: Marty Tripes. An unknown American kid beating a host of European World Champions on American soil added a storybook touch to the evening, cementing the annual race as a must-see. When the tally of 30,000 paying spectators was brought to light, the promoters knew they had something.

The sport of supercross racing has come a long ways since Marty Tripes won what is generally accepted as the very first supercross race—dubbed the Superbowl of Motocross—at the L.A. Coliseum in 1972. More than 30,000 fans checked it out.

The sport of supercross racing has come a long ways since Marty Tripes won what is generally accepted as the very first supercross race—dubbed the Superbowl of Motocross—at the L.A. Coliseum in 1972. More than 30,000 fans checked it out.

What differentiated supercross from motocross, from a promoter’s perspective, was the simple logistics. Before supercross, if you wanted to see a motocross race you had to be a die-hard fan to even know about them. Races were seldom, if ever, advertised, and the tracks tended to be long hauls out into the boonies, where you suffered either freezing cold or blistering heat, making due with under-cooked hamburgers and overworked port-a-potties. On the contrary, a stadium is easy to find, are in the center of a city, and unlike wandering around in the dirt and dust of a motocross venue, offered an opportunity for a spectator to plop down in a seat and have a beer and a hotdog as they watched the races under the cool of night.

The following year, in 1973, Tripes defended his title, winning the second Superbowl of Motocross, this time aboard the new Honda Elsinore and in front of a larger 32,000 spectators. With shades of Boardtrack racing, promoters recognized the cash cow of stadium races and by 1974 the first official championship series—which was comprised of just three races—was won by Pierre Karsmakers of the Netherlands. In the 44 years since, supercross has grown into a significant racing series that continues to sell out stadiums across the country.

Wyatt gets into it.

Wyatt gets into it.

Looking Ahead

I’d watched enough supercross on TV with Wyatt to establish several favorite riders. Since Ryan Dungey’s retirement, Ken Roczen had taken the mantel as his new hero, the German rider having earned equivalent superhero status along with Wyatt’s Ironman and Batman action figures. My status as a journalist writing for Cycle News (and with the good graces of Feld Motorsports) granted me the opportunity to get Wyatt a media pass, and the good people at Jonnum Media arranged a private tour of the Team Honda transporter. Wyatt was silenced when Roczen, fully geared up, came into the rig prior to his heat race. Wyatt looked as if he were seeing one of his superhero action figures come to life. He then got to stand next to Roczen’s number 94 Honda. Each of these little touches took me back to my magical memories at the Superbowl of Motocross in 1972, when I was just a chain-link fence away from Marty Tripes and his factory Yamaha.

Ken Roczen has a new fan for life.

Ken Roczen has a new fan for life.

Sitting in the stands at Oakland, caught up in the excited responses of the 7-year old beside me, I was transported back to my first supercross race, when the sounds and smells of racing mixed with the excited atmosphere of a sold-out stadium. Back in the day, having been limited to satisfying our obsession for motocross through the medium of print magazines, the Superbowl of Motocross granted us the chance to see our heroes racing in the flesh. We were dully awed. To see Wyatt’s wide-eyed, gaping mouth response to the racers as they navigated the course allowed me to be a kid again. I stepped back and relived some of that excited, unabated enthrallment that maturity and adulthood had conspired to quell a bit. I was also able to appreciate how the sport has evolved.

Wyatt experiences the thrills and spills of supercross racing; this was taken probably during one of the many spills that he saw during the Oakland Supercross.

Wyatt experiences the thrills and spills of supercross racing; this was taken probably during one of the many spills that he saw during the Oakland Supercross.

Over the years supercross has changed from its original format of three motos (with points determining the winner—as was the format of traditional motocross), into a more spectator-friendly main event with one winner. This format has proven a crowd pleaser, allowing people who may not be die-hard fans, the opportunity to enjoy the simplified format and make sense of the evening’s qualifying races, helped along by live color commentating.

Feld Entertainment took over the series in 2008, bringing an increased level of professionalism and accessibility to the sport, as well as an aspect of showbiz, with a strong television presence and creating a full day of activities that lead into the night of racing. Feld, a family entertainment-oriented company, has created a user-friendly atmosphere in the form of a pit party with a slew of events geared toward entertaining the entire family.

Over the four-plus decades of supercross the machines have evolved from two-strokes to four-strokes, and modern suspension has seen a radical evolution of what rider and machines are capable of. The triples and quads that toady are leaped with fluidity could not have been imagined back in the ‘70s. Fortunately, supercross survived a potentially damaging hit when Mike Goodwin, the original promoter, the Godfather of Supercross, was caught up in a murder scandal in 1988, convicted of arranging the killing of his business partner and off-road racing legend Mickey Thompson and his wife. Goodwin has always maintained his innocence.

Supercross; still as much a spectacle as it was as in the Superbowl of Motocross days of the early 1970s.

Supercross; still as much a spectacle as it was as in the Superbowl of Motocross days of the early 1970s.

As the evening in Oakland progressed, the lights came on, lending their own kind of magic to the scene. Wyatt cheered every time Ken Roczen came around in his heat race to finish fourth and transfer to the main event. In the 450cc main Wyatt was pleased to see Roczen finish second and actually comprehended that even though his guy finished runner-up, he was (at that time) in the title chase.

When we got home Wyatt hung his media pass on his bedroom doorknob as a souvenir. The next day, after mounting a poster of Ken Roczen next to his bed, off the top of his head, Wyatt said, “Next time let’s go for the whole day.” So, I guess there will be a next time. CN