It’s hard to imagine now, but the motorcycles used for off-road racing in America up until the late 1950s, looked an awful lot like the bikes you’d see on the roads every day. There was a good reason for that – they were!

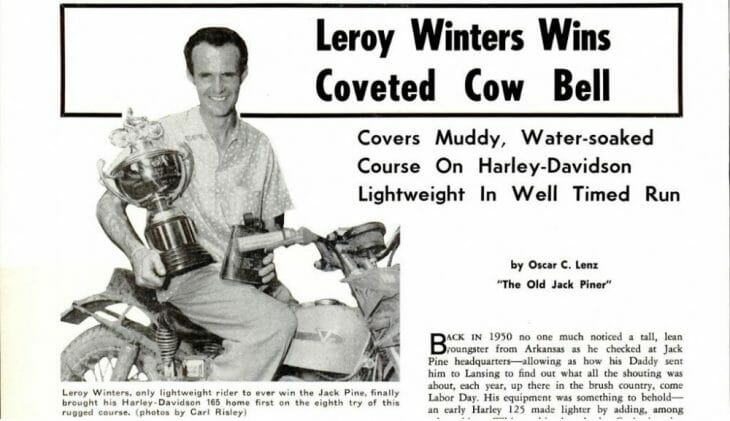

An unlikely victory in the 1956 Jack Pine Enduro by Arkansas rider Leroy Winters began to change all of that.

Remember that prior to 1960s it was practically impossible to buy a purpose-built off-road motorcycle.

The phrase “When men were men” surely must have originated from the days when riders raced full-sized Harley-Davidson and Indian street bikes through the woods. Sure, they would strip the bikes down to bare essentials, but the fact remains these were big, heavy mounts, especially when trying to maneuver through the sandy trails of Michigan in the annual Jack Pine Enduro, the granddaddy of off-road events for much of the first century of American motorcycle racing.

Things began to change in the 1940s when foreign brands, like Triumph, BSA, Matchless, Norton, and Ariel, began to appear at the Jack Pine. But even these bikes were massive by modern-day standards.

Interestingly, in interviewing riders of that distant era, the sheer weight of the big machines used in endure competitions were actually considered advantageous. The idea was that the heavier machines could plow through obstacles like downed branches and mudholes and not get stopped and hung up like lighter weight motorcycles. Not to mention the horsepower advantage.

They even felt the momentum of that weight helped when tackling uphill sections!

I had the opportunity a few years ago, to test those big-bike off-road theories in a way by running a near stock Suzuki DR650 through the single-tracks trails of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Fellow riders were shaking their heads that I would even attempt the trails on the 350-pound machine. I found the bike to be surprisingly good as long as the going wasn’t too technical and it gave me somewhat of a kinship with previous generations of off-roaders, even though in reality the DR is infinitely more capable than a stripped down 1950s Harley 1000cc V-Twin.

I also found out from old-timers that off-roading in the early years often involved teamwork. The bikes of that era had short, soft suspension with little ground clearance, and tended to get hung up on every root or rock they came upon. Unless you were Arnold Schwarzenegger, it meant you would have to wait until nearby fans could come to your aid or another rider came upon the scene to get help lifting a bike that was hung up. Understanding this, you begin to appreciate the cooperative spirit that off-road racing garnered and still remains to this day.

All of those old (and as it turns out largely wrong) ideas about the ideal machine for off-road racing started falling apart with Winters’ run in the 1956 Jack Pine.

It all began for Winters in 1950, when his father told Leroy to head up to Michigan and find out “what all the shouting was about, each year, up there in brush country.” The tall, lean youngster from Fort Smith, Arkansas, undoubtedly turned a lot of heads when he lined up, for the start of that year’s Jack Pine, all legs and arms dangling above a diminutive Harley-Davidson 125cc Model S.

Winters’ bike was the American-made single-cylinder, two-stroke Harley manufactured starting in 1948. These motorcycles were based on the DKW RT125, the drawings for which were taken from Germany as part of war reparations after World War II.

One of the reasons fellow riders might have had a chuckle looking at Winters’ little Harley was the fact that the tiny two-stroke motor produced a grand total of three horsepower! In order to overcome his lack of power, Winters did everything he could to lighten up the 125, including fitting bicycle wheels!

Winters only managed to finish 218 miles of the 500-mile event that first year, but he went back to Arkansas with a good deal of knowledge and went to work improving his bike each year. He returned to the famous race annually and got progressively better. In his fourth attempt, he actually finished the race for the first time. Finally, in 1956, now racing the upsized Harley-Davidson Model 165, and sporting an eye-popping six horsepower, Winters got it right and astounded the experts by taking victory on the diminutive machine.

Rains for weeks ahead of that year’s race made conditions picture-perfect for a small machine, easy to maneuver and lift. Instead of dry, relatively easy to ride trails, riders were greeted with a series of mud bogs and slippery creek crossings. Mud was reported to be waist deep in some places and many of the riders on the traditional Harley and Indians got helplessly stuck. That, combined with the layout men, who’d been criticized for making the course too easy in 1955, designed a much tougher route for ’56. It was said afterwards that no rider made it through the two-day competition without some kind of outside help.

The ’56 victory for Winter’s set off a complete rethinking of off-road machinery. The old ideas of heavier, bigger horsepower began giving way to lighter, easier to handle off-road motorcycles. The Winters win was soon followed up by two Jack Pine victories for John Penton on a small NSU. By the early 1960s the ripple of lightweight machines became a title wave, and the days of lumbering big American V-Twins on the trails were over.

Later in his racing career Winters went on to become an international ambassador for U.S. off-road racing. He competed in the International Six Days Trial from the mid-1960s through 1972. He won a silver medal twice in the World Championship event riding for Team USA.

Winters’ connection to the ISDT was so enduring that in 1995 his club, the Razorback Riders in Arkansas, organized an ISDT reunion ride. Winters died in 1998 and the event was renamed the Leroy Winters Memorial. He was inducted posthumously into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame a year after his passing.

No one knew it at the time, but Winters left a legacy that forever changed the course of off-road motorcycling with his famous Jack Pine victory.