Larry Lawrence | April 19, 2017

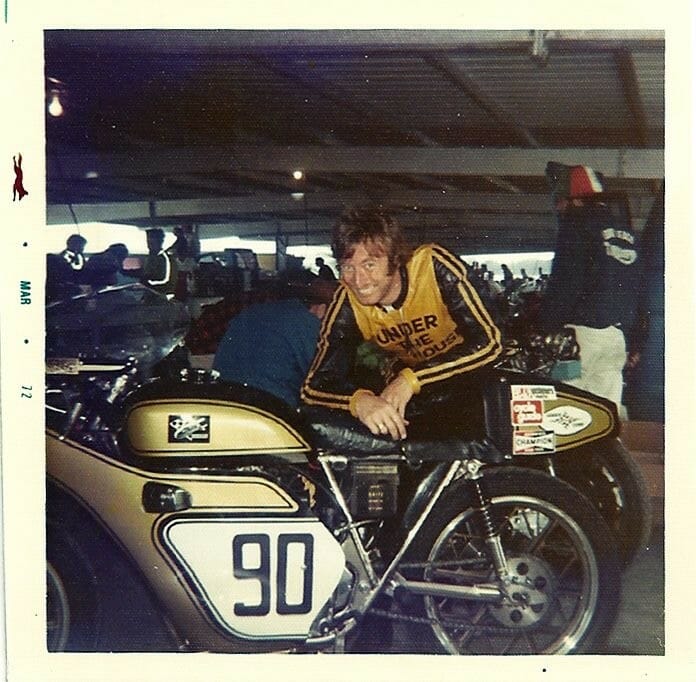

George Kerker, founder of Kerker Exhaust Systems, during his racing days at Daytona.

They say history is written by the victors and such is the case in the world of motorcycle performance exhaust systems. Kerker pipes are still made today, but the company was purchased by longtime rival SuperTrapp in the early 1990s and when you read the “About” section today on SuperTrapp’s website, Kerker gets a small paragraph and there’s nothing of the original founder of the company George Kerker.

It’s difficult to find a lot about George Kerker today via web searches, but fortunately he was such a conspicuous character, that those who knew him remember.

Kerker was one of the wild men who helped get Superbike racing launched on the west coast in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Road racing to that point was a proper imitation of European GP racing, with tidy riders racing purpose-built full faired and small racing motorcycles. Kerker and his fellow production racers busted the mold. They raced large, loud, gnarly-handling streetbikes and got them around the corners anyway they could, even if it meant putting your foot down, sacrilege in the traditional road racing world. And then there were the wheelies, also a no-no to the traditionalist, but so much fun to do on these early Superbikes.

The fans loved it, which only served to further tick off the old guard.

And then there was the legendary time when Kerker took a victory lap trailing his naked girlfriend on the back! Even the traditionalist had to smile at that one.

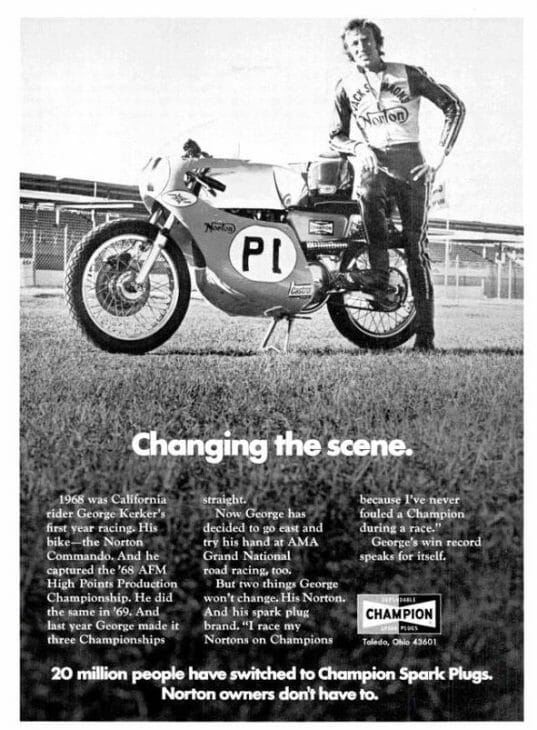

As you might be able to tell by now, Kerker was a colorful figure to say the least. He was an artist who’s medium was bending pipes. That led him into making custom racing exhausts for early Superbikes, first for Moto Guzzis and Nortons and later he built one of the early four-into-one racing pipes for the revolutionary Honda CB750.

When he wasn’t making racing pipes Kerker led the prototypical Southern California disco lifestyle. The early 1970s was an era in Southern California where disco was sweeping the nightclubs. Kerker was a type of West Coast version of John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever! He and his girlfriend were considered two of the best disco dancers in So Cal and they regularly won dance contests. The scene was full of recreational drugs. They were considered fun, something to enhance the frivolous nightlife and George was part of that craze.

While many of his fellow racers of the early 1970s pulled into the race track driving an Econoline van with a greasy buddy sitting in the passenger seat, when Kerker drove up, you knew he was something different. He’d be driving a split-window Vette towing his race bike on a trailer. He’d have a gorgeous girl sitting next to him and he often was wearing same wide bell bottoms and long floppy collars, he’d sported on the disco floor the night before.

And Kerker was fast. He was so good that he would lap riders in short club sprint races. Kerker thought it would be a good idea to warn the lappers he was coming and mounted an ambulance siren below the seat of his purple Norton race bike. “George would come up on other riders so fast that he hit the siren to let him know he was coming and to get the hell out of the way,” remembers fellow racer Harry Klemm. “You could hear the siren going off all around the track. He scared the crap out of countless guys with it. It was the cowboy days of “pre-superbike” racing.”

In 1972 Kerker was part of a group of Southern California racers who raced in front of what was, at the time, perhaps the biggest crowd ever to see a motorcycle road race in America. It was a Los Angeles Times promoted car road race at Riverside with motorcycles as part of the show. A reported 80,000 people watched Kerker, on a near stock Honda CB750, finish second to Pat Evans on a Yamaha TR-3.

A Champion Spark Plug ad featuring George Kerker.

A Champion Spark Plug ad featuring George Kerker.

Kerker, with his connection to Berliner Motor Corp that imported a variety of European brands, was also instrumental in getting several police departments to switch to Moto Guzzi motorcycles and helped setup the bikes for police use.

While preparing for Daytona one year Kerker worked countless hours with little or no sleep preparing his motorcycle, according to friend and racing travel mate Steve McLaughlin.

“He’d been up for days and we set off for Daytona,” McLaughlin remembers. “George was taking speed, which was pretty common for long-haul drivers back then. I was talking enthusiastically to him about one subject or another and he suddenly looked at me and said, ‘This pisses me off! I have to take drugs to keep amped up and you do it naturally!’”

Kerker was a part of the famous Norton Gang, a group of Norton road racers who helped foster big-bore production racing in Southern California, which was a forerunner to the AMA Superbike Series. Kerker was also one of Yoshimura’s first riders when he raced a Honda CB750 in 1972 for the then new to America company.

Kerker pipes gained an excellent reputation among the racing community, but he was doing his work on a small custom basis. He couldn’t scale up quickly enough to meet the growing demand, so he sold his namesake company. He briefly tried coming back with another header company called Winning Performance, but it was short-lived.

By the late ‘70s things began spiraling out of control for Kerker. His girlfriend was paralyzed in a freak accident while changing a lightbulb in their apartment. Friends say George fell deeper into addiction. In late September of 1977 Kerker was found dead in his Van Nuys shop. He’d committed suicide.

He was just 35.

The final round of the AMA Superbike Series of 1977 at Riverside was named in Kerker’s honor.

Even though he had a brief life, Kerker and his exhaust company left a lasting legacy in the sport. He also left lifelong impressions with those with which he crossed paths.

“I only met Kerker once, he came by Racecrafters on Sunset in the old location, I think it was in ’72 or ’73.” said legendary author and road racing guru Keith Code. “The ‘annex’ was in an old drug store building and chock full of widow parts. Pierre and I were building a 550 Honda for club racing. Pierre and Lyn had just bought Kerker pipes. George seemed pretty mellow, maybe a little too mellow (Code smiles). I knew his reputation and I’d just raced at OCR on Pierre’s bike and George was impressed with the lap times we’d turned on the bike. It was one of those moments for me that really counts. I was a nobody Griffith Park canyon guy and the encouragement hit the right chord.”