Alan Cathcart | June 23, 2017

The Superleggera is a new benchmark for the sportbike category—irrespective of the number of cylinders.

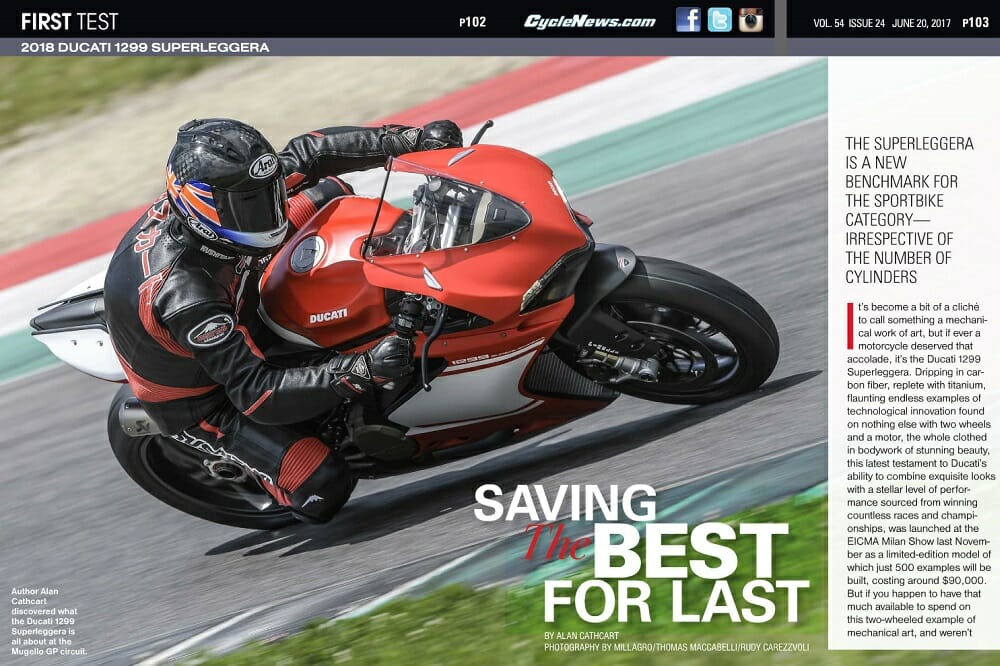

Author Alan Cathcart discovered what the Ducati 1299 Superleggera is all about at the Mugello GP circuit.

Author Alan Cathcart discovered what the Ducati 1299 Superleggera is all about at the Mugello GP circuit.

It’s become a bit of a cliché to call something a mechanical work of art, but if ever a motorcycle deserved that accolade, it’s the Ducati 1299 Superleggera. Dripping in carbon fiber, replete with titanium, flaunting endless examples of technological innovation found on nothing else with two wheels and a motor, the whole clothed in bodywork of stunning beauty, this latest testament to Ducati’s ability to combine exquisite looks with a stellar level of performance sourced from winning countless races and championships, was launched at the EICMA Milan Show last November as a limited-edition model of which just 500 examples will be built, costing around $90,000.

But if you happen to have that much available to spend on this two-wheeled example of mechanical art, and weren’t quick enough on the draw after its Milan Show debut to put a deposit down, you lost out. All 500 bikes are already spoken for, netting the VW/Audi-owned Italian manufacturer a cool 45 million of extra revenue, as well as untold kudos for producing what is, even more than its 1199 Superleggera sister that Ducati produced three years ago in 2014, most assuredly the finest street legal motorcycle I’ve yet had the privilege of riding.

Click here to read this in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MILLAGRO/THOMAS MACCABELLI/RUDY CAREZZVOLI

Yet the 1299 Superleggera also marks a significant landmark in Ducati history, beyond its sheer unmatched excellence in conception, and execution. For with the advent next year of Ducati’s first V-4 Superbike, this is the last of the line of the Italian firm’s series of Desmo V-twin street-legal race bike; the ultimate evolution of this unique format which has so far garnered 14 World Superbike Riders titles and 15 Manufacturers crowns, in winning 329 races to date in the past 30 seasons. It’s a line which began in 1974 with the debut of the green-frame 750SS, of which just 401 examples were ever made as a pretty close replica of Paul Smart’s Imola 200-winning factory Desmo V-twin, just as the new Ducati 1299 Superleggera is to the factory F17 Superbikes being raced this season by Chaz Davies and Marco Melandri. Actually, it’s even better than them chassis-wise, with a carbon-fiber semi-monocoque frame structure that saves 3.7 pounds in weight over the racer’s heavier aluminum equivalent, and it’s pretty close in engine performance, too, with a claimed 215 bhp/158.1 kW on tap at 11,000 rpm, 15 bhp more than the Panigale R currently leading the FIM Superstock series.

Ducati’s new 1299 Superleggera is the fastest and most powerful production twin-cylinder street bike yet offered for sale.

Ducati’s new 1299 Superleggera is the fastest and most powerful production twin-cylinder street bike yet offered for sale.

Having begun my racing career back in the mists of time as one of the 401 lucky owners of a green-frame 750SS I bought new in 1974, I still race in Classic F750 events on what is apparently the last such genuine bike to be used in something approaching anger on the race track. So for me the honor—no other word for it—was especially meaningful to be one of the eight journalists from around the world invited to sample the 1299 Superleggera at the Mugello GP circuit. Riding this two-wheeled work Desmodromic art composed of magnesium, titanium, aluminum and carbon fiber, scaling a featherweight 344 pounds dry, or a mere 392 pounds ready to roll with a full 4.5-gallon fuel tank, was an undoubted thrill. “Created to provide quintessential performance” that’s Ducati’s proclaimed axiom behind the development of this bike, and after riding it I reckon its engineers have hit the bulls-eye. That’s an opinion perhaps inevitably shared by the firm’s CEO Claudio Domenicali, who rode the Superleggera the day before I did, and pronounced himself proud of what his men had achieved. They don’t come any better than this – nor any more exquisitely engineered.

Settle aboard the Superleggera’s relatively plushly padded 32.7-inch high seat, and you’ll encounter an unmistakably racy riding position, with quite a lot of your body weight on your arms and shoulders. Thumb the starter button and relish the muted sound of thunder from the tubone (big pipe!) race exhaust supplied free with the bike as part of the race kit that was fitted for my ride, which further increases power by five bhp via with its massive 3.1-inch diameter drainpipe collector issuing through the twin silencer outlets in the space under the seat, select bottom gear—and you’re off. That’s the last time you’ll need to touch the clutch lever before you return to the pits and stop the Ducati, for while the auto-blipper system fitted is switchable, you’d be crazy to turn it off because it works so smoothly and so well. It delivers a seamless backshift in every gear without your fingering the clutch lever, which means you can focus 100 percent on hitting your braking markers and picking your turn-in for a given bend.

Only 500 Superleggeras are being manufactured and all have been sold in advance of production at a hefty $90,000 (22% Italian tax) price tag.

Only 500 Superleggeras are being manufactured and all have been sold in advance of production at a hefty $90,000 (22% Italian tax) price tag.

However, you don’t have to work the gear lever very hard on the 1299 Superleggera, and that’s because of the massive extra midrange punch from this ultimate version of the Superquadro motor. It’s no longer critical to choose the right gear for each section of track in order to keep up momentum, as it is with the much less torquey 1199 Panigale—in fact, it’s better to use one gear higher in many places than you might otherwise think of doing, and hold that gear from way low to way high. I found I could lap the entire 3.259-mile Mugello circuit from the end of the .6 mile-long main straight back to the start of it with just three gear changes, in spite of the quartet of chicanes and the steep climb up to Arrabbiata one and two turns. I’d use second gear for San Donato at the end of the straight, short shift into third climbing uphill to the Luco chicane, and then I could hold third gear all the way round the rest of the track to the short straight after the Biondetti chicane, when I’d grab fourth briefly before backshifting to third for the long, long Bucine downhill sweeper on to the main straight. To convince myself I wasn’t being lazy, I checked the onboard lap timer in the DDA/Ducati Data Analyzer that’s included in the race kit and was fitted for my ride, which you set with the flash button as you cross the startline, then leave the GPS mounted at the front of the bike to trigger each lap. A comparison with using the gears and revving the bike hard told me I was going faster the lazy way, which let me focus more on choosing a line and maximizing turn speed via the surprisingly flexible motor.

The 1299 Superleggera starts to pick up engine speed a bit faster just above 5000 rpm, and from there to its torque peak at 9000 rpm, there’s a delicious wave of grunt that you look forward to surfing each time you catch it. But even after that peak has been reached the midrange torque doesn’t fall away—it stops building, but stays pretty much constant all the way to 11,000 rpm, by which point the orange shifter lights either side of the TFT dash will start to light up to tell you to hit another gear before they flash red brightly at 12,000 rpm in the bottom five gears, to tell you that you’re about to hit the 12,500 rpm soft revlimiter. Being an RBW digital throttle there’s no cutout—you just stop building speed and revs. But with the broad spread of power and torque the 1299 Superleggera now has, there’s no need to rev it right out to the limiter like on the smaller-cubed, less grunty 1199 Panigale—just ride it like some sort of twist’n’go mega-scooter by holding third gear for most of the lap, and surf that torque curve.

The ultra short-stroke 1285cc Superquadro engine, measuring 116 x 60.8mm now produces 215 bhp at 11,500 rpm, 15 bhp more than Panigale R.

The ultra short-stroke 1285cc Superquadro engine, measuring 116 x 60.8mm now produces 215 bhp at 11,500 rpm, 15 bhp more than Panigale R.

The combination of level 4 DWC and DTC traction control set at level three (both out of eight) delivered intoxicating drive out of turns, with the extra torque giving no hint of understeer under power. The Superleggera hugs a tight line as you wind on the revs thanks to the new DSC/Ducati Slide Control program which helps it close a turn on the throttle, as well as the dialed in chassis geometry and the sublime compliance of the Öhlins rear shock. Where you point the Superleggera is where it heads for; it’s an ultra-precise, predictable package that’s so enjoyable and rewarding to ride, whose enhanced electronic rider aids make doing so even safer and more confidence inspiring than before.

For the DSC lets you accelerate harder and earlier through a corner in a controlled drift, which in turn means you finish turning sooner and can thus nail the throttle wide open sooner, with the highly effective DWC doing its job of keeping the front wheel on the ground to avoid time-wasting wheelies. I’d like to be able to tell you that I was doing this every lap at every turn, but working your mind up to doing this is a bit like convincing yourself that you can take a big handful of brake on the angle deep into a turn on a hub-center bike like a Bimota Tesi or Vyrus—it’s only when you break through the mental barrier of doing so just once and find you haven’t crashed, that you’ve reprogrammed your mental mindset.

Well, toward the end of my stint on the Superleggera I was getting the hang of doing this at Palagio, the exit of the tightest of the chicanes and probably the slowest corner on the track. But I could honestly feel the rear Pirelli SC1 race tire the Ducati was wearing for my test starting to walk under me there, without digging in and highsiding me, while at the same time avoiding running too wide for the exit, but staying close to the left for the next right-hander at Correntaio. I can’t wait for the trickle-down effect to take place so I can try to improve my DSC technique on something that doesn’t cost 90K new, and a mountain of cash to fix crash damage!

A huge array of carbon-fiber, magnesium and titanium components justify steep cost of this exquisitely produced motorcycle, the last in the line of Desmo V-twin ultra-bikes.

A huge array of carbon-fiber, magnesium and titanium components justify steep cost of this exquisitely produced motorcycle, the last in the line of Desmo V-twin ultra-bikes.

But hard though it is to ignore the extra power and greater torque of this EVO-motor, it’s the very refined handling of the 1299 Superleggera that really impresses. However, to begin with I found myself doing something I hadn’t been prepared for, which was to oversteer into the apex of a turn, which meant I repeatedly had to pick the Ducati up again, and correct my line. I’ve been riding on carbon wheels ever since 1994, when I began helping Dymag develop such a design by racing on them, so I know how much they influence turn-in and steering, which is a huge amount, and I’m always ready to compensate for them. You have to focus on being more delicate in steering the bike, which I’d thought I was doing. But then I realized that I hadn’t taken into account the even lighter weight of the new Superleggera’s carbon fiber chassis compared to its 1199 predecessor’s magnesium frame, or indeed the Davies/Melandri aluminium item, as well as all the copious other black magic bits on this uber-Desmo V-twin sportbike.

This made the Superleggera even lighter steering than the Chaz Davies Superbike I last rode at Imola 18 months ago, when flicking from side to side in the quartet of Mugello chicanes. I thought I might be imagining this until Ducati test rider Alessandro Valia confirmed my impressions afterwards, but the lighter carbon-fiber chassis structure and all the other CF parts definitely make the new Ducati more nimble and responsive in changing direction, especially at lower speeds, when it turns super-easily and tightly. This bike is faster steering and more agile than any other Desmo V-twin I’ve yet ridden, and that includes the current factory superbike. Too bad the Superleggera can’t be homologated for WorldSBK—too exclusive, you see: they’re not building enough of them to qualify for homologation!

Carbon-fiber semi-monocoque doubling as the airbox bolts to the top of the 90-degree V-twin Desmo engine.

Carbon-fiber semi-monocoque doubling as the airbox bolts to the top of the 90-degree V-twin Desmo engine.

Yet this is the chassis format which defeated Valentino Rossi in his two years at Ducati in 2011-‘12, leaving him claiming that the D16’s carbon frame that was essentially identical in concept to the Superleggera’s, gave him no feel from the front end. He eventually insisted on a conventional Deltabox frame format which wasn’t any better, judging by his results. This in any case overlooks Casey Stoner’s achievements in taking the carbon-framed Ducati Desmosedici to victory first time out at Qatar in 2009, and scoring three more race victories that season en route to fourth place in the championship. Stoner not only rode for Ducati when they switched from the steel trellis frame to the carbon one, but also tested an aluminum one, and said that the carbon-fiber chassis was “a much better bike.” Apparently he still believes that by the end of the 2010 season, it was so well developed he could have won every race with it, if he hadn’t moved to Honda by then!

Okay, so I’m not Valentino but in clocking a final-third-of-the-grid Italian Superstock lap time on the Superleggera, I truly had confidence in the way the front end spoke to me, allowing me to keep up turn speed in Mugello’s swoopy, sweeping turns. Furthermore, the way that Ducati has compacted the mass of the bike with the Superquadro engine architecture, makes for a motorcycle that is very agile and predictable in the way it changes direction, and the 1299’s slightly sharper steering geometry versus the 1199 is surely an element in that, too.

The Superleggera at home at Mugello.

The Superleggera at home at Mugello.

It was rewarding to put your faith in the front Pirelli and keep up momentum in the Mugello chicanes, or sweeping downhill through Ravelli and uphill at Arrabiata 1, because there was good feedback from the front end even on the side of the tire, making braking deep into a turn then letting off the brakes to keep up turn speed a valid option. And thanks to the stiff yet light chassis it pays off to be quite aggressive in changing direction on the Superleggera, because you can speed up doing so without the bike feeling nervous or flighty. But the Superleggera was also very stable in a straight line, with the taller screen from the race kit fitted for the test. Squatting behind this down that long front straight, molded to the fuel tank as you click sixth gear at 11,000 revs just as you cross the startline, with the deep-throated but muted growl from the 2-1-2 race kit exhaust exiting the twin silencers just below your seat and altering an octave as you hit top gear, was motorcycling nirvana.

The Brembo brakes are absolutely superlative, and it takes longer than I had on the Superleggera to start exploring their limits meaningfully. By swapping the pages on the TFT dash I saw 183 mph on the speedo down the .6-mile-long main straight with its long downhill entry—this is a fast bike!—before stopping hard and backshifting into the second-gear right-hander of San Donato that lies at the end of it just as I passed the 650-foot board. Yet each time I mentally cussed myself because it seemed I’d braked too early, because those radial Brembos are so effective, combining balls-out stopping power with so much feel and good modulation as I searched for the right turn speed in a bend. And there was definitely more engine braking available in the Race mode I was using than is usual nowadays (don’t touch the clutch lever!) without, all without upsetting the stability of the Ducati under braking. Magic. Drive out of a turn was also improved. I could feel the Superleggera jump out of a second or third gear corner really aggressively, but still controllably with excellent grip thanks to the Pirelli rubber, Öhlins rear shock and that new DTC EVO electronic program. Acceleration is truly phenomenal, but it’s not explosive because it’s delivered so smoothly, and without any steps in the powerband. The legendary connection between you throttle hand and the rear wheel is there in spades.

Straightforward and informative.

Straightforward and informative.

With just 10 laps of one of the world’s great racing circuits aboard this peach of a bike, I will admit I did almost no playing around with the ever more sophisticated electronics package, relying instead on Alessandro Valia’s chosen settings. These best of all prevented me frightening myself big time with a repeat of the massive sixth-gear wheelie at 300+ k’s towards the end of the main straight that I once suffered testing Max Biaggi’s factory Aprilia RSV-4 there. That needed a swift change of underwear, but on Valia’s setting of four out of eight on the DWC there was no repeat performance, although the Superleggera did occasionally pop the front wheel in the air while I was slightly cranked over exiting the Borgo San Lorenzo chicane. No worries, though, the Ducati just shook its head a couple of times and resumed normal service. It felt very stable and forgiving, especially at high speed.

The Superleggera features Bosch Cornering ABS, plus several MotoGP-derived electronic programs for the first time on any Ducati street bike.

The Superleggera features Bosch Cornering ABS, plus several MotoGP-derived electronic programs for the first time on any Ducati street bike.

Once you learn to exploit its ultra-light steering and ease in changing direction correctly, the 1299 Superleggera is a super-satisfying as well as a rewarding motorcycle to ride fast on. You can practically do so on autopilot, changing gear just when it feels right without necessarily waiting for the shifter lights to flash, while reveling in its responsive midrange and poised handling. Ducati—this is a very fine motorcycle, no question it’s the best you’ve ever made with lights and a license plate. Job done.

Nothing succeeds like excess, and the Ducati 1299 Superleggera is certainly proof of that, as a fitting last of the line in the Desmo V-twin dynasty. Ducati has fittingly saved the best till last, for this Desmodromic jewel of a motorcycle is practically faultless and totally addictive, as well as a magnificent beat-that demonstration of Ducati’s engineering expertise. Even more than with the 1199 Superleggera, kudos to Claudio Domenicali for sanctioning the development of the ultra-light 1299 “Superleggerissima,” compliments to his engineers for creating it, and congratulations to all 500 of you lucky devils who’ve ordered one. More than ever this time, I hate you all! CN

|

SPECIFICATIONS: 2018 DUCATI SUPERLEGGERA ($90,000)

|

|

ENGINE:

|

Superquadro, liquid-cooled, L-twin, 4-valves-per-cylinder,

Desmodromic

|

|

DISPLACEMENT:

|

1285cc

|

|

BORE X STROKE:

|

116 x 60.8mm

|

|

COMPRESSION RATIO:

|

13.0:1

|

|

POWER:

|

158.1 kW (215 hp) @ 11,000 rpm

|

|

TORQUE:

|

146.5 Nm (108.0 lb-ft) @ 9000 rpm

|

|

FUEL INJECTION:

|

Mitsubishi EFI, twin injectors per cylinder, Ride By Wire

|

|

EXHAUST:

|

2-1-2, 2 catalytic converters

|

|

TRANSMISSION:

|

6-speed w/Ducati Quick Shift (DQS) up/down

|

|

CLUTCH:

|

Hydraulically controlled slipper/self-servo wet multiplate clutch

|

|

FRAME:

|

Monocoque, carbon fiber

|

|

FRONT SUSPENSION:

|

43mm USD Ohlins FL 936 fork, fully adjustable

|

|

REAR SUSPENSION:

|

Single Ohlins TTX36 shock w/ titanium spring, carbon-fiber single-

sided swingarm, fully adjustable

|

|

FRONT WHEEL:

|

10-spoke carbon fiber 3.50 x 17 in.

|

|

REAR WHEEL:

|

10-spoke carbon fiber 6.00 x 17 in.

|

|

FRONT TIRE:

|

Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa SP 120/70 ZR17

|

|

REAR TIRE:

|

Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa SP 200/55 ZR17

|

|

FRONT BRAKE:

|

2 x 330mm semi-floating discs, radially mounted Brembo Monobloc

Evo M50 4-piston calipers w/ cornering ABS

|

|

REAR BRAKE:

|

245mm disc, 2-piston caliper with cornering ABS

|

|

SEAT HEIGHT:

|

32.5 in.

|

|

WHEELBASE:

|

57.3 in.

|

|

RAKE:

|

24°

|

|

TRAIL:

|

3.86 in.

|

|

FUEL CAPACITY:

|

4.5 gal.

|

|

CLAIMED DRY WEIGHT:

|

339.5 lbs

|