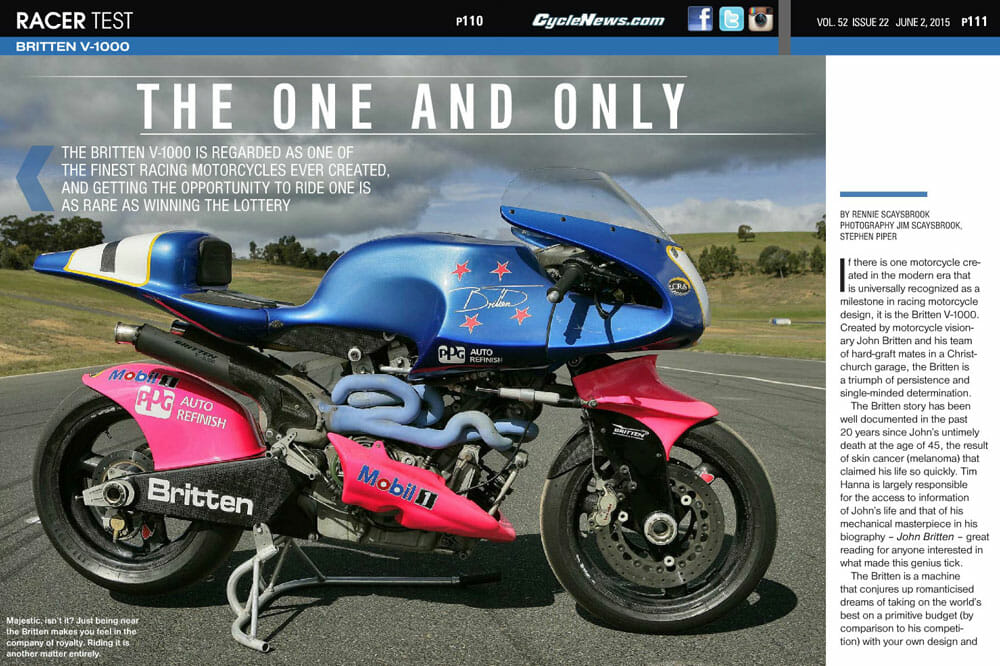

The Britten V-1000 is regarded as one of the finest racing motorcycles ever created, and getting the opportunity to ride one is as rare as winning the lottery

If there is one motorcycle created in the modern era that is universally recognized as a milestone in racing-motorcycle design, it is the Britten V-1000. Created by motorcycle visionary John Britten and his team of hard-graft mates in a Christchurch, New Zealand garage, the Britten is a triumph of persistence and single-minded determination.

The Britten story has been well documented in the past 22 years since John’s untimely death at the age of 45, the result of skin cancer (melanoma) that claimed his life so quickly. Tim Hanna is largely responsible for the access to information of John’s life and that of his mechanical masterpiece in his biography—John Britten—great reading for anyone interested in what made this genius tick.

Photography Jim Scaysbrook, Stephen Piper

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

The Britten is a machine that conjures up romanticized dreams of taking on the world’s best on a primitive budget (by comparison to his competition) with your own design and beating them, a possibility that is now all but impossible in today’s mega-budget, mega-team day and age. Indeed, John Britten’s genius was probably more suited to the ’50s and ’60s, where workshop-savvy and perseverance often triumphed over impossible odds.

The Britten V-1000 machine you see before you is number 003 in a subject line of 10 created before and after his death—seven were completed prior to his demise in 1995, three completed posthumously, with the final unit rolling out of the Britten factory in February, 1999. This is not the machine that sticks out in everyone’s mind—the Daytona 1100cc special that so nearly completed a fairy tail return to the famed American circuit in 1992 with Andrew Stroud (he famously failed to finish with a flat battery) after the team finished a close second in 1991 with Aussie Paul Lewis—but a 1994 build, 1000cc machine that has competed all over the world, and is probably the most raced of the 10 ever created. This machine, as the number 003 suggests, was created when Britten’s dream was in full steam, when the small band of Kiwis criss-crossed the globe, covering America, Europe and Australia, as well as competing in a number of races in its home of New Zealand with riders like Stroud, Jason McEwan, and Stephen Briggs. The 003 V-1000 is also easily the most active of all the remaining machines—not kept in a thick glass case; it gets ridden regularly, and not just plodded around. It gets ridden the way John intended—hard—like a real racebike should, and regularly by the man who created the Britten racing legend, Andrew Stroud.

The fact this is the case is purely down to its owner, Kevin Grant of Auckland. Kevin made his fortune in agriculture machinery, and these days chooses to spend his leisure time displaying his many rare and exotic machines at racetracks and functions in New Zealand and occasionally abroad. Fortunately, he allowed me the chance to fulfill a lifelong dream of riding the Britten, but I’ll confess to having a severe case of the butterflies before I climbed on board it at the Broadford Bike Bonanza in Victoria, Australia.

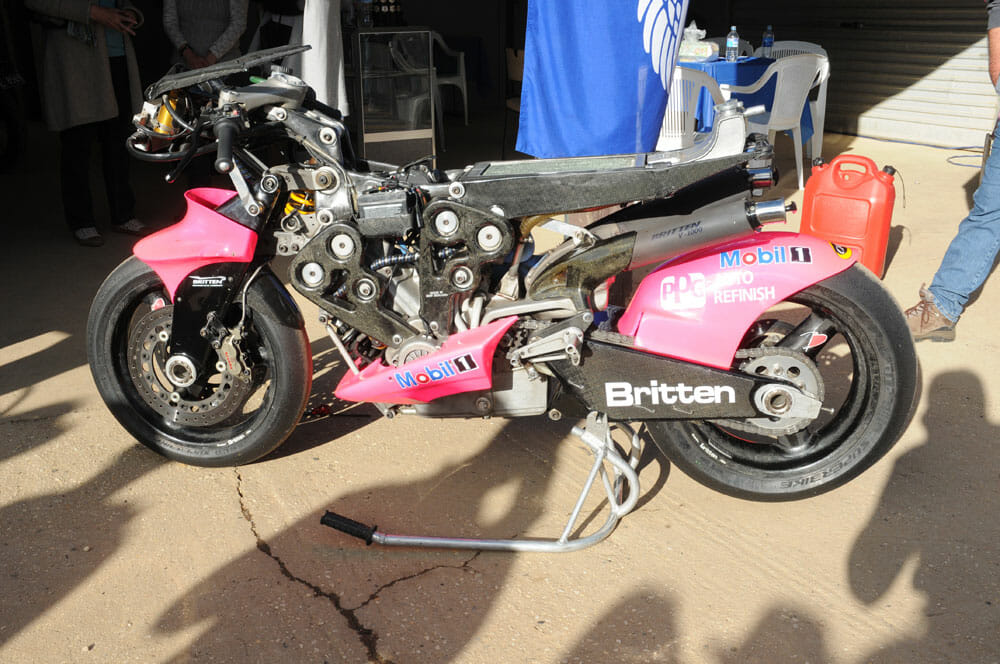

The Britten’s sheer physical presence makes you feel as though you’re in the company of royalty. Everyone who passes stops and gawks at it, pointing, discussing and photographing something that looks unlike any motorcycle created before or since. The Britten had been parked just outside the Motorcycling Australia tent for the majority of the weekend at Broadford, and it never has any less than a two-deep crowd around it.

It is a nervous wait to see if I am going to actually ride this almost mythical machine. Four-times World Grand Prix Champion, Hugh Anderson, is one of the star attractions of the meeting and the only person scheduled to ride the Britten at Broadford. It takes a bit of to and fro, but finally owner Kevin Grant allows me the majority of one session to get a feel for the machine, cut a few fast laps and return it as I found it. That final point can not be stressed highly enough—I am told prior to my laps that this machine is worth conservatively north of $500,000, and if I were to damage it, I will be working for free, forever.

The time finally arrives when I am scheduled to take the track, and with a few choice words from Kevin and Hugh to “watch the throttle down low,” I venture over to the waiting machine that had just been fired on the roller by Anderson.

The Britten needs to be started in third gear due to the engine’s enormously tall compression, and the second the booming twin fired, I reckon there were around 100 people standing in a semi-circle around the blue-and-pink beast. Cameras flashing, pointing fingers and just the general look of awe on people’s faces seemed to be all I could see, as I snicked the Britten into first gear and rolled down pitlane, all the while extremely careful to A) Not run into anything in the rather cramped pits while riding at below 5 mph and B) Not let it stall, which is all too easy thanks to the lack of flywheel weight and the machine’s refusal to idle.

It’s hard to put into words the feeling of utter amazement I had riding the Britten at a snail’s pace down to the track opening. The people crammed into the pits make something of a human corridor as I roll through frantically trying to keep the Britten revving at a point where it won’t stall. Bam, bam, bam, bam—the engine revs with a faster ferocity than a grand prix 250cc two-stroke, and no sooner do I compete one blip that I need to do another because the revs go from 2500 rpm to 8000 rpm back to 2500 rpm quicker than any four-stroke I’ve ever ridden. Coupled with the ultra-fast revving engine is an exhaust note that is totally unique—the Britten sounds similar to a Honda VTR1000 SP1 with Akrapovic pipes mixed with a Yamaha TRX850—a completely different note to anything I’ve ever ridden before, although not as loud as I anticipated.

Leaving the pits my first thought is to keep the Britten revving and upright, because the entry to Broadford’s straight is an extremely tight left-hand hairpin and, with the very limited steering lock on the Britten, it makes for an interesting circuit entry. Once on track, upright and still revving, I give the Britten gradual throttle that has the revs climbing quickly to 7000 rpm in second gear, before it is time to think about the entry to the uphill, 180-degree first-turn right-hander that leads onto the back-straight. It is apparent straightaway, even on stone cold rubber, that this machine is capable of incredible turn and corner speed. The unsprung weight of the Britten is seriously low, with any component that can be made from carbon fiber done so, resulting in turn speed that will nearly equal a 250cc GP machine less than half its size.

Accelerating down the back-straight for the first time is something I won’t forget in a hurry. The Britten picks up revs with such intensity it feels as though it could take on V-twins like a Panigale, and the drive through the rev range is as measured as it is ferocious—it’s just so hard to believe that this machine came out of the garage of one man.

There are a few different bikes on track on this first lap, and I admit it takes me another lap before I feel comfortable enough to start pushing it. However, by lap three, the tires have managed to get sufficient heat into them that I can brake late and hard, accelerate early and hard, and now it is time get down to business.

Exiting the final, uphill 180° left-hand turn onto the front straight in second gear, the Britten is carrying just over 4000 rpm, which is right in the middle of a flat spot in the powerband thanks to the primitive electronic fuel-injection system that was another of Britten’s ahead-of-its-time creations. The throttle at these revs can be a little touchy, requiring the rider to feed the power in quickly to get over this little in drive, stand the bike up on the meaty part of the tire and get the engine spinning up and driving. This engine has so much low-down torque, pulling the chassis over the crest and down the front straight. Third gear is gone in a flash on the Suzuki GS-sourced five-speed gearbox, with fourth gear snatched about 300 feet before the braking marker.

I am warned before I go on track by Kevin to keep the revs below 10,000 rpm, purely for engine conservation, which after five hours of running necessitates a full rebuild, and the best I managed to see on the tacho was about 8900 rpm in fourth gear down the short back-straight before I run out of room. But between 4000 rpm and that final 8900 indicated rpm on the dash, the V-twin Britten is an absolute weapon. This is pure heroin for motorcycle junkies. The power comes in so fast. The almost total lack of flywheel weight sees the tacho climb at a horrendous pace, but the chassis just keeps everything in order and on line, the perfect Ying to the engine’s Yang. I have no doubt that, even now, with a talented rider on board, this machine would still be a serious force to be reckoned with in top-level Superbike racing.

The engine, in all honesty, wasn’t even trying—this thing was built for racetracks like Daytona and Assen, and somewhere like Broadford, with its short straights and constant radius corners is not going to stress it to anywhere near its full potential. I leave myself enough space at the braking marker that I know I won’t drop it on entry, but even though the Broadford track is not going to show me the outer reaches of the engine’s capabilities, it gives the machine ample time to highlight its marvelous chassis package.

Barreling into turn one and laying the machine over on its side, the Britten feels more planted and secure than almost any machine I have ever ridden, only the Aprilia RSA250 Grand Prix machine of Alex Debon I rode felt more nimble. It’s incredible how quickly I feel comfortable enough to give the chassis a bit of stick—I feel completely at home, and any thoughts of working for free for the rest of my life gave way to a kind of euphoria I have never experienced on a bike before or since. The chassis is your friend, working with you and urging you to go harder into the corner than you did before. The feel that comes from the unconventional Girder front-end is utterly tangible. It feels as through you’re running your palm over the contact patch of the tire, and with steering and suspension forces separated, it makes for a ride unlike any other.

That’s what this chassis has over so many I’ve tried before—feel and feedback. You know exactly where you are on the track with the Britten. The front-end doesn’t dive when you get on the Brembo brakes, which, even for 20+-year-old calipers, still have exceptional power and feel. Rather, the suspension simply squats to let the tire load up and grip for when you begin the turning process, which requires only minimal input to begin with such a lightweight chassis and running gear. But it’s not just the front that makes this Britten so confidence-inspiring. The rear suspension is mounted beneath the front, and this totally backwards way of thinking (save perhaps for the Bimota Tesi 3D) gives a foreign but at the same time, totally understandable feel on braking and acceleration.

There’s no denying that the Britten is a stiffly-sprung motorcycle, but that stiffness equates to a motorcycle as rideable than something like a race-prepped Supersport 600 machine, to which the Britten feels almost equal in terms of weight but not dimensions, which are somewhat larger. The rear suspension in particular floats over bumps as if they weren’t there. The front is similarly planted, but will send a bit more of a shock through to the rider that almost gets cancelled out by the rear suspension setup. Again, the minuscule unsprung weight comes to the fore here, but it’s particularly noticeable when fast direction changes are required, such as those leaving the penultimate turn and entering Broadford’s final turn. Two things stand out here. One—the line changeability when in the middle of the corner and, two—the speed at which it goes from full lean one side to full lean on the other.

The approach to turn six is downhill and off-camber, requiring total trust in the front-end. The previous three laps had alerted me to the chassis’ blinding speed of turn, but this particular entry, I deliberately run the Britten wide, with a bit too much speed, to see how easy it would be to get it back on line. In all honesty, it is just too easy. Being more than five feet off line, I simply have to look where I want to go, give a slight tug of the bars and the Britten just follows my commands, and then when it comes time to quickly change direction, with no hint of hesitation the Britten swaps lean angles, with plated suspension, not even the slightest hint of bucking or wallowing, and waits for the throttle to be dialed in. Simply stunning.

And this steering trait belies the fact that at standstill, the Britten is a very large motorcycle. Compared to a GSX-R1100 of the day it feels like a 600, but it feels and looks longer than a Ducati 851 or 888, which were the benchmarks when John Britten designed the machine. That imposing size makes it very comfortable for someone of my 6’1” frame to sit on and tuck in down the straight. The shape of the handcrafted fuel tank does have a similar feel to that of a Ducati, in that it locks you in place under braking with very pronounced curves for your knees to sit in when tucked behind the bubble, but amazingly it also lets the rider get physical, climbing over the front of the bike in corners, which might be one of the reason Andrew Stroud was so successful on the Britten.

I could have ridden for another 30 laps at a decent pace, I wasn’t tired, but I soon came to the realization that I needed to bring the Britten home, back to its owner, who was quietly sweating bullets in the pits. Upon arrival, I also realize how hard I’ve been concentrating, how much attention I’ve been paying to every little nuance of the chassis and every pulse from the engine, and I was actually quite exhausted.

As I roll back to the garage, with clutch in, still revving the engine in the same ferocity as when I took off, an enormous crowd gathers to see the machine come to a stop. And despite my best efforts, I do manage to stall it, but it was about 20 feet from where I have to go, so it looks like I’d done it deliberately.

The smile still hasn’t left my face after my experience with what is undoubtedly one of the finest, most inspiring motorcycles ever created. The Britten will forever be remembered as a truly special piece of engineering, and the fact it was created by a team of mates in a Christchurch garage all those years ago, and not a giant faceless corporation, makes the machine all the more special.

The Britten V-1000 engine

There’s a great part in the Britten documentary One Man’s Dream, where John frantically rushes to the swimming pool to get some extra water to pour into his wife’s pottery kiln. Inside the kiln is the crankcase, and although a potential catastrophe was averted and the case still useable, it gave an insight into just how close to the limit John was working when he designed the V-1000 motorcycle.

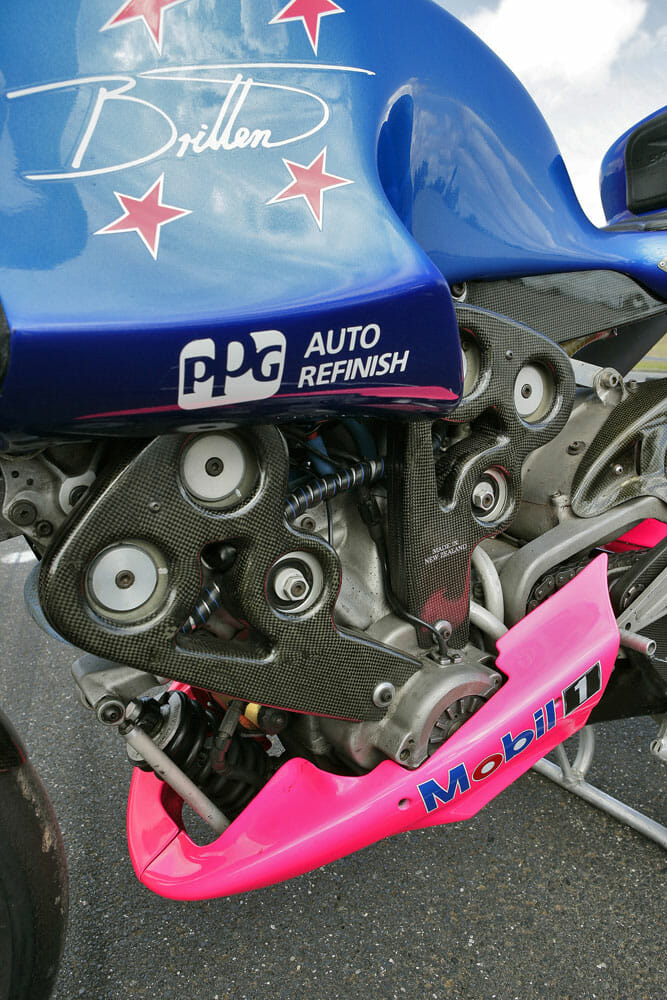

The 60°, DOHC, eight-valve V-twin, with a bore and stroke of 99 x 64mm bore and compression ratio of around 11.5-12.0:1 was designed from the outset to be a stressed member of the chassis—like the Ducati Panigale is today. There are only two parting lines to the engine, to maximize strength and stiffness for use as the stressed chassis member.

The first crankshaft was milled from a solid 4340-billet block of aluminum and the bearing surfaces double-nitrate coated. The crankshaft, in its final format, weighed 27.5lbs and housed sizeable single roller bearings that were set into the crankcases on each side. Later John would employ American company Crower to construct the Britten crankshaft.

Throughout the V-1000’s life John Britten flirted with the idea of a five-valve cylinder head. The idea for this was driven by John’s never-ending search for more horsepower. In its 1992 V-1100 form, the engine would be punching out well over 170hp, which was an astronomical amount for power for its time. The five-valve head did eventually make it onto a Britten V-1000 racebike, but for the majority of the model’s racing life it sported a four-valve head, with the valves driven by a single toothed belt off the crank. The inlet and exhaust valves fitted in the pent-roof combustion chamber sat at an included angle of 30 degrees and were supplied by American company Delwest and made in titanium, weighing an astounding 30 grams each.

The engine sported a wet-sump, and the cylinders were cast as part of the upper crankcase half, but many of the internal engine components were not of Britten’s design. The five-speed gearbox is sourced from a Suzuki GS1100ET, the pistons made by Omega (to his specifications) and the titanium conrods (which had a habit of failing on earlier machines, creating a real mess) were also outsourced, plus a Ducati alternator was used. John did however make all the patterns for the major engine components, and the majority of the chassis components. However, the electronic fuel-injection system proved to be somewhat of a hassle in the early days. The system consisted of a collection of various parts from different manufacturers, but Britten had his own map-design to which they needed to conform. Many teething issues were to arise during development of the original V1000 engine of the late 1980s, with team member Mark Franklin largely responsible for getting the system to run smoothly. The system is fed by twin sequential Bosch injectors per cylinder, tuneable by laptop through the connection on the inside front left of the fairing, but the system can also be richened or leaned out by the rider depending on conditions via the little knob on the left side handlebar—something that was regularly done when the Britten was raced at the Isle of Man.

The cooling system was and still is a rarity in motorcycle design. With John Britten’s steadfast refusal to mount a fairing, and the other problem that the design of the V-1000 meant the radiator would effectively become an aerodynamic hindrance, the decision was made to mount the radiator under the under the seat. High-pressure air is fed to the radiator via an internal duct at the front of the bodywork that runs straight through the fuel tank, while two extra ducts running either side of the radiator duct feed high-pressure air straight through the tank to the airbox. Placing the radiator beneath the seat meant the Britten would be able to maintain its aerodynamic shape, while reducing the radiator’s size and increasing its cooling efficiency. Bingo!

The incredible spaghetti-style exhaust system took 70 hours to complete, so crashing the bike is not an option! The earlier 1100cc model had its exhaust snake together with a final outlet near the rider’s right boot, while this model’s pipe feeds into a collector box with two outlets that exit either side of the rider.

The Britten V-1000 Chassis

John Britten’s V-1000 engine in the grand scheme of things is not groundbreaking (it was still a DOHC four-valve V-twin), but it was for the time. What was groundbreaking, and still is, is the chassis that housed that remarkable engine.

After the first V-1000 ran with a conventional chassis with telescopic forks, John decided that the new V-1000, created in 1991, should run with the engine as a stressed member with the front-end, sub-chassis and swingarm anchoring at various points on the engine.

John was a firm believer in creating things with a difference and his V-1000’s suspension set-up was no exception. Rather than run with conventional forks, John re-worked the classic Girder fork system—one of the earliest came from the pre-war Vincent machines from which he took not inconsiderable inspiration. The rear suspension, with a single Öhlins shock, was also similarly unique and mounted at the front, beneath the front suspension, and hooked up to the swingarm via a series of linkages.

John held a lifelong fascination with old HRD Vincents and took inspiration from a Norton ES2, both with unconventional front-ends, but it is unclear exactly where he got the idea to run a girder front-end from.

Britten used the girder system for four reasons:

- To eliminate suspension stiction under heavy brake loads

- To eliminate fork flex and chatter and retain a constant wheel position relative to the chassis under braking

- The have the ability to use double wishbone geometry, in turn enabling the engineer to dial in the exact amount of squat required under braking

- To increase overall torsional stiffness and reduce weight

That final point was also hammered in with the liberal use of carbon fiber, with the girder fork, front and rear wheel, sub-chassis, swingarm and bodywork all made from the then ultra-expensive material and process (bear in mind this is machine was created only 12 months after the debut of the Cagiva 500cc Grand Prix carbon-fiber-framed machine). The sub-chassis included pick-up points for the front suspension’s upper and lower wishbones, which in turn were located on the cylinder head.

Throughout the machine’s life there would be persistent problems with front-end chatter on full lean. The cause of this was never fully rectified, and Andrew Stroud even remarked that if the Britten were to have a conventional front-end, it would probably be the best handling machine in the world, not to mention one of the fastest.

The Britten girder system, with its carbon-Kevlar wishbones (later converted to aluminum) and Öhlins shock, gave the rider 120mm of suspension travel, but the setup allowed the engineers to dial in an exact amount of pro-dive and anti-dive. The first 80mm of which was pro-dive, the last 40mm anti-dive. This could be altered with the use of different wishbones.

The rear suspension required a rework from previous Britten V-1000 models due to the problem of the shock overheating and losing its damping characteristics. As a result, a sub-chassis attached to the front cylinder head cantilevered the top end of the spring forward from the exhaust header, thus placing it into cooler incoming air. The shock and spring unit was inverted and placed in front of the lower half of the forward facing cylinder and was activated by a bell-crank. The bell-crank’s activation came from a push/pull rod that was attached to the swingarm. All this was done on the same plane, meaning Britten and his team had come up with a novel way of reducing the risk of the shock overheating and still managing to come up with a totally unique solution to the rear-suspension problem.

John used a wet-lay method to create the carbon-fiber parts, weaving carbon fibers impregnated with uncured resin between aluminum rods that established the bones of the woven, pre-stressed structure. This was then filled with foam and faced off with carbon/Kevlar sheet and cured in John’s self-made autoclave oven to create the final part. The sub-chassis weighs an amazing 9.4lbs, the swingarm 6.6lbs, an incredible achievement for its time.

John had the ability to vary rake, trail and wishbone settings, allowing him an almost infinite range of handling possibilities.

Special attention was paid to getting the Britten as aerodynamic as possible, and again, John went his own way and ditched the full fairing in favor of directing the air in and around the machine. John famously said of the design, “I have an engine that is no wider than the rear wheel, so there’s no need for the bottom of the bike to be any wider, either.”

He removed the two side-mounted radiators and utilized a single, horizontal unit mounted underneath the seat—amazingly the system kept the Britten cooler than before—with high-pressure cold air coming in via the two inlets on the front of the shark-nose fairing, and low-pressure warm air exiting near the rider’s legs. The lack of a lower fairing also afforded John Britten the pleasure of letting his gorgeous engine be shown off in all its glory, not hidden behind a bulbous fairing.

As with anything that could be made of it, the front nose fairing, fuel tank, seat and small singular pink side fairings are all made with the carbon/Kevlar method, further lowering overall weight. The tank structure itself was quite large with deep indents for the rider’s legs, but it did enable tall riders like Stroud the chance to fully tuck in. However some riders would later complain the Britten’s ergonomics made it somewhat difficult to ride, with a long stretch to the bars and a rather short space from the seat to the footpegs.

The Britten ran on its own carbon-fiber wheels, created by John and the team. A laborious process like the rest of the Britten V-1000, the wheels were another of John Britten’s masterpieces that was again ahead of the contemporary motorcycle manufacturers of the day. Britten did have the option of running Marvic wheels that belonged to the Kenny Roberts Marlboro 500cc Grand Prix team through friend and colleague Mike Sinclair, but he decided to go his own way, in typical Britten fashion. The offshoot problem with this was the team would often be left with a chronic shortage of wheels at race meetings. CN

|

SPECIFICATIONS: Britten V-1000 |

|

|

Configuration: |

60˚ V-twin |

|

Cylinder head: |

DOHC, four-valves per cylinder |

|

Capacity: |

998cc |

|

Bore: |

99mm |

|

Stroke: |

64mm |

|

Compression ratio: |

12.0:1 |

|

Cooling: |

Liquid |

|

Fueling: |

EFI |

|

Power: |

N/A |

|

Torque: |

N/A |

|

Top speed: |

181.1 mph (est) |

|

Transmission: |

Five-speed |

|

Primary drive: |

Gear |

|

Clutch: |

Dry |

|

Final drive: |

Chain |

|

Frame material: |

Carbon fiber |

|

Frame layout: |

Engine used as stressed member |

|

Rake: |

23˚ |

|

Trail: |

Not given |

|

Wheelbase: |

56.3 in. |

|

Brakes: |

Brembo |

|

Front: |

Twin 320mm discs, four-piston calipers |

|

Rear: |

210mm disc, two-piston caliper |

|

Front Suspension: |

Double wishbone parallelogram girder fork with Öhlins shock |

|

Rear Suspension: |

Front-mounted vertical Öhlins shock via pull-rod rising-rate linkage |

|

Wheels: |

Three-spoke, carbon wheel |

|

Front Wheel: |

17 x 3.625 |

|

Rear Wheel: |

17 x 6.0 |

|

Tires: |

Pirelli Diablo Superbike |

|

Front Tire: |

120/70 R17 |

|

Rear Tire: |

180/60-R17 |

|

Weight: |

317 lbs. (dry, claimed) |

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Click here for more Cycle News motorcycle reviews and news.