Michael Scott | June 2, 2017

Cycle News In The Paddock

COLUMN

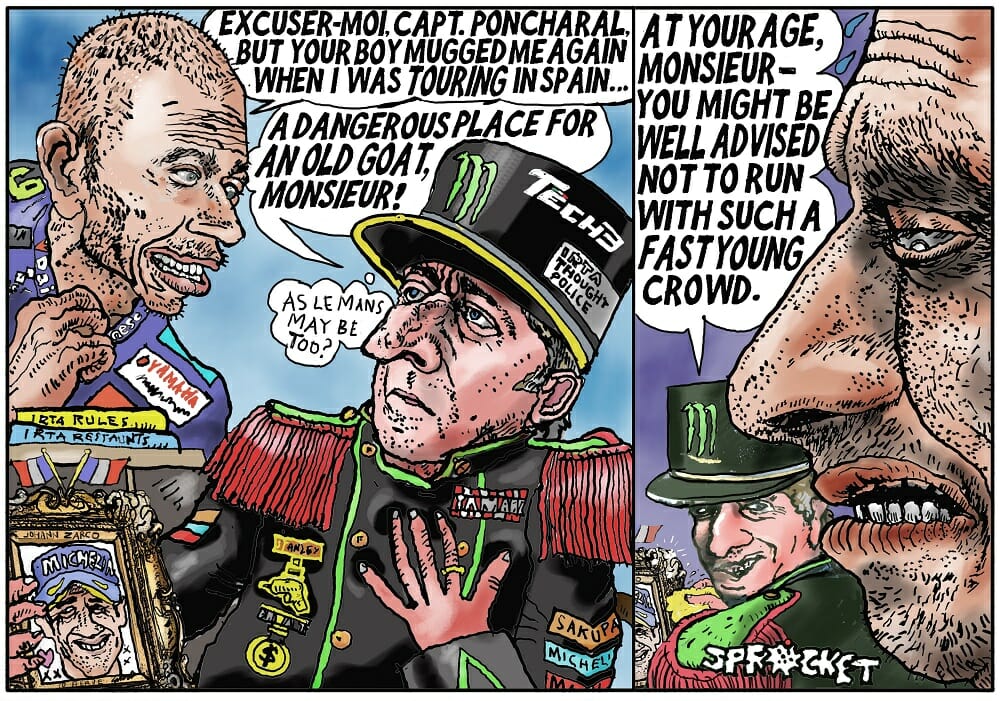

Rubbing Is Racing, The French Way

To be called “a dangerous maniac” by a rider who once enjoyed the same description should be at the pinnacle of any self-respecting GP racer’s ambition. In fact, those aren’t the exact words Rossi chose to describe French parvenu Johann Zarco. But that’s only because he is polite. Or if not actually polite, aware that he needs to guard his words, lest they be twisted and used as a weapon against him.

What he actually said was that Zarco needs “to be more quiet,” and to understand that MotoGP bikes are not the same as Moto2 bikes, in all sorts of important ways.

Primarily they are faster and heavier, and thus more dangerous to crash.

Secondly, a more subtle point, different MotoGP bikes have different characters. In Moto2 everyone is saddled with identical engines and gearing, and nearly all of them are on identical Kalex chassis. It’s hard to find any advantage, so overtaking seldom happens, and is often of necessity a brutal business of bumping and boring.

In the big class, with proper racing bikes, the different makes have different behavior—some, to simplify, excelling at corner entry, others finding advantage on the exit. Because of the different setting and gearing possibilities, there is even variation between bikes with the same badge on the tank.

This makes it possible to overtake using tactics rather than brute force. Brains rather than brawn.

And that is what Valentino would like the young Frenchman to understand.

There is, in all this, a considerable element of pot versus kettle. When Rossi arrived in the 500cc class in 2000, his forceful riding ruffled many a feather. There are a number of famous incidents over the years—like the bump-pass on Gibernau at Jerez in 2005, and duffing up Stoner at Laguna Seca in 2008, for instance. And even last year, he was accused of dangerous riding by Lorenzo at Misano. “Other riders overtake more clean,” the Spaniard said.

Lorenzo is fond of such accusations, but the pot-kettle syndrome rears up once more. At least he admits it, pointing out repeatedly that he was disqualified for one race back in his 250cc days for taking out another rider (de Angelis, as it happens, or as he is nicknamed “d’Angerous”). He (Jorge) learned his lesson, he now says, and back in 2013 called for the same penalty to be applied to Marquez, after the hard-and-fast new boy gave him a major last-corner lunge at that same Jerez hairpin.

Marquez has come in for even more criticism than Rossi, and interestingly enough hasn’t said too much about Zarco. Not yet, anyway—and probably won’t, being a fan of the “rubbing is racing” mantra.

His silence is despite being one of the riders who got minced at Jerez. Where the double Moto2 champion was on a major charge for a fourth race in a row.

Just to recap: in Qatar, his first MotoGP race, he forced into the lead on lap one from the second row, and was going away when he crashed out on lap seven.

In Argentina he qualified 14th and was up to sixth after only five laps. He got as high as fourth in the race, and finished fifth.

In Texas he qualified and finished fifth, but in between he had a real wrestling match with Rossi, including punting him off the track at one point, with Rossi lucky not to crash.

Then in Jerez, he qualified sixth and got away well, and at once set about those in front of him. He left Rossi trailing and had disposed of both Iannone and Crutchlow—two notable hard battlers—by the second lap.

No respecter of reputations, he then set about Marquez and got ahead of him for second, if only for a lap. He ended up fourth, and easily first Yamaha.

And all this on a year-old satellite Yamaha. In his first season.

Zarco is an interesting character: analytical and intelligent. And very loquacious, seldom answering a simple question with anything less than several carefully considered paragraphs. He won two Moto2 titles in an equally considered way. Only once did he get mental, when he knocked Sam Lowes off at Silverstone. More usually, he specialized in staying calm and saving his tires then pushing away at the end.

In this way, he spoke respectfully about Rossi, after following him for much of the race in Texas. In studious fashion, after his first lunge had been unsuccessful, he was able to learn how Rossi preserved his tires, and was able to be as fast at the end of the race as at the beginning. This is his “serious” mode.

But it seems all this consideration goes out of the window as soon as the green light goes. Earning him the enviable accolade of “dangerous maniac.” And he’s hardly even started yet. CN