Michael Scott | March 3, 2017

Wings are banned. Progress has been jammed. MotoGP has taken another backward step away from being a genuine sphere of valuable engineering research.

Or has it?

Perhaps the opposite—although in areas of development other than engineering.

Creative engineering in racing is most often not a matter of advancing knowledge and benefiting the human race but instead finding a way round the regulations. Any real advance is by coincidence.

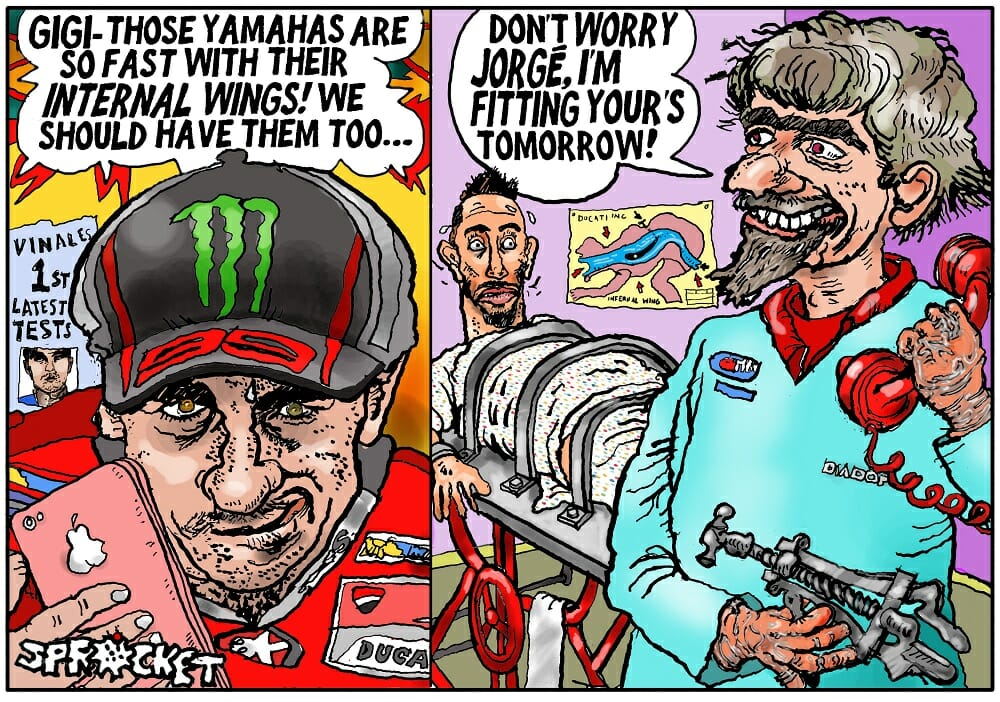

As the second round of tests ended in Australia, the biggest surprise came from Ducati, pioneers of the modern generation of winglets, and the most vocal opponents of the ban. The Italian squad, revealed under-chief Paolo Ciabatti rather crustily, was going to stick with the standard fairing, unadorned with winglets within or without.

This makes Ducati almost unique, by this time, all the others had revealed their loophole specials. All except newbies KTM, with other things to worry about first. Although the rule allowing one fairing upgrade per season gives Ducati the chance of an about-face.

Loopholes they were, almost literally so. Except that all of them had winglets inside.

Yamaha came first, with double-sided fairing flanks sandwiching vanes presumably angled to return at least a modicum of the downforce that they were obliged to give away, by deleting their large droopy soup-trays of last year.

Suzuki and Aprilia were not far behind, each positioning their own down-force ducts rather higher, on the handlebar shields. Slitty intakes, staggered outlets, and a whole new styling element.

And this last might be the most important aspect, considering that back when wings first started to become more widely used a season and a bit ago, many riders were dubious about what effect they actually had. Can these concealed aerodynamic add-ons be that much different?

The rules are clear. Anything that sticks out of the fairing is now out of the question. Putting the wings inside ducts solves that, while it is also possibly that ducting the airflow might add to their efficacy. Nor need they have been shortened, because rules on the overall width of fairings remain as before.

Six-hundred millimeters to be precise. And handlebars can be no narrower than 450mm across, giving little room to play with.

The more you look at them, the more restrictive the regs appear. It is no wonder that racing fairings look more or less the same. This is not because the traditional “dolphin” design is the best there can be, but because every dimension is defined and limited.

Windscreens can be no wider than 300mm. The fairing nose can project no further forward than 150mm beyond a vertical line from the front wheel spindle. No bodywork may extend beyond the rear wheel.

Front mudguard dimensions likewise draw the strictest parameters. The whole of the front wheel rim must be visible, save where it is necessarily obscured by forks, mudguard mounting struts and braking appendages. The front of the ’guard can extend only to 45 degrees ahead of the spindle; the rear can be level with it.

Intriguingly, “removable air intakes” are excepted from these rules, seeming to give designers the freedom to slam some disguised protruding wings back on. But at the same time the Technical Director has the final say, and is unlikely to let anyone get away with it.

Given the modern refinements triggered by the decision to ban Ducati’s winglets, these basic rules date back to the second decade of world championship racing, which began in 1949. They were formulated in response to a growing fashion for experiments that included the so-called “proboscis” Norton, with an inelegant lengthy snoot, and the fully enclosed “kneeler” from the same firm, and culminated in a growing number of fully enclosing “dustbin” fairings of highly variable quality and efficacy. The best, like Moto-Guzzi’s, were scientifically developed in wind tunnels. The worst were flimsy and scary.

Their banning back then was a far bigger backward step for motorcycle aerodynamics than this year’s banning of wings, stopping worthwhile aerodynamic improvements on the track, and as a result also on the road, where fashion is a more effective marketing tool than engineering, and sporting riders were persuaded that what they really wanted was bikes that looked like grand prix racers.

Probably didn’t take much persuading, to be fair.

The same considerations apply today, which is why the banning of wings, and the resultant new-generation of double-skinned ducted fairings, is likely to lead to the same thing on sporting street bikes sooner rather than later.

And if the ducting does actually work, given that said sports bikes can all too easily reach speeds where aerodynamics become a factor (although not usually within the law), then the banning of wings and their reappearance out of sight will not have been—if you’ll pardon the pun—in vane. CN

Click here for all the latest MotoGP news.